Hydra

(animal, nanotechnology?) | |

|---|---|

| |

| A microscope analysis of some Covid-19 vaccines done by Dr. Carrie Madej observed 'creatures' similar to the hydra, leading to speculation that a mini/nano version could have been made to survive in the human body. |

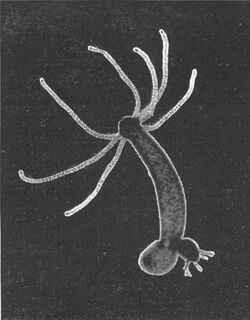

Hydra is a genus of small, fresh-water organisms. Biologists are especially interested in Hydra because of its remarkable properties of regeneration and renewal and seeming immortality. Hydra Vulgaris is one of the 6 “model organisms” by the Human Genome Project and its neural networks ('brain') has been completely mapped.

A microscope analysis of some Moderna and Johnson and Johnson Covid-19 vaccines samples, done by Dr. Carrie Madej observed 'creatures' similar to the hydra, leading to speculation that a programmable mini/nano version could have been made to survive in the human body.[1]

Overview

| In 2017, Harvard scientists announced they had mapped every neuron in Hydras, opening up for "reading and writing neural code". A 2020 video from The Economist mentions hydras in the context of mind control, as part of the 6bn Brain Initiative. |

Hydra has a tubular, radially symmetric body up to 10 mm (0.39 in) long when extended, secured by a simple adhesive foot known as the basal disc. Gland cells in the basal disc secrete a sticky fluid that accounts for its adhesive properties.[2]

At the free end of the body is a mouth opening surrounded by one to twelve thin, mobile tentacles. Each tentacle, or cnida (plural: cnidae), is clothed with highly specialised stinging cells called cnidocytes. Cnidocytes contain specialized structures called nematocysts, which look like miniature light bulbs with a coiled thread inside. At the narrow outer edge of the cnidocyte is a short trigger hair called a cnidocil. Upon contact with prey, the contents of the nematocyst are explosively discharged, firing a dart-like thread containing neurotoxins into whatever triggered the release. This can paralyze the prey, especially if many hundreds of nematocysts are fired.

Hydra has two main body layers, which makes it "diploblastic". The layers are separated by mesoglea, a gel-like substance. The outer layer is the epidermis, and the inner layer is called the gastrodermis, because it lines the stomach. The cells making up these two body layers are relatively simple. A single Hydra is composed of 50,000 to 100,000 cells which consist of three specific stem cell populations that will create many different cell types. These stem cells will continually renew themselves in the body column.[3] Hydras have two significant structures on their body: the "head" and the "foot". When a Hydra is cut in half, each half will regenerate and form into a small Hydra; the "head" will regenerate a "foot" and the "foot" will regenerate a "head". If the Hydra is sliced into many segments then the middle slices will form both a "head" and a "foot".[4]

Nervous system

| The Undying Hydra: A Freshwater Mini-Monster That Defies Aging |

The nervous system of Hydra is a nerve net, which is structurally simple compared to more derived animal nervous systems. Hydra does not have a recognizable brain or true muscles. Nerve nets connect sensory photoreceptors and touch-sensitive nerve cells located in the body wall and tentacles.

The structure of the nerve net has two levels:

- level 1 – sensory cells or internal cells; and,

- level 2 – interconnected ganglion cells synapsed to epithelial or motor cells.

Some have only two sheets of neurons.[5]

The University of California at Davis received a 1.5 million dollar grant in 2018 from the National Science Foundation’s EDGE (Enabling Discovery Through Genomic Tools) program to further study the Hydra Vulgaris and probe its gene sequences and neural networks while studying its unique regeneration of neurons.[6]

Motion and locomotion

If Hydra are alarmed or attacked, the tentacles can be retracted to small buds, and the body column itself can be retracted to a small gelatinous sphere. Hydra generally react in the same way regardless of the direction of the stimulus, and this may be due to the simplicity of the nerve nets.

Hydra are generally sedentary or sessile, but do occasionally move quite readily, especially when hunting. They have two distinct methods for moving – 'looping' and 'somersaulting'. They do this by bending over and attaching themselves to the substrate with the mouth and tentacles and then relocate the foot, which provides the usual attachment, this process is called looping. In somersaulting, the body then bends over and makes a new place of attachment with the foot. By this process of "looping" or "somersaulting", a Hydra can move several inches (c. 100 mm) in a day. Hydra may also move by amoeboid motion of their bases or by detaching from the substrate and floating away in the current. Reproduction and Life Expectancy

In contrast to most other cnidarians, freshwater polyps lack the medusa generation, they only occur in the form of polyps and do not show a generation change (metagenesis). Hydra can reproduce asexually, in the form of sprouting new polyps on the stalk of the parent polyp, through longitudinal and transverse division, and under certain circumstances sexually. These circumstances have not yet been fully clarified, but lack of food plays a major role. The animals can be male, female or also hermaphrodite. Sexual reproduction is initiated by the formation of sex cells in the animal's wall. Characteristic sperm-filled protrusions ("testicles") form in the upper third of the animal and an ovary with a large egg cell in the lower third of a hermaphrodite animal. The eggs are still fertilized in the epidermal wall. The fertilized egg is either actively attached to the ground by the animal or passively sinks to the ground. However, it can also be surrounded by a periderm cover and last for months in this form. In this form, it survives drying out and freezing through. Then a small polyp slips out of the peridermal cover.

With polyps, the risk of death does not increase with age. Under ideal conditions, it has a life expectancy of several centuries. [2] regeneration

The freshwater polyps have a remarkable ability to regenerate. Instead of repairing damaged cells, they are constantly being replaced as stem cells divide and sometimes differentiate. A freshwater polyp renews itself practically completely within five days. The ability to even replace nerve cells has so far been considered unique in the animal kingdom. It should be noted, however, that the nerve cells of freshwater polyps are very primitive types of neurons. Some populations that have been observed for long periods of time have shown no signs of aging. Under constant optimal environmental conditions, the age of a freshwater polyp may not be limited. [3] In 2012, researchers at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (CAU) described the transcription factor FOXO3, discovered in Hydra in 2010, as a critical factor in the regulation of stem cell proliferation. A gene product that is also found in vertebrates and humans. This suggests that mechanisms that control longevity are evolutionarily conserved. [4]

Another special property of freshwater polyps is that if their cells are separated from one another, they find each other again or new polyps grow out of them. A new individual can grow from single pieces of 1/200 the mass of an adult polyp. For example, a freshwater polyp that has been pushed through a net can reassemble itself. This property is of great interest for biotechnology.

COVID vaccines

September 30, 2021, Dr. Carrie Madej stated that she had found what she believes is the hydra vulgaris, "a seemingly self-conscious spidery-looking organism coming to the edge of the plate and seemingly rising up to look at the eyepiece of the microscope."[7]

- ↑ https://rumble.com/vn7gur-critically-thinking-with-dr.-t-and-dr.-p-episode-64-spec-guests-dr.-m-and-d.html

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_model_organisms

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4463768

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9971/

- ↑ https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cub.2017.03.040

- ↑ https://biology.ucdavis.edu/news/15-million-nsf-grant-help-make-hydra-better-model-studying-regeneration

- ↑ https://rumble.com/vn7gur-critically-thinking-with-dr.-t-and-dr.-p-episode-64-spec-guests-dr.-m-and-d.html