Document:Midnight in the Congo

| A probing analysis of evidence that both Patrice Lumumba and Dag Hammarskjold were assassinated by agents of the UK and US intelligence services |

Source: Unknown

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Contents

The Assassination of Lumumba and the Mysterious Death of Dag Hammarskjold

"In Elizabethville, I do not think there was anyone there who believed that his death was as accident." — U.N. Representative Conor Cruise O’Brien on the death of U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold

"A lot has not been told." — Unnamed U.N. official, commenting on same

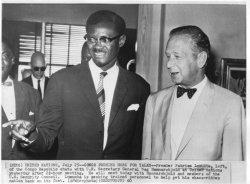

The CIA has long since acknowledged responsibility for plotting the murder of Patrice Lumumba, the popular and charismatic leader of the Congo. But documents have recently surfaced that indicate the CIA may well have been involved in the death of another leader as well, U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold. Hammarskjold died in a plane crash enroute to meet Moise Tshombe, leader of the breakaway (and mineral-rich) province of Katanga. At the time of his death, there was a great deal of speculation that Hammarskjold had been assassinated to prevent the U.N. from bringing Katanga back under the rule of the central government in the Congo. Fingers were pointed at Tshombe’s mercenaries, the Belgians, and even the British. Hardly anyone at the time considered an American hand in those events. However, two completely different sets of documents point the finger of culpability at the CIA. The CIA has denied having anything to do with the murder of Hammarskjold. But we all know what the CIA’s word is worth in such matters.

In the previous issue of Probe, Jim DiEugenio explored the history of the Congo at this point in time, and the difference between Kennedy’s and Eisenhower’s policies toward it. In the summer of 1960, the Congo was granted independence from Belgium. The Belgians had not prepared the Congo to be self-sufficient, and the country quickly degenerated into chaos, providing a motive for the Belgians to leave their troops there to maintain order. While the Belgians favored Joseph Kasavubu to lead the newly independent nation, the Congolese chose instead Patrice Lumumba as their Premier. Lumumba asked the United Nations, headed then by Dag Hammarskjold, to order the Belgians to withdraw from the Congo. The U.N. so ordered, and voted to send a peacekeeping mission to the Congo. Impatient and untrusting of the U.N., Lumumba threatened to ask the Soviets for help expelling the Belgian forces. Like so many nationalist leaders of the time, Lumumba was not interested in Communism. He was, however, interested in getting aid from wherever he could, including the Soviets. He had also sought and, for a time, obtained American financial aid.

Hatching an Assassination

In 1959, Lumumba had visited businessmen in New York, where he stated unequivocally, "The exploitation of the mineral riches of the Congo should be primarily for the profit of our own people and other Africans." Affected minerals included copper, gold, diamonds, and uranium. Asked whether the Americans would still have access to uranium, as they had when the Belgians ran the country, Lumumba responded, "Belgium doesn’t produce any uranium; it would be to the advantage of both our countries if the Congo and the U.S. worked out their own agreements in the future." [2] Investors in copper and uranium in the Congo at that time included the Rockefellers, the Guggenheims and C. Douglas Dillon. Dillon participated in the NSC meeting where the removal of Lumumba was discussed. According to NSC minutes from the July 21, 1960 meeting, Allen Dulles, head of the CIA and former lawyer to the Rockefellers, sounded the alarm regarding Lumumba:

Mr. Dulles said that in Lumumba we were faced with a person who was Castro or worse ... Mr. Dulles went on to describe Mr. Lumumba’s background which he described as "harrowing" ... It is safe to go on the assumption that Lumumba has been bought by the Communists; this also, however, fits with his own orientation. [3]

Lawrence Devlin, referenced in the Church Committee report under the pseudonym "Victor Hedgman", was the CIA Station Chief in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). On August 18th, Devlin cabled Dulles at CIA headquarters the following message:

EMBASSY AND STATION BELIEVE CONGO EXPERIENCING CLASSIC COMMUNIST EFFORT TAKEOVER GOVERNMENT.... WHETHER OR NOT LUMUMBA ACTUALLY COMMIE OR JUST PLAYING COMMIE GAME TO ASSIST HIS SOLIDIFYING POWER, ANTI-WEST FORCES RAPIDLY INCREASING POWER CONGO AND THERE MAY BE LITTLE TIME LEFT IN WHICH TAKE ACTION TO AVOID ANOTHER CUBA. [4]

The day this cable was sent, the NSC held another meeting at which Lumumba was discussed. Robert Johnson, a member of the NSC staff, testified to the Church Committee that sometime during the summer of 1960, at an NSC meeting, he heard President Eisenhower make a comment that sounded to him like a direct order to assassinate Lumumba:

