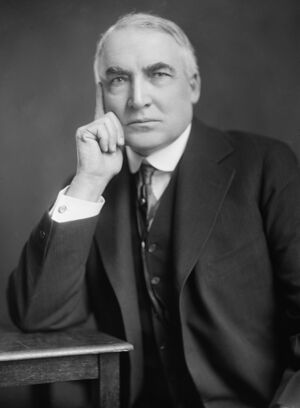

Warren Harding

(Editor, politician) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Warren Gamaliel Harding November 2, 1865 Blooming Grove, Ohio, U.S. | |||||||||||||||

| Died | August 2, 1923 (Age 57) San Francisco, California, U.S. | |||||||||||||||

Cause of death | "heart problem" | |||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Ohio Central College | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Baptist | |||||||||||||||

| Children | Elizabeth Ann Blaesing | |||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Florence Kling | |||||||||||||||

| Victim of | premature death | |||||||||||||||

| Party | Republican | |||||||||||||||

Died under suspicious circumstances, as did a number of people around him.

| ||||||||||||||||

Warren Gamaliel Harding was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular U.S. presidents to that point. Although suffering from heart problems, his death happened under suspicious circumstances. The geopolitical intrigues surrounding the Teapot Dome corruption scandal are still not cleared up.

Early career

Harding lived in rural Ohio all his life, except when political service took him elsewhere. As a young man, he bought The Marion Star and built it into a successful newspaper. After serving in the Ohio State Senate from 1900 to 1904, Harding was lieutenant governor for two years. He was defeated for governor in 1910, but was elected to the United States Senate in 1914, the state's first direct election for that office. Harding ran for the Republican nomination for president in 1920, and was considered a long shot until after the convention began. The leading candidates could not gain the needed majority, and the convention deadlocked. His support gradually grew until he was nominated on the tenth ballot. Harding conducted a front porch campaign, remaining for the most part in Marion and allowing the people to come to him, and running on a theme of a return to normalcy of the pre-World War period. He won in a landslide over Democrat James M. Cox and Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs, to become the first sitting senator elected president.

President

Harding appointed a number of well-regarded figures to his cabinet, including Andrew Mellon at Treasury, Herbert Hoover at Commerce, and Charles Evans Hughes at the State Department. A major foreign policy achievement came with the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922, in which the world's major naval powers agreed on a naval limitations program that lasted a decade. Harding released political prisoners who had been arrested for their opposition to the World War. His cabinet members Albert B. Fall (Interior Secretary) and Harry Daugherty (Attorney General) were each later tried for corruption in office; Fall was convicted though Daugherty was not. These and other scandals greatly damaged Harding's posthumous reputation; he is generally regarded as one of the worst presidents in U.S. history. Harding died of a heart attack in San Francisco while on a western tour, and was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge.

Teapot Dome

- Full article: Teapot Dome

- Full article: Teapot Dome

There administration is surrounded with allegations of corruption. There are irregularities in the distribution of seized enemy assets. Convicted mafia bosses are allowed to travel freely around the world thanks to the protection of Justice Minister Harry Daugherty. A lively trade with special permits for alcohol production and storage is developed during the beginning of the Prohibition.

The Teapot Dome scandal was the biggest bribery scandal involving the Harding administration. It centered around an oil reserve in Wyoming which was one of three set aside for the use of the Navy in a national emergency. In March 1921 Harding appointed Albert Fall as Secretary of the Interior. Soon afterwards he persuaded Edwin Denby, the Secretary of the Navy, that he should take over responsibility for the Naval Reserves at Elk Hills and Teapot Dome. Later that year Fall decided that two of his friends, Harry F. Sinclair (Mammoth Oil Corporation) and Edward L. Doheny (Pan-American Petroleum and Transport Company), should be allowed to lease part of these Naval Reserves.

However, what came out in the public covered a power struggle in the oil industry, in a campaign arranged by the Standard Oil subsidiary Vacuum Oil against Sinclair. The struggle is about the vast Russian oil reserves. The huge oil reserves around Baku had been developed by Rothschild, the Nobel brothers and Royal Dutch/Shell. The cooperation with the Tsarist security service Okrana had worked well for the oil companies, so the oil companies supported the Whites against the Red Army in the Russian civil war. Harry Sinclair contributed an 8,000-strong private army to the counter-revolution in 1919. However, the Bolsheviks asserted themselves as a the ruling power in the region.

