Marina de Larracoechea

| |

| Born | September 1947 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Interests | |

Marina appealed to the five Scottish judges to conduct an independent review of the evidence on the grounds that the full truth behind the Lockerbie bombing had been deliberately withheld. They rejected this request. She applied for permission to intervene and ask questions during the hearing of Megrahi’s appeal. They rejected this application. | |

Marina de Larracoechea is a former interior designer from Spain. After her younger sister, air stewardess Nieves de Larracoechea, was killed in the explosion of Pan Am Flight 103 above Lockerbie, Marina de Larracoechea has energetically sought to uncover the truth about the Lockerbie bombing. She has appeared on commercially-controlled media including NBC.[1]

In June 1990, Marina de Larracoechea visited Lockerbie campaigner Patrick Haseldine at the Clock Tower Café in Ongar to discuss the letter "Finger of suspicion" he had sent to The Guardian six months previously, suggesting police inquiries into Lockerbie had been subject to political interference.[2]

Contents

Lockerbie FAI

Marina de Larracoechea and her brother-in-law Frank Rozenkranz attended the Lockerbie Fatal Accident Inquiry held in Dumfries from October 1990 to February 1991 into the deaths of the 259 people aboard the Boeing 747 and 11 people on the ground in Lockerbie, Scotland.

Designated as 'official representatives' – the only lay people given permission to cross-examine witnesses – they were seated next to the British and American lawyers representing other victims' relatives and chose to be involved in the case because:

- "We want issues raised in our own way — not the way a lawyer would deal with them," de Larracoechea said. "We believe the disaster was preventable. There were advance warnings which were specific enough for the U.S. government to advise diplomats not to travel on the flight. Yet they were not made public. Not even the crew of the aircraft was told. We want to know why.'

- "My sister, 18 months my junior, was the purest, most beautiful person. She was murdered along with 269 other innocent people. They paid with their lives for errors of one administration or another. Those responsible should be in jail. And I don't just mean the terrorists. I include the passive accomplices — the people who did not pass on the warnings: the State Department; the counter-intelligence agents; the Pan Am sales managers."[3]

Cross-examination

Cross-examining Pan Am baggage handlers during the FAI, Marina de Larracoechea asked Amarjit Singh Sidhu, 41, if he knew of at least three security breaches at Heathrow staged after the disaster, and that journalists had created fake identity cards to enter the forbidden area. But Sheriff Principal John Mowat, the presiding judge, overruled the question, saying: "I'm not concerned with Heathrow after the disaster and what precautions were taken there. My concern is with what led up to the disaster."

She wanted to establish whether Pan Am employees would have recognised an intruder:

- "I don't know how they could control it if anyone was really set on a bomb attempt ... they would get through quite easily, I believe, because of lack of control."

She asked Sidhu if he recognised new workers by their badges or their uniform. The Pan Am employee said this was a task mainly for security officers, but all employees had been briefed to check on anybody they did not recognise.

Sidhu said loaders on duty for Flight 103 would have known if a stranger or an imposter had been part of the group that loaded container 4041, which contained the suitcase in which had been hidden the radio bomb that killed all 259 occupants and 11 residents of the Scottish town of Lockerbie.

He and two other handlers said they had seen no irregularities or any strangers during the unloading of cargo from a connecting Frankfurt flight. Terence Crabtree, 42, said container 4041 had about six or seven suitcases from different airlines. He said when it was full, he locked it and drove it to the awaiting Boeing 747.[4]

Questioned by Marina de Larracoechea, Pan Am's director of flight services at Heathrow, Michael Sullivan, revealed to the FAI that the normal cabin crew for a Boeing 747 was 13. But because of the passenger load on Flight 103, the correct number should have been 12. Asked why there had been 13 he replied:

- "I cannot definitely say the reason. When we looked at the list afterwards we found there was a 13th. The only persons who would have known (the reason for the extra member) were the crew", Sullivan said.

Asked if he was saying an extra flight person "could just walk in", he answered:

- "It is the responsibility of the purser, who has the crew list, to advise us of any crew difference."

Larracoechea then asked him if it was possible that an extra person could appear at the airport and after an exchange of words, without anyone else knowing, join the flight crew:

- "It should not happen but it appears to have happened in this case. I didn't know who to talk to. The only person who would have known would have been the purser who wrote the 13th name on the assignment sheet which the 13th person had signed", Sullivan said.