At some time during that discussion, President Eisenhower said something—I can no longer remember his words—that came across to me as an order for the assassination of Lumumba.... I remember my sense of that moment quite clearly because the President’s statement came as a great shock to me. [5]

The Church Committee report on the Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders recorded that Johnson "presumed" Eisenhower made the statement while "looking toward the Director of Central Intelligence." [6] With or without direct authorization, on August 26, 1960, Allen Dulles took the bull by the horns. He cabled Devlin in the Congo station the following message:

IN HIGH QUARTERS HERE IT IS THE CLEAR-CUT CONCLUSION THAT IF [LUMUMBA] CONTINUES TO HOLD HIGH OFFICE, THE INEVITABLE RESULT WILL AT BEST BE CHAOS AND AT WORST PAVE THE WAY TO COMMUNIST TAKEOVER OF THE CONGO WITH DISASTROUS CONSEQUENCES FOR THE PRESTIGE OF THE U.N. AND FOR THE INTERESTS OF THE FREE WORLD GENERALLY. CONSEQUENTLY WE CONCLUDE THAT HIS REMOVAL MUST BE AN URGENT AND PRIME OBJECTIVE AND THAT UNDER EXISTING CONDITIONS THIS SHOULD BE A HIGH PRIORITY OF OUR COVERT ACTION. [7]

Assassination requests would normally have gone to Richard Bissell. Because Bissell was away on vacation, Dulles told Eisenhower he would take care of Lumumba. According to Dulles family biographer Leonard Mosley, Dulles put Richard Helms in charge of preparing the assassination plot. A few days later, Helms produced a "blueprint" for the "elimination" of Lumumba. [8] Although the Church Committee report includes no references to Helms’ involvement, this is certainly plausible. One of the first people involved in the plot to kill Lumumba was Dr. Sidney Gottlieb, who enjoyed Richard Helms’ patronage within the agency. As Helms moved up in the Agency, so too did Gottlieb. [9] Gottlieb is identified as "Joseph Scheider" in the Church Committee report. Gottlieb was the grandfather of the CIA’s mind control programs, as well as the producer of exotic and deadly biotoxins for the CIA’s "Executive Action" programs.

After returning from vacation, Bissell approached Bronson Tweedy, head of the CIA’s Africa Division, about exploring the feasibility of assassinating Lumumba. Gottlieb also conversed with Bissell, and claimed Bissell had indicated they had approval from "the highest authority" to proceed with assassinating Lumumba.

By September 5, the situation in the Congo had deteriorated badly. Kasavubu made a radio address to the nation in which he dismissed Lumumba and six Ministers. Thirty minutes later, Lumumba gave a radio address in which he announced that Kasavubu was no longer the Chief of State. Lumumba called upon the people to rise up against the army. Just over a week later, Joseph Mobutu claimed he was going to neutralize all parties vying for control and would bring in "technicians" to run the country. [10] According to Andrew Tully, Mobutu was "discovered" by the CIA, and was used by CIA to take charge of the country when the favored Kasavubu lost authority. The CIA’s relationship with Mobutu is pertinent to the ultimate question of the CIA’s final culpability in the assassination of Lumumba. Tully refers to Mobutu as "the CIA’s man" in the Congo. [11] When Mobutu claimed power, he called on the Soviet-bloc embassies to vacate the country within 48 hours. [12] John Prados wrote that Mobutu was "cultivated for weeks by American diplomats and CIA officers, including Station Chief Devlin." [13]

Gottlieb was sent to the Congo to meet Devlin. The CIA cabled Devlin that Gottlieb, under the alias of "Joseph Braun", would arrive on approximately September 27. Gottlieb was to announce himself as "Joe from Paris". The cable bore a special designation of PROP. Tweedy told the Church Committee that the PROP designator was established specifically to refer to the assassination operation. According to Tweedy, its presence restricted circulation to Dulles, Bissell, Tweedy, Tweedy’s deputy, and Devlin. Tweedy sent a cable through the PROP channel saying that if plans to assassinate Lumumba were given a green light, the CIA should employ a third country national to conceal the American role. [14] Clearly, from the start, deniability was the highest concern in the assassination plotting.