Sinclair made amends, and boasted of his friendship with Lenin and meets with the Soviet ambassador Leonid Krassin in London in 1923. Krassin previously worked as an oil engineer in Baku. Shortly afterwards, Sinclair traveled to Moscow with a large entourage. A contract is signed there, commissioning Sinclair to equip the oil fields in Baku and oil wells in North Sakhalin with the latest drilling technology. He pledges to invest at least $ 115 million in this upgrade. Sinclair guarantees the Soviet government for a gigantic loan package for the Bolsheviks in the USA.

Just by chance, at this crucial moment in the USA, a press campaign was sparked which, as a "Teapot Dome Scandal", ignores Doheny's share of guilt and inseparably welds the name Sinclair together with the biggest corruption affair in the USA. After this, it is unthinkable that anyone in the East Coast financial establishment could join a loan consortium led by Harry Sinclair. Sinclair cannot fulfill his contractual terms and the Soviet government terminates the contract.[1]

In 1925 a very fruitful cooperation began between the Standard Oil subsidiary Vacuum Oil and the Soviet oil distributor Azneft. 800,000 tons of crude oil are shipped from the USSR to Egypt in order to create trouble for Shell by dumping goods. Standard Oil of New Jersey propagandist Ivy Lee generates positive reports about the USSR in the US newspapers. Esso then starts modernizing the Soviet oil infrastructure on a large scale. Standard Oil of New Jersey's main bank Chase finances a a modern train line from Grozny to the border of the Soviet Union.[1]

Death

In 1998, previously unpublished documents by Harding's doctor, Joel T. Boone, show that his patient suffered from high blood pressure and cardiac problems many years before he died. In addition, at the age of 24, Harding completed a stay in a sanatorium for several months after a nervous breakdown.[2]

The presidential couple stopped in Vancouver on the way back from a summer vacation in Alaska. At lunch the president suddenly felt very nauseous. Harding went to bed early on the evening of July 27, 1923, a few hours after giving a speech at the University of Washington. Later that night, he called for his physician Charles E. Sawyer, complaining of pain in the upper abdomen. The summer visitors still traveled to San Francisco, where Harding died on August 2, 1923 at the age of 57. Florence Harding did not consent to have the president autopsied,[3] and had his body embalmed one hour after his death.

The New York Times attributed the Harding's sudden death to a “stroke of apoplexy.”[4]

Dr. Ray Lyman Wilbur, who was also the president of Stanford University, was at the hotel when Harding arrived for treatment, and he recalled the events that followed in his memoirs. “We shall never know exactly the immediate cause of President Harding's death since every effort that was made to secure an autopsy met with complete and final refusal.” [5]

One theory is that Harding’s preferred doctor, Charles Sawyer, gave the president “purgatives” to hasten his recovery. The remedies issued by Sawyer, who wasn’t a trained physician, may have aggravated Harding’s heart condition.[6]

Other deaths

Florence Harding died in 1924. Dr. Sawyer died a few months after his prominent patient. Also shortly after Harding, his personal advisor, Colonel Felder, died; so did John King, the partner of Harding's patron Harry M. Daugherty, and Daugherty's associate Hateley.

References

- ↑ a b https://apolut.net/history-der-raetselhafte-tod-des-praesidenten-harding

- ↑ https://doctorzebra.com/prez/g29.htm

- ↑ Murray, Robert K. (1969). The Harding Era 1921–1923: Warren G. Harding and his Administration. University of Minnesota Press. page 449-50

- ↑ https://www.zerohedge.com/political/strange-death-warren-g-harding

- ↑ https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/blog/after-90-years-president-warren-hardings-death-still-unsettled

- ↑ https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/09/04/bay-area-history-on-95th-anniversary-of-president-warren-g-hardings-death-san-francisco-man-renews-story-of-poisoning/