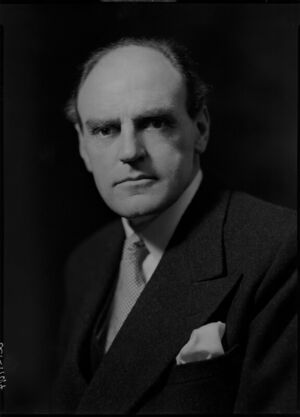

John Reith

| |

| Born | John Charles Walsham Reith 20 July 1889 Stonehaven, Kincardineshire, Scotland |

| Died | 20 July 1889 (Age 0) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Alma mater | • The Glasgow Academy • Gresham’s School |

| Religion | Presbyterianism |

| Founder of | BBC |

First Director-General of the British Broadcasting Corporation

| |

John Charles Walsham Reith, 1st Baron Reith was a Scottish broadcasting executive who established the tradition of public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom. In 1922, he was employed by the BBC (British Broadcasting Company Ltd.) as its general manager; in 1923 he became its managing director and in 1927 he was employed as the Director-General of the British Broadcasting Corporation created under a royal charter. His concept of broadcasting as a way of educating the masses marked for a long time the BBC and similar organisations around the world.[1]

Contents

Early Life

John Reith was born in Stonehaven, Kincardineshire. He is the youngest of seven children of the Reverend George Reith, a member of the Presbyterian Church.

BBC Director-General

After answering an advertisement, he was operational director of the BBC, when it was born on November 14, 1922 as a consortium of radio companies. In 1927, when it took on its current name, he was promoted to general manager.

The general strike

In 1926, Reith came into conflict with the government during the 1926 United Kingdom general strike. The BBC bulletins reported, without comment, all sides in the dispute, including the Trades Union Congress's and of union leaders. Reith attempted to arrange a broadcast by the opposition Labour Party but it was vetoed by the government, and he had to refuse a request to allow a representative Labour or Trade Union leader to put the case for the miners and other workers.

Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin made a national broadcast about the strike from Reith's house and coached by Reith. When Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, asked to make a broadcast in reply, Reith supported the request. However, Baldwin was "quite against MacDonald broadcasting" and Reith unhappily refused the request.[2] MacDonald complained that the BBC was "biased" and was "misleading the public" while other Labour Party figures were just as critical. Philip Snowden, the former Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, was one of those who wrote to the Radio Times to complain.

Reith's reply also appeared in the Radio Times, admitting the BBC had not had complete liberty to do as it wanted. He recognised that at a time of emergency the government was never going to give the company complete independence, and he appealed to Snowden to understand the constraints he had been under.

The Labour leadership was not the only high-profile body denied a chance to comment on the strike. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, wanted to broadcast a "peace appeal" drawn up by church leaders which called for an immediate end to the strike, renewal of government subsidies to the coal industry and no cuts in miners' wages.

Davidson telephoned Reith about his idea on 7 May, saying he had spoken to the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, who had said he would not stop the broadcast, but would prefer it not to happen. Reith later wrote: "A nice position for me to be in between Premier and Primate, bound mightily to vex one or other."[3]

Reith asked for the government view and was advised not to allow the broadcast because, it was suspected, that would give the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, an excuse to commandeer the BBC. Churchill had already lobbied Baldwin to that effect. Reith contacted the Archbishop to turn him down and explain that he feared if the talk went ahead, the government might take the company over.

Although Churchill wanted to commandeer the BBC to use it "to the best possible advantage", Reith wrote that Baldwin's government wanted to be able to say "that they did not commandeer [the BBC], but they know that they can trust us not to be really impartial".[2]

Reith admitted to his staff that he regretted the lack of TUC and Labour voices on the airwaves. Many commentators[Who?] have seen Reith's stance during that period as pivotal in establishing the state broadcaster's enduring reputation for impartiality.

Reid came in conflict with Winston Churchill again in December 1929, when the former Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer offered the BBC director-general money in exchange for time speaking on the air, and the latter replying that "the American system which gives access to broadcasting against payment is disrespectful of any consideration of content or equity".