The toxin was supposed to be administered to Lumumba orally through food or toothpaste. This effort was clearly unsuccessful, if it had ever been fully attempted. Gottlieb’s and Devlin’s testimony conflicted regarding the disposal of the toxins. Both said they disposed of all the toxins in the Congo River. But if one of them did this, the other is lying, and both could be lying to protect the continued presence of toxic substances, as indicated by a cable from Leopoldville to Tweedy, dated 10/7/60:

[GOTTLIEB] LEFT CERTAIN ITEMS OF CONTINUING USEFULNESS. [DEVLIN] PLANS CONTINUE TRY IMPLEMENT OP. [15]

In October 1960, Devlin cabled Tweedy a cryptic request for him to send a rifle with a silencer via diplomatic pouch, a violation of international law:

IF CASE OFFICER SENT, RECOMMEND HQS POUCH SOONEST HIGH POWERED FOREIGN MAKE RIFLE WITH TELESCOPIC SCOPE AND SILENCER. HUNTING GOOD HERE WHEN LIGHTS RIGHT. HOWEVER AS HUNTING RIFLES NOW FORBIDDEN, WOULD KEEP RIFLE IN OFFICE PENDING OPENING OF HUNTING SEASON. [16]

There is no evidence to suggest a silenced rifle was or was not pouched at this point. The CIA did, however, send rifles to be used to assassinate Rafael Trujillo by diplomatic pouch to the Dominican Republic.

A senior CIA officer from the Directorate of Plans was dispatched to the Congo to aid in the assassination attempt. Justin O’Donnell, referred to in the Church Committee records as "Father Michael Mulroney", refused to be involved directly in a murder attempt against Lumumba, saying succinctly, "murder corrupts". [17] But he was not opposed to aiding others in the removal of Lumumba. He told the Church Committee:

I said I would go down and I would have no compunction about operating to draw Lumumba out [of U.N. custody], to run an operation to neutralize his operations.... [18]

O’Donnell planned to lure Lumumba away from UN protection and then turn Lumumba over to his enemies, who would surely kill him. "I am not opposed to capital punishment", O’Donnell explained to the Church Committee. He just wasn’t going to pull the trigger himself.

O’Donnell requested that CIA asset QJ/WIN be sent to the Congo for his use. O’Donnell claimed he wanted QJ/WIN to participate in counterespionage. (The CIA’s IG report, however, indicated that QJ/WIN had been recruited to assassinate Lumumba. [19]) O’Donnell’s plan, which appears to have been successful, was for QJ/WIN to penetrate the defenses around Lumumba and encourage Lumumba to "escape" his UN guard. Once in the open, Mobutu’s forces could then arrest Lumumba and kill him. In the end, this is exactly what appears to have happened. Although O’Donnell denied that QJ/WIN had anything to do with Lumumba’s escape, arrest and murder, a cable to CIA’s finance division from William Harvey implies otherwise:

QJ/WIN was sent on this trip for a specific, highly sensitive operational purpose which has been completed. [20]

Another CIA operative, code-named WI/ROGUE, was dispatched to aid in the Congo operation. The CIA provided WI/ROGUE plastic surgery and a toupee "so that Europeans traveling in the Congo would not recognize him." WI/ROGUE was described as a man who would "dutifully undertake appropriate action for its execution without pangs of conscience. In a word, he can rationalize all actions." [21]

WI/ROGUE was apparently assigned to Devlin. a report prepared for the CIA’s Inspector General described the preparation to be undertaken for his use:

In connection with this assignment, WI/ROGUE was to be trained in demolitions, small arms, and medical immunization. [22]

While in the Congo, WI/ROGUE undertook to organize an "Execution Squad." One of the people he attempted to recruit was QJ/WIN. QJ/WIN did not know whether WI/ROGUE was CIA or not, and refused to join him. Both O’Donnell and Devlin claimed WI/ROGUE had no authority to convene an assassination team. But that assertion seems hard to believe, given that a capable assassin was assigned to a group plotting the permanent removal of Lumumba. And given that WI/ROGUE was to be trained in "medical immunization" it seems possible WI/ROGUE was to administer the poisons brought to the Congo by Gottlieb.

The CIA, while accepting responsibility for plotting to kill Lumumba, disavows responsibility for his eventual murder. The Church Committee bought this line from the CIA and concluded the same in their report. Yet within the report and elsewhere on the record are events that belie that conclusion. For example, a cable from Devlin to Tweedy implies possible CIA foreknowledge of Lumumba’s escape which led to his death:

POLITICAL FOLLOWERS IN STANLEYVILLE DESIRE THAT HE BREAK OUT OF HIS CONFINEMENET AND PROCEED TO THAT CITY BY CAR TO ENGAGE IN POLITICAL ACTIVITY.... DECISION ON BREAKOUT WILL PROBABLY BE MADE SHORTLY. STATION EXPECTS TO BE ADVISED BY [unidentified agent] OF DECISION MADE.... STATION HAS SEVERAL POSSIBLE ASSETS TO USE IN EVENT OF BREAKOUT AND STUDYING SEVERAL PLANS OF ACTION. [23]

