Difference between revisions of "Charles University"

(unstub) |

(alumni) |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

After the 1989-revolution, new purges of staff and libraries began. | After the 1989-revolution, new purges of staff and libraries began. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notable Alumni== | ||

| + | These are only alumni from the Czech periods (1882–1939 and 1945–present) | ||

| + | * [[Václav Bělohradský]] (b. 1944) philosopher | ||

| + | * [[Antonín Holý]] (1936–2012) Czech chemist, played an important role in creating drugs to treat HIV and AIDS | ||

| + | * [[Edvard Beneš]] (1884–1948), sociologist, second president of Czechoslovakia | ||

| + | * [[Adalbert Czerny]] (1863–1941), pediatrician | ||

| + | *[[Rudolf Rabl]] (1889-1951), Czech lawyer | ||

| + | * [[Karel Čapek]] (1890–1938), writer | ||

| + | * [[Eduard Čech]] (1893–1960), mathematician | ||

| + | * [[Stanislav Grof]] (b. 1931), a founder of transpersonal psychology | ||

| + | * [[Jaroslav Heyrovský]] (1890–1967), chemist, [[List of Nobel laureates|Nobel laureate]] | ||

| + | * [[Václav Hlavatý]] (1894–1969), Czech-American mathematician | ||

| + | * [[Miroslav Holub]] (1923–1998), writer and immunologist | ||

| + | * [[Milada Horáková]] (1901-1950], [[women's rights]] activist, politician, [[Resistance_movement#Freedom_fighter|freedom-fighter]] against [[Nazis]] and [[communists]] | ||

| + | * [[Bohumil Hrabal]] (1914–1997), writer | ||

| + | * [[Jan Janský]] (1873–1921), discoverer of blood types | ||

| + | * [[Charles I of Austria]] (1887–1922), last emperor of Austria, last king of Bohemia (Czech & German universities) | ||

| + | * [[Jan Kavan]] (b. 1946), politician and diplomat | ||

| + | * [[Luboš Kohoutek]] (b. 1935), astronomer | ||

| + | * [[Henry Kučera]] (b. 1925), linguist/cognitive scientist | ||

| + | * [[Martin Kukučín]] (1860–1928), [[Slovakia|Slovak]] writer | ||

| + | * [[Milan Kundera]] (b. 1929), writer | ||

| + | * [[Lyubomir Miletich]] (1863–1937), Bulgarian academician | ||

| + | * [[George Placzek]] (1905–1955), physicist | ||

| + | * [[Jan Stráský]] (b. 1940), politician | ||

| + | * [[Ota Šik]] (1919–2004), economist | ||

| + | * [[Vavro Šrobár]] (1867–1950), Slovak physician and politician | ||

| + | * [[Peter Tomka]] (b. 1956), International Court of Justice judge | ||

| + | * [[Ivana Trump]] (b. 1949), Socialite and entrepreneur | ||

| + | * [[Vladislav Vančura]] (1891–1942), writer | ||

| + | * [[Michał Vituška]] (1907–1945), Belarusian leader of the ''[[Belarusian Black Cats|Black Cats]]'' | ||

| + | * [[Wilhelm Winkler]] (1884–1984), statistician | ||

| + | * [[David Navara]] (b. 1985), chess grandmaster | ||

{{SMWDocs}} | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:48, 5 February 2021

(University) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Formation | 1348 |

| Type | Public |

| One of the top universities in Eastern Europe | |

Charles University, known also as Charles University in Prague (Czech: Univerzita Karlova; German: Karls-Universität) or historically as the University of Prague, is the oldest and largest university in the Czech Republic.[1] It is one of the oldest universities in Europe in continuous operation.[2] Today, the university consists of 17 faculties located in Prague, Hradec Králové and Pilsen. The Charles University belongs to the top three universities in Central and Eastern Europe.[3] It is ranked around 200-300 in the world.[4][5]

Contents

History

Medieval university (1349–1419)

The establishment of a medieval university in Prague was inspired by Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV.[6] He asked his friend and ally, Pope Clement VI, to do so. On 26 January 1347 the pope issued the bull establishing a university in Prague, modeled on the University of Paris, with the full (4) number of faculties, that is including a theological faculty. On 7 April 1348 Charles, the king of Bohemia, gave to the established university privileges and immunities from the secular power in a Golden Bull[7] and on 14 January 1349 he repeated that as the King of the Romans. Most Czech sources since the 19th century—encyclopedias, general histories, materials of the University itself—prefer to give 1348 as the year of the founding of the university, rather than 1347 or 1349. This was caused by an anticlerical shift in the 19th century, shared by both Czechs and Germans.