Asked by reporters after the hearing if he could name the 13th cabin crew member, Sullivan said: "I am not going to talk about that."

"I think I know who it was but I am not certain. I do not want to give any name at this stage", Larracoechea said.

The FAI, which had run for 10 weeks and heard a total of 46 days evidence from about 150 witnesses by 7 December 1990, was due to resume on 22 January 1991. The estimated cost of staging it is three million pounds, or about $5.8 million.[5]

Extract of FAI report

Page 12/13 of the FAI report states:

Ms Larracoechea, appearing for her brother-in-law who is the husband of one of the crew members who died in the disaster, said that she accepted the submissions made in the areas which had been addressed. Her concern was with other areas. She suggested that for the future, planners for emergencies should aim to treat each relative as an individual and have regard to their personal needs in relation to

- (a) viewing the body;

- (b) the exact location where the body was found; and,

- (c) the personal property of the victim.

She then suggested that where there was a general threat it was not possible to anticipate how a bomb might be placed aboard an aircraft. Security should have been stepped up in all areas. All warnings, however improbable, should be treated seriously. She submitted that in the case of a threat as specific as the Helsinki warning, Pan American had an obligation to inform the public and its employees.

She submitted that the evidence disclosed a failure to enforce their own regulations by the regulatory authorities. Airlines had been left to monitor their own performance. She criticised the Department of Transport for lack of co-ordination, a relaxed attitude, a poor reaction to warnings, and a failure to respond to the suggestions of the Select Committee of the House of Commons. She suggested that there should be an independent agency for aviation security with the public sector involved in development and research and supported Dr Swire’s submission as to the technology which was available in December 1988 and the need for Government funding and direction of research. Regulations should set the standards for technology.

She was not prepared to accept the evidence as to where and how the bomb had been placed in the aircraft and submitted that it could have been substituted in the container when it was in the baggage build-up area. If so, it was necessary to look more closely at the role of Heathrow Airport.

Finally, she submitted that the Inquiry had been too limited in its consideration of

- (1) The role of international intelligence and its attitude in countering terrorism;

- (2) The assessment of the Helsinki threat;

- (3) The publication of threats to a privileged few; and,

- (4) The extent, if any, to which Pan American’s bookings had been affected by publication of the Helsinki threat in the US Embassy at Moscow. There should be a further judicial inquiry into these matters.[6]

FAI recollections

In June 2012, editor of the Scottish Review, Kenneth Roy, recalled what had happened 22 years earlier:

In December 1990, close to the week of Lockerbie's second anniversary, I turned up one morning at a psychiatric hospital in Dumfries. Part of the grounds had been converted into a mini-village, with its own 400-seat auditorium, administrative block, media centre and restaurant. I reported to the media centre and was issued with a badge, a desk and a telephone. "Where is everybody?", I asked. There was no one in this centre; only rows and rows of empty desks and a long corridor of empty cubicles, each reserved for some famous newspaper or broadcasting organisation. "Oh, there’s never anybody here", the security man replied casually. "We haven’t bothered to connect most of the phones." He suggested that I should put my feet up, have a smoke, and listen to an audio feed of the proceedings. It was, he assured me, warmer in here than in the room with the 400-seat auditorium.

I went to the room anyway. I was frisked at the door, emerging through a metal archway into a large, gloomy hall with a stage and municipal-green curtains, tightly drawn to exclude the little natural light. A third of the floor space had been penned off for bewigged counsel and their assistants – 28 of them. A team of three shorthand writers worked in 15-minute rotas. On the stage sat the impassive sheriff who was hearing the evidence. In the press benches, a handful of reporters.

But the auditorium was deserted. Not one of the 400 seats in the public benches was occupied. During a break I asked an official if this was unusual. He told me that the highest attendance had been 10, on one of the early days. There had been no one for weeks.

This was the Fatal Accident Inquiry into Britain’s worst peacetime atrocity, a terrorist crime which claimed 270 lives.

Only one person in this oppressively dim room was of more than passing interest. She sat incongruously in the pen reserved for the lawyers, but it was clear that she was not one of that lot. She was a woman in early middle age, beautiful, stylishly dressed. I observed that her concentration never wavered and that she never stopped writing; writing; writing.