Attitude to fascism

In 1975, excerpts from Reith's diary were published which showed he had, during the 1930s, harboured pro-fascist views.On 9 March 1933, he wrote: "I am pretty certain ... that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again. They are being ruthless and most determined." After the July 1934 Night of the Long Knives, in which the Nazis ruthlessly exterminated their internal dissidents, Reith wrote: "I really admire the way Hitler has cleaned up what looked like an incipient revolt. I really admire the drastic actions taken, which were obviously badly needed." After Czechoslovakia was invaded by the Nazis in 1939 he wrote: "Hitler continues his magnificent efficiency.[4] [5]

Reith also expressed admiration for Benito Mussolini.[6] Reith's daughter, Marista Leishman, wrote that in the 1930s her father did everything possible to keep Winston Churchill and other anti-appeasement Conservatives off the airwaves.

Departure

By 1938, Reith had become discontented with his role as Director-General, asserting in his autobiography that the organisational structure of the BBC, which he had created, had left him with insufficient work to do. He was invited by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to become chairman of Imperial Airways, the country's most important airline and one which had fallen into public disfavour because of its inefficiency. Some commentators[7] have suggested a conspiracy amongst the Board of Governors to remove Reith, but that has never been proved, and there is no record of such a thing in Reith's own memoir[8].

Later career

In 1940, Reith was appointed Minister of Information in Chamberlain's government. So as to perform his full duties, he became a member of parliament (MP) for Southampton. When Chamberlain fell, Churchill became Prime Minister and moved Reith to the Ministry of Transport. Reith was subsequently moved to become First Commissioner of Works which he held for the next two years, through two restructurings of the job, and was also transferred to the House of Lords by being created Baron Reith.

During that period, the city centres of Coventry, Plymouth and Portsmouth were destroyed by German bombing. Reith urged the local authorities to begin planning postwar reconstruction. He was dismissed from his government post at a very difficult time for Churchill in 1942, following the loss of Singapore. Pressured by Tory backbenchers who wanted a Conservative in the Information role, Reith was replaced by Duff Cooper.

In 1946, he was appointed chairman of the Commonwealth Telecommunications Board, a post he held until 1950. He was then appointed chairman of the Colonial Development Corporation which he held until 1959. In 1948, he was also appointed the chairman of the National Film Finance Corporation, an office he held until 1951.

Related Quotation

| Page | Quote | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBC | “The BBC began in 1922, just before the corporate press began in America. Its founder was Lord John Reith, who believed that impartiality and objectivity were the essence of professionalism. In the same year the British establishment was under siege. The unions had called a general strike and the Tories were terrified that a revolution was on the way. The new BBC came to their rescue. In high secrecy, Lord Reith wrote anti-union speeches for the Tory Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and broadcast them to the nation, while refusing to allow the labor leaders to put their side until the strike was over. So, a pattern was set. Impartiality was a principle certainly: a principle to be suspended whenever the establishment was under threat. And that principle has been upheld ever since.” | John Pilger | 16 June 2007 |

Related Document

| Title | Type | Publication date | Author(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document:BBC's biased and inaccurate reporting of anti-semitism allegations towards Jeremy Corbyn | Letter | 7 August 2018 | Pamela Blakelock | "We regret that the BBC has failed to comply with its own codes with regard to impartiality and accuracy. Given the gravity of allegations of anti-semitism, the role performed by the BBC is all the more critical if it is to live up to Reithian principles of informing the public." |

References

- ↑ Lord Reith – Creator of British broadcasting and first BBC Director-General". The Times. 17 June 1971. p. 17.

- ↑ Jump up to: a b https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/aug/18/-sp-bbc-report-facts-impartial

- ↑ McIntyre, I. (1993), The Expense of Glory: Life of John Reith, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-215963-0 page 143

- ↑ Paulu, Burton (1981), Television and Radio in the United Kingdom, Palgrave Macmillan page 135

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=G5H7x-OnqpEC&pg=PA17

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20140219060057/http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/in-the-media/churchill-in-the-news/692--reith-of-the-bbc

- ↑ Boyle, Andrew (1972) Only the Wind will Listen, Hutchinson

- ↑ McIntyre, I. (1993), The Expense of Glory: Life of John Reith, HarperCollins page 238

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here