The university was opened in 1349. The university was sectioned into parts called nations: the Bohemian, Bavarian, Polish and Saxon. The Bohemian natio included Bohemians, Moravians, southern Slavs, and Hungarians; the Bavarian included Austrians, Swabians, natives of Franconia and of the Rhine provinces; the Polish included Silesians, Poles, Ruthenians; the Saxon included inhabitants of the Margravate of Meissen, Thuringia, Upper and Lower Saxony, Denmark, and Sweden. Ethnically Czech students made 16–20% of all students.[8] Archbishop Arnošt of Pardubice took an active part in the foundation by obliging the clergy to contribute and became a chancellor of the university (i.e., director or manager).

The first graduate was promoted in 1359. The lectures were held in the colleges, of which the oldest was named for the king the Carolinum, established in 1366. In 1372 the Faculty of Law became an independent university.[9]

In 1402 Jerome of Prague in Oxford copied out the Dialogus and Trialogus of John Wycliffe. The dean of the philosophical faculty, Jan Hus, translated Trialogus into the Czech language. In 1403 the university forbade its members to follow the teachings of Wycliffe, but his doctrine continued to gain in popularity.

In the Western Schism, the Bohemian natio took the side of king Wenceslaus and supported the Council of Pisa (1409). The other nationes of the university declared their support for the side of Pope Gregory XII, thus the vote was 1:3 against the Bohemians. Hus and other Bohemians, though, took advantage of Wenceslaus' opposition to Gregory. By the Decree of Kutná Hora (German: [Kuttenberg] error: {{lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) on 18 January 1409, the king subverted the university constitution by granting the Bohemian masters three votes. Only a single vote was left for all other three nationes combined, compared to one vote per each natio before. The result of this coup was the emigration of foreign (mostly German) professors and students, founding the University of Leipzig in May 1409. Before that, in 1408, the university had about 200 doctors and magisters, 500 bachelors, and 30,000 students; it now lost a large part of this number, accounts of the loss varying from 5000 to 20,000 including 46 professors. In the autumn of 1409, Hus was elected rector of the now Czech-dominated rump university.

Thus, the Prague university lost the largest part of its students and faculty. From then on the university declined to a merely regional institution with a very low status.[10] Soon, in 1419, the faculties of theology and law disappeared, and only the faculty of arts remained in existence.

Protestant academy (1419–1622)

The faculty of arts became a centre of the Hussite movement, and the chief doctrinal authority of the Utraquists. No degrees were given in the years 1417–30; at times there were only eight or nine professors. Emperor Sigismund, son of Charles IV, took what was left into his personal property and some progress was made. The emperor Ferdinand I called the Jesuits to Prague and in 1562 they opened an academy—the Clementinum. From 1541 till 1558 the Czech humanist Template:Ill (1516–1566) was a professor of Greek language.[11] Some progress was made again when the emperor Rudolph II took up residence in Prague. In 1609 the obligatory celibacy of the professors was abolished.[12] In 1616 the Jesuit Academy became a university. (It could award academic degrees.)

Jesuits were expelled 1618–1621 during the early stages of the Thirty Years' War, which was started in Prague by anti-Catholic and anti-Imperial Bohemians. By 1622 the Jesuits had a predominant influence over the emperor. An Imperial decree of 19 September 1622 gave the Jesuits supreme control over the entire school system of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. The last four professors at the Carolinum resigned and all of the Carolinum and nine colleges went to the Jesuits. The right of handing out degrees, of holding chancellorships and of appointing the secular professors was also granted to the Jesuits.