I discovered that her name was Marina de Larracoechea, that she was Spanish, an interior designer, that her sister Nieves, had been a flight attendant on Pan Am Flight 103, and that she was here to represent her murdered sister. Legal representation did not interest Marina. She had to be in this unfamiliar town in person, in the depth of winter, resting her head heaven knows where, week after week, listening, writing, head down, writing.

The airline’s head of security – even for him there was no audience – gave evidence. I remember 22 years later that he spoke of ‘bouncing off the walls in frustration’ at his employer’s lack of interest in his plans to improve the inadequate security. We did not know then about the Heathrow possibility. We knew very little. Megrahi was a free man. Tony Gauci was an obscure Maltese shopkeeper. Peter Fraser was just another of those jolly affable chaps at the Scottish bar, no one suspecting that he thought in such sophisticated imagery as a witness being an apple short of a picnic.

It was an inquiry taking place in the dark. Almost literally.

As she listened to the security man’s evidence, Marina stepped up the pace of her ferocious note-taking. I didn’t appreciate at the time the nature of this phenomenon; it took a while for my slow head to work it out. It was someone bearing witness. I hadn’t seen the like of it before and I haven’t seen the like of it since. It was a deeply impressive spectacle.

At every new turn in the Lockerbie saga, I wondered what had happened to Marina. Maybe it was all that bar-room philosophy – to say nothing of all that speaking for Scotland crap – which finally drove me to make inquiries. It seems she is still alive and living in New York:

- "I don’t care about work any more", she said some years ago. "I can’t do it any more. Personally I don’t think I will ever be able to get back to many things in my life. All the rest is very minor compared to the fact that she is not around any more."

Marina rejected a £4m payoff offered to each of the families. She said the money meant nothing to her and that all she wanted was the truth.

Marina requested that Nieves’ name should be excluded from the Lockerbie memorial because neither truth nor justice had prevailed. I don’t know whether this request was respected.

Marina attended part of the trial in the Netherlands and left it convinced of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi’s innocence. She said at the time of his detention in Scotland:

- "The fact that he is languishing in a Scottish prison is a source of great sadness to me and to many other relatives I have spoken to. He is nothing more than a scapegoat."

Marina appealed to the Scottish judges to conduct an independent review of the evidence on the grounds that the full truth behind the bombing had been deliberately withheld. They rejected this request. She applied for permission to intervene and ask questions during the hearing of Megrahi’s appeal. They rejected this application.

The most recent reference I have been able to source appeared in a Spanish newspaper at the beginning of last year. It was in the form of a personal statement.

Marina said:

- "I have worked hard with dedication and sacrifice, especially for truth and justice, in the case of the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 where my sister Nieves was murdered, along with 269 other equally precious and irreplaceable lives. This carnage, politically induced, announced and expected, occurred on 21 December 1988 over Lockerbie, Scotland. Others, mainly government officials, diplomats and big businessmen had precise prior knowledge that helped them to change their flights and save their lives. Silence reigns over this and other important aspects."

In the same statement, Marina pleaded for health to continue fighting with even more determination "and a little good fortune to help us bear with dignity the enormous burden of these 22 years."

Her dignity was never in doubt. I experienced it for myself that long-ago December day in the tightly-curtained room. I’m reading it again through the lines I’ve just quoted.

For 270 of those 400 vacant seats there was a victim. Yet it seems that the powerful have won. The powerful have kept their secrets. The powerful have always depended on the emptiness of the auditorium.[7]

Marina rebuffed

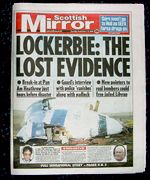

Ten years after the Fatal Accident Inquiry, at a preliminary appeal hearing held at the Scottish Court in the Netherlands (Camp Zeist) in October 2001, Marina de Larracoechea told the five Scottish judges (Lords Cullen, Kirkwood, MacFadyen, Nimmo-Smith and McEwan) that the human rights of the victims' families had been violated because the prosecutor in the Lockerbie bombing case, Scotland's Lord Advocate Colin Boyd, was a political appointee. She called for an independent review of the evidence gathered in the case and said the appeal court should hear evidence which was not brought before the original trial. In particular, security guard Ray Manly's evidence about a break-in at Heathrow's Pan Am baggage area in the early hours of 21 December 1988, which was first published in the Daily Mirror of 11 September 2001.[8] This, she said, would address the issues of who planned the atrocity and who was responsible for allowing the suitcase containing the bomb to be smuggled on board the doomed aircraft.