The Church Committee believed that one CIA cable seemed to indicate the CIA’s lack of foreknowledge of Lumumba’s eventual escape. But in another instance they cited this troubling passage, which indicates likely CIA involvement in his capture:

[STATION] WORKING WITH [CONGOLESE GOVERNMENT] TO GET ROADS BLOCKED AND TROOPS ALERTED [BLOCK] POSSIBLE ESCAPE ROUTE. [24]

According to contemporaneous cable traffic, the CIA was kept informed of Lumumba’s condition and movements during the period following his escape. Some authors believe that the CIA was directly involved in his capture. Andrew Tully acknowledges that "There were reports at the time that CIA had helped track him down," but adds, "there is nothing on the record to confirm this." However, nearly all authors agree that Lumumba was captured by Mobutu’s troops, and Mobutu was clearly, as Tully called him, "the CIA’s man" in the Congo.

By January of 1961, Devlin was sending urgent cables to CIA Director Allen Dulles stating that a [["refusal [to] take drastic steps at this time will lead to defeat of [United States] policy in Congo." [25] That particular cable was dated January 13, 1961. The very next day, Devlin was told by a Congolese leader that the captive Lumumba was to be transferred to a prison in Bakwanga, the "home territory" of his "sworn enemy." Three days later, Lumumba and two of his closest supporters were put on an airplane for Bakwanga. In flight, the plane was redirected to Katanga "when it was learned that United Nations troops were at the Bakwanga airport." Katanga claimed, on February 13, 1961, that Lumumba had escaped the previous day and died at the hands of hostile villagers. However, the U.N. conducted its own investigation, and concluded that Lumumba had been killed January 17, almost immediately upon arrival in Katanga. Other accounts vary. Some accounts indicated that on the plane, Lumumba and his supporters were so badly beaten that the Belgian flight crew became nauseated and locked themselves in the flight deck. Another account indicated that Lumumba was beaten "in full view of U.N. officials" and then driven to a secluded house and killed. But a contradictory version indicated that U.N. officers were not allowed in the area where the plane carrying Lumumba landed, and that the U.N. officials only had a glimpse at a distance of the prisoners when they disembarked. By all accounts, however, this was the last time any of the prisoners were seen in public alive.

In a bizarre footnote to this story, former CIA man John Stockwell wrote of a CIA associate of his who told him one night of his adventure in Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi), "driving about town after curfew with Patrice Lumumba’s body in the trunk of his car, trying to decide what to do with it." Stockwell added that his associate "presented this story in a benign light, as though he had been trying to help." [26] And in a similarly incriminating statement, CIA officer Paul Sakwa remembered that Devlin subsequently "took credit" for Lumumba’s assassination. [27]

In an open letter to CIA Director Admiral Stansfield Turner, Stockwell wrote:

Eventually he [Lumumba] was killed, not by our poisons, but beaten to death, apparently by men who had agency cryptonyms and received agency salaries. [28]

From the CIA’s own evidence, the CIA sought to entice Lumumba to escape protection. They then monitored his travel, assisted in creating road blocks, and when he was captured, encouraged his captors to turn him over to his enemies. The CIA had a strong relationship with Mobutu when Mobutu had the power to decide Lumumba’s fate. And then there are the admissions reported by Stockwell and Sakwa. How can anyone, in the light of such evidence, claim the CIA was not directly responsible for Lumumba’s murder?

Hammarskjold’s Last Flight

The CIA could not have been satisfied solely with the death of Lumumba. One of the barriers to completing the takeover of the Congo remained the United Nations, and more specifically, U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold.

Dag Hammarskjold’s heritage stemmed from that of a Swedish knight. Subsequent generations had served as soldiers and statesmen. It seemed only fitting that with such a heritage, Hammarskjold would be drawn to a life of governmental service. He grew up in the Swedish capital among a group of progressive economists, intellectuals, and artists. He sought out companions and mentors from these fields. But Hammarskjold was on a strong spiritual quest as well, seeking his own divine purpose and contemplating the sacrifices of others for the common good. He was an intensely private man who never married. Because of this, many assumed he must have been a homosexual. Hammarskjold always denied this, and once wrote a Haiku addressing his frustration at having to deal with this constant accusation:

Because it did not find a mate

they called

the unicorn perverted. [1]

Speaking four languages and having a reputation as an agile negotiator, Hammarskjold was a natural choice for the United Nations. Always gravitating toward roles of leadership, he came ultimately to serve in the