Charles-Ferdinand University (1622–1882)

Cardinal Ernst Adalbert von Harrach actively opposed union of the university with another institution and the withdrawal of the archepiscopal right to the chancellorship and prevented the drawing up of the Golden Bull for the confirmation of the grant to Jesuits. Cardinal Ernst funded the Collegium Adalbertinum and in 1638 emperor Ferdinand III limited the teaching monopoly enjoyed by the Jesuits. He took from them the rights, properties and archives of the Carolinum making the university once more independent under an imperial protector. During the last years of the Thirty Years' War the Charles Bridge in Prague was courageously defended by students of the Carolinum and Clementinum. Since 1650 those who received any degrees took an oath to maintain the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin, renewed annually.

On 23 February 1654 emperor Ferdinand III merged Carolinum and Clementinum and created a single university with four faculties—Charles-Ferdinand University.[13] Carolinum had at that time only the faculty of arts, as the only faculty surviving the period of the Hussite Wars. Starting at this time, the university designated itself Charles-Ferdinand University (Universitatis Carolinae Ferdinandeae). The dilapidated Carolinum was rebuilt in 1718 at the expense of the state.

The rebuilding and the bureaucratic reforms of universities in the Habsburg monarchy in 1752 and 1754 deprived the university of many of its former privileges. In 1757 a Dominican and an Augustinian were appointed to give theological instruction. However, there was a gradual introduction of enlightened reforms, and this process culminated at the end of the century when even non-Catholics were granted the right to study. On 29 July 1784, German replaced Latin as the language of instruction.[14] For the first time Protestants were allowed, and soon after Jews. The university acknowledged the need for a Czech language and literature chair. Emperor Leopold II established it by a courtly decree on 28 October 1791. On 15 May 1792, scholar and historian Template:Ill[15] was named the professor of the chair. He started his lectures on 13 March 1793.[16]

In the revolution of 1848, German and Czech students fought for the addition of the Czech language at the Charles-Ferdinand University as a language of lectures. Due to the demographic changes of the 19th century, Prague ceased to have a German-language majority around 1860. By 1863, 22 lecture courses were held in Czech, the remainder (out of 187) in German. In 1864, Germans suggested the creation of a separate Czech university. Czech professors rejected this because they did not wish to lose the continuity of university traditions.

Split into Czech and German universities

It soon became clear that neither the German-speaking Bohemians nor the Czechs were satisfied with the bilingual arrangement that the University arranged after the revolutions of 1848. The Czechs also refused to support the idea of the reinstitution of the 1349 student nations, instead declaring their support for the idea of keeping the university together, but dividing it into separate colleges, one German and one Czech. This would allow both Germans and Czechs to retain the collective traditions of the University. German-speakers, however, quickly vetoed this proposal, preferring a pure German university: they proposed to split Charles-Ferdinand University into two separate institutions.

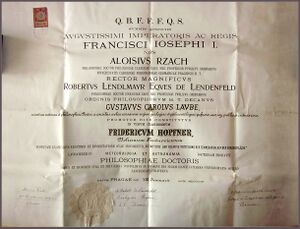

After long negotiations, Charles-Ferdinand was divided into a German Charles-Ferdinand University (Deutsche Karl-Ferdinands-Universität) and a Czech Charles-Ferdinand University (Česká universita Karlo-Ferdinandova) by an act of the Cisleithanian Imperial Council, which Emperor Franz Joseph sanctioned on 28 February 1882.[17] Each section was entirely independent of the other, and enjoyed equal status. The two universities shared medical and scientific institutes, the old insignia, aula, library, and botanical garden, but common facilities were administrated by the German University. The first rector of the Czech University became Template:Ill.

