Document:Theresa May's Misconduct In Public Office

| Theresa May's Misconduct in Public Office offence arises from what is alleged to have been her wrongful activation on 29 March 2017 of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union |

Subjects: EU Referendum, Brexit, Lisbon Treaty, Article 50, Theresa May, Misconduct in Public Office

Source: StopBrexitMisconduct (Link)

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Theresa May's Misconduct In Public Office

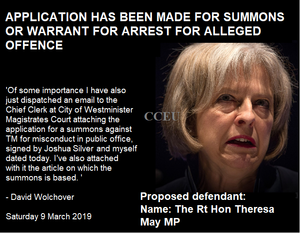

On Saturday, 9 March 2019, the barrister David Wolchover and Professor Joshua Silver, Oxford University Professor of Physics, laid a joint information by way of an application to the City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court for the issuing of a summons against the Prime Minister, Mrs Theresa May, alleging the Common law offence of Misconduct in Public Office.[1] The offence arises from what is alleged to have been her wrongful activation on 29 March 2017 of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union.[2]

The particulars of the allegation as set out in the terms of the application are that when on 29 March 2017 Mrs May activated Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union in pursuance of the authority given to her by Parliament she exclusively applied the outcome of the European Referendum of 23 June 2016, knowing that the referendum as constituted by the European Union Referendum Act 2015 was merely advisory and therefore that general principles of rationality, good governance and constitutional convention on the formation of policy required her as a matter of constitutional imperative to consider all relevant factors, principally diverse impact assessments on the consequences of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union. The dire consequences of her failure to have regard to those factors and to have applied them in making her decision to activate Article 50 have now become manifest in the turmoil and panic surrounding the run-up to “exit day” this coming March 29.

The summary of the circumstances as set out in the application are as follows:

In pursuance of the European Union Referendum Act 2015 (EURA) the EU Referendum was held on 23 June 2016. Of those who participated in the ballot 51.89 per cent voted in favour of the United Kingdom withdrawing from the Union as against 48.11 per cent voted to Remain. Those voting to Leave represented no more than 37 per cent of the registered electorate.

Constitutionally, the Referendum was merely advisory (and not binding). As such it could only be influential in guiding the formation of government policy on the question of whether the UK ought to Remain in or Leave the European Union. Nonetheless Government ministers have consistently sought to treat the outcome as decisive rather than influential, pledging themselves to honour “or respect” – that is to say, to implement – the majority opinion of those who cast their votes in the ballot.

Those statements enjoyed no more than political force, as the Supreme Court confirmed in the case of "Gina Miller v The Secretary of State for Departing from the European Union" (hereafter Miller). However, they did not exempt the government from the fundamental and conventional duty required in all reasonable and proper policy-formation and decision making, of considering all relevant factors.

As the Administrative Court held in the case of Webster v The Secretary of State for Departing from the European Union, section 1(1) of the European Union (Notice of Withdrawal) Act authorised (but did not command) the defendant, in her capacity of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to make the withdrawal decision on behalf of the United Kingdom in accordance with Article 50(1) of the Treaty on European Union. In pursuance of that delegated power, the defendant, on 29 March 2017, wrote to Donald Tusk, President of the Council of Europe, notifying him under Article 50(2), TEU, of the United Kingdom’s intention to withdraw from the European Union.

In making the withdrawal decision in pursuance of her delegated power the defendant failed to pay any significant or systematic regard to any factors relevant to the decision, notably a range of political, economic, social, strategic and security impact assessments likely to follow withdrawal. This was in spite of the fact that she was obligated to do so

- (a) by the statutory non-binding nature of the referendum; and,

- (b) by the inherent obligation of good and effective governance requiring an informed and comprehensive review of relevant and reasonably tangible predictions.

The evidence of such failure emerges

- (a) from the many equivocations and inconsistent statements uttered by ministers on the floor of the House of Commons (described in the annexed article); and,

- (b) from a Freedom of Information disclosure by the Cabinet Office on 23 January 2019 revealing that no impact assessments of the kind comprehensively detailed in the FOI request are held on file in the Cabinet Office, which they would assuredly have been had the Prime Minister perused any such assessments.

The consequences of the defendant’s failure to consider the impact of activating Article 50 are now being demonstrated graphically by the turmoil and negative predictions being reported on a daily basis.

The defendant’s failure was so serious and so knowing and deliberate as to amount to the offence of Misconduct in Public Office.

The detailed argument is set out in David Wolchover’s short treatise “Did activating Article 50 constitute an indictable offence?” in Criminal Law and Justice Scrutineer, accessible at www.DavidWolchover.co.uk.[3]