Marina de Larracoechea told the court that the Crown's case needed further scrutiny because the full truth behind the bombing had not come out during the Lockerbie trial. She told the five judges that "key and central aspects of the case were repeatedly shielded" during the Fatal Accident Inquiry into the disaster for fear of prejudicing future criminal proceedings and on the understanding that these would be fully addressed at the trial.

However, she said many issues remained unaddressed and could only be dealt with through an independent review of all evidence. She said:

- "My view is that what is necessary is an independent review of everything that came out in the original criminal investigation - that's the first step and then depending on what's found it may be necessary to proceed further. I only seek the truth and justice of the case as soon as possible like most of the relatives."

Similar calls for an independent review have been made by other relatives of victims. Families recently renewed their calls for a full independent inquiry into the disaster during a meeting with Foreign Secretary Jack Straw. In particular they want the failure of the intelligence services and airport and airline authorities to stop the bomb getting on board to be scrutinised. Some other relatives of those killed, including Dr Jim Swire and the Rev John Mosey, who both lost daughters, travelled to Holland for the hearing.

In rejecting her request, Lord Cullen, the presiding judge, said the role of the court was simply to hear the appeal of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the man convicted of the Lockerbie bombing.[9]

Chief defence lawyer Bill Taylor told the court his team would review any new material provided. The appeal came at a time when the world was again tackling the problem of capturing terrorists and bringing them to justice in response to the September 11 attacks in the United States.[10]

Political interference

Speaking to BBC Scotland in October 2001, Marina de Larracoechea said she was not satisfied with either al-Megrahi's conviction or the evidence which was heard in court:

- "I didn't see enough in the trial to convince me that he did it, but I think the defence should have gone further in making the case. But, as I said, what I saw didn't convince me.

She believed there has effectively been a cover-up over the bombing by various intelligence agencies, saying:

- "It's just not convenient to look into what really happened. I think the main problems for us, for the victims and us the relatives, is the relevant intelligence gathered prior, the credibility and the specificity of this intelligence, the fact that it was evaluated seriously, that it was used to benefit and save the lives of government employees and yet these agencies, who have the duty to gather intelligence and act upon it, the duty to care, they didn't do anything for the public and I think that is where the real responsibilities lie."

Asked whether there should be a public inquiry in an effort to draw out that intelligence, she said:

- "I had hoped that we could have done much faster than really, considering the absurdity of going into a public inquiry 15 years after where we'll probably all be ga-ga if we are still alive and the chances of getting to any fresh or important evidence has been taken care of a long time ago. I mean the essence of a good investigation is that you get your hands on it as soon as possible. Not 15 years after, 15 years after in this process with the most colossal investigation of the 20th century is a victimisation of the relatives of the victims. We are victims of the way this case is being handled."

Marina de Larracoechea said she believed there had been widespread political interference in the case from the outset:

- "In an international, geopolitical situation with many agendas and it changes, it varies. But at the corner of the Pan Am Flight 103 I think there is no doubt that there is the United States, England and Germany."

Despite her reservations about the way the case has been handled, she remains determined to see justice done:

- "We'll keep trying that is all I can say, but I think this is an unduly lengthy process of getting to the truth. I mean, 13 years, it's a long time, but we'll keep trying."[11]

References

- ↑ https://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/programs/585833

- ↑ "Finger of suspicion"

- ↑ "The sister and husband of a flight attendant who..."

- ↑ "Lockerbie handlers say no intruders in loading bay"

- ↑ "Mystery of extra Pan Am 103 crew member remains"

- ↑ "Report of the Fatal Accident Inquiry relating to the Lockerbie Air Disaster"

- ↑ "Legacy of Lockerbie: part 2 – The empty auditorium"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Heathrow alert was ignored"

- ↑ "Date set for Lockerbie appeal"

- ↑ "Abdelbaset Al-Megrahi: Lockerbie bomber's appeal date set"

- ↑ "Relative's doubts over Lockerbie case"