In 1890, the Royal and Imperial Czech Charles Ferdinand University had 112 teachers and 2,191 students and the Royal and Imperial German Charles Ferdinand University had 146 teachers and 1,483 students. Both universities had three faculties; the Theological Faculty remained the common until 1891, when it was divided as well. In the winter semester of 1909–10 the German Charles-Ferdinand University had 1,778 students; these were divided into: 58 theological students, for both the secular priesthood and religious orders; 755 law students; 376 medical; 589 philosophical. Among the students were about 80 women. The professors were divided as follows: theology, 7 regular professors, 1 assistant professor, 1 docent; law, 12 regular professors, 2 assistant professors, 4 docents; medicine, 15 regular professors, 19 assistant, 30 docents; philosophy, 30 regular professors, 8 assistant, 19 docents, 7 lecturers. The Czech Charles-Ferdinand University in the winter semester of 1909–10 included 4,319 students; of these 131 were theological students belonging both to the secular and regular clergy; 1,962 law students; 687 medical; 1,539 philosophical; 256 students were women. The professors were divided as follows: theological faculty, 8 regular professors, 2 docents; law, 12 regular, 7 assistant professors, 12 docents; medicine, 16 regular professors, 22 assistant, 24 docents; philosophy, 29 regular, 16 assistant, 35 docents, 11 lecturers.

The high point of the German University was the era preceding the First World War, when it was home to world-renowned scientists such as physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach, Moritz Winternitz and Albert Einstein. In addition, the German-language students included prominent individuals such as future writers Max Brod, Franz Kafka, and Johannes Urzidil.[18] The "Lese- und Redehalle der deutschen Studenten in Prag" ("Reading and Lecture Hall of the German students in Prague"), founded in 1848, was an important social and scientific centre. Their library contained in 1885 more than 23,519 books and offered 248 scientific journals, 19 daily newspapers, 49 periodicals and 34 papers of entertainment. Regular lectures were held to scientific and political themes.

Even before the Austro-Hungarian Empire was abolished in late 1918, to be succeeded by Czechoslovakia, Czech politicians demanded that the insignia of 1348 were exclusively to be kept by the Czech university. The Act No. 197/1919 Sb. z. a n. established the Protestant Theological Faculty, but not as a part of the Charles University.[19] (That changed on 10 May 1990, when it finally became a faculty of the university.[20])

In 1920, the so-called Lex Mareš (No. 135/1920 Sb. z. a n.) was issued, named for its initiator, professor of physiology František Mareš, which determined that the Czech university was to be the successor to the original university.[21] Dropping the Habsburg name Ferdinand, it designated itself Charles University, while the German university was not named in the document, and then became officially called the German University in Prague (Deutsche Universität Prag).[22][23]

In 1921 the German-speaking Bohemians considered moving[24] their university to Liberec (Reichenberg), in northern Bohemia. In 1930, about 42,000 inhabitants of Prague spoke German as their native language, while millions lived in northern, southern and western Bohemia, in Czech Silesia and parts of Moravia near the borders with Austria and Germany.

In October 1932, after Naegle's death, the Czechs started again a controversy over the insignia. Ethnic tensions intensified, although some professors of the German University were members of the Czechoslovak government. Any agreement to use the insignia for both the universities was rejected. On 21 November 1934, the German University had to hand over the insigniae to the Czechs. The German University senate sent a delegation to Minister of Education Krčmář to protest the writ. At noon on 24 November 1934, several thousand students of the Czech University protested in front of the German university building. The Czech rector Karel Domin gave a speech urging the crowd to attack, while the outnumbered German students tried to resist. Under the threat of violence, on 25 November 1934 rector Template:Ill (1873–1951) handed over the insigniae. These troubles of 1934 harmed relations between the two universities and nationalities.

The tide turned in 1938 when, following the Munich Agreement, German troops entered the border areas of Czechoslovakia (the so-called Sudetenland), as did Polish and Hungarian troops elsewhere. On 15 March 1939 Germans forced Czecho-Slovakia to split apart and the Czech lands were occupied by Nazis as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Reichsprotektor Konstantin von Neurath handed the historical insigniae to the German University, which was officially renamed Deutsche Karls-Universität in Prag. On 1 September 1939 the German University was subordinated to the Reich Ministry of Education in Berlin and on 4 November 1939 it was proclaimed to be Reichsuniversität.

On 28 October 1939, during a demonstration, Jan Opletal was shot. His burial on 15 November 1939 became another demonstration.[25] On 17 November 1939 (now marked as International Students' Day) the Czech University and all other Czech institutions of higher learning were closed, remaining closed until the end of the War. Nine student leaders were executed and about 1,200 Czech students were interned in Sachsenhausen and not released until 1943. About 20 or 35 interned students died in the camp. On 8 May 1940 the Czech University was officially renamed Czech Charles University (Česká universita Karlova) by government regulation 188/1940 Coll.

World War II marks the end of the coexistence of the two universities in Prague.

Present-day university (since 1945)

Although the university began to recover rapidly after 1945, it did not enjoy academic freedom for long. After the communist coup in 1948, the new regime started to arrange purges and repress all forms of disagreement with the official ideology, and continued to do so for the next four decades, with the second wave of purges during the "normalization" period in the beginning of the 1970s.[26] Only in the late 1980s did the situation start to improve; students organized various activities and several peaceful demonstrations in the wake of the Revolutions of 1989 abroad.[27] This initiated the "Velvet Revolution" in 1989, in which both students and faculty of the university played a large role. Václav Havel, a writer, dramatist and philosopher, was recruited from the independent academic community and appointed president of the republic in December 1989.

After the 1989-revolution, new purges of staff and libraries began.

Notable Alumni

These are only alumni from the Czech periods (1882–1939 and 1945–present)

- Václav Bělohradský (b. 1944) philosopher

- Antonín Holý (1936–2012) Czech chemist, played an important role in creating drugs to treat HIV and AIDS

- Edvard Beneš (1884–1948), sociologist, second president of Czechoslovakia

- Adalbert Czerny (1863–1941), pediatrician

- Rudolf Rabl (1889-1951), Czech lawyer

- Karel Čapek (1890–1938), writer

- Eduard Čech (1893–1960), mathematician

- Stanislav Grof (b. 1931), a founder of transpersonal psychology

- Jaroslav Heyrovský (1890–1967), chemist, Nobel laureate

- Václav Hlavatý (1894–1969), Czech-American mathematician

- Miroslav Holub (1923–1998), writer and immunologist

- Milada Horáková (1901-1950], women's rights activist, politician, freedom-fighter against Nazis and communists

- Bohumil Hrabal (1914–1997), writer

- Jan Janský (1873–1921), discoverer of blood types

- Charles I of Austria (1887–1922), last emperor of Austria, last king of Bohemia (Czech & German universities)

- Jan Kavan (b. 1946), politician and diplomat

- Luboš Kohoutek (b. 1935), astronomer

- Henry Kučera (b. 1925), linguist/cognitive scientist

- Martin Kukučín (1860–1928), Slovak writer

- Milan Kundera (b. 1929), writer

- Lyubomir Miletich (1863–1937), Bulgarian academician

- George Placzek (1905–1955), physicist

- Jan Stráský (b. 1940), politician

- Ota Šik (1919–2004), economist

- Vavro Šrobár (1867–1950), Slovak physician and politician

- Peter Tomka (b. 1956), International Court of Justice judge

- Ivana Trump (b. 1949), Socialite and entrepreneur

- Vladislav Vančura (1891–1942), writer

- Michał Vituška (1907–1945), Belarusian leader of the Black Cats

- Wilhelm Winkler (1884–1984), statistician

- David Navara (b. 1985), chess grandmaster

Alumni on Wikispooks

| Person | Born | Died | Nationality | Summary | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edvard Beneš | 28 May 1884 | 3 September 1948 | Czechoslovakia | Politician | |

| Věra Jourová | 18 August 1964 | Politician Lawyer Teacher Deep state functionary Businessperson | Promoting "freedom of expression and information" by pushing internet censorship | ||

| Franz Kafka | 3 July 1883 | 3 June 1924 | Author | “Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested.” ― Franz Kafka, The Trial | |

| Josef Korbel | 20 September 1909 | 18 July 1977 | US | Diplomat Academic Deep state operative | Spooky Czechoslovak-US professor in international politics. His daughter Madeleine Albright was US Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton, and he was the mentor of George W. Bush's Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice. |

| Faisal Mekdad | 1954 | ||||

| Jiří Pehe | 26 August 1955 | Czech Republic | Author | Czech presidential advisor who attended the 2001 Bilderberg. Formerly worked for Freedom House and Radio Free Europe. | |

| Tomáš Pojar | 28 December 1973 | Czech Republic | Diplomat "Terror expert" | Czech "terror expert" and Czech Ambassador to Israel 2010-2014 | |

| Ivana Trump | 20 February 1949 | 14 July 2022 | Czech Republic US | Model Fixer? | First wife of Donald Trump, mentioned in relation to Ghislaine Maxwell, died a suspicious death in July 2022 |

| Michael Zantovsky | 3 January 1949 | Czech Republic | Author Diplomat Politician Psychologist | Bilderberger Czech diplomat |

References

- ↑ Joachim W. Stieber: "Pope Eugenius IV, the Council of Basel and the secular and ecclesiastical authorities in the Empire: the conflict over supreme authority and power in the church", Studies in the history of Christian thought, Vol. 13, Brill, 1978, ISBN 90-04-05240-2, p.82; Gustav Stolper: "German Realities", Read Books, 2007, ISBN 1-4067-0839-9, p. 228; George Henry Danton: "Germany ten years after", Ayer Publishing, 1928, ISBN 0-8369-5693-1, p. 210; Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius: "The German Myth of the East: 1800 to the Present", Oxford Studies in Modern European History Series, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 0-19-954631-2, p. 109; Levi Seeley: "History of Education", BiblioBazaar, ISBN 1-103-39196-8, p. 141

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20150710010658/http://www.degreelibrary.org/30-of-the-oldest-universities-in-the-world/

- ↑ http://www.iu.qs.com/2011/09/eastern-europe-and-central-asia-in-the-2011-qs-world-university-rankings/

- ↑ http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2018.html

- ↑ https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2019 | title=QS World University Rankings 2019

- ↑ Charles was since 11 July 1346 antiking of Romans, since 26 August 1346 king of Bohemia, since 17 June 1349 lawful king of Romans as Charles IV and from 5 April 1355 Holy Roman Emperor.

- ↑ http://www.cuni.cz/UK-145.html

- ↑ http://www.cs-magazin.com/2005-03/view.php?article=articles/cs050334.htm

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=EEABAAAAYAAJ&printsec=titlepage

- ↑ Lexikon des Mittelalters: "Prag. Universität", J.B. Metzler, Vol. 7, cols 163–164

- ↑ http://libri.cz/databaze/kdo18/search.php?zp=6&name=KOL%CDN

- ↑ http://www.cuni.cz/UKENG-3.html

- ↑ http://libri.cz/databaze/dejiny/text/t45.html

- ↑ {http://www.cuni.cz/UK-1584-version1-history_of_UK.doc

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20120205030917/http://www.ujc.cas.cz/lingviste/pelcl-frantisek.html

- ↑ http://libri.cz/databaze/dejiny/text/t57.html |

- ↑ http://libri.cz/databaze/dejiny/text/t73.html

- ↑ http://www.johannes-urzidil.cz/zivot.html

- ↑ http://psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/stenprot/043schuz/s043002.htm

- ↑ http://web.etf.cuni.cz/ETFENG-24.html

- ↑ http://psp.cz/eknih/1918ns/ps/stenprot/105schuz/s105003.htm

- ↑ http://is.cuni.cz/webapps/archiv/public/books/bs/1201577654060565/?lang=en

- ↑ http://www.cuni.cz/UKEN-106.html%7Cwebsite=www.cuni.cz

- ↑ https://archive.today/20120719020502/http://senat.cz/zajimavosti/tisky/1vo/tisky/T1174_00.htm

- ↑ http://www.libri.cz/databaze/dejiny/

- ↑ http://www.cuni.cz/UKENG-181.html

- ↑ http://www.prague-life.com/prague/charles-university |title=A University Fit for a King |publisher=Prague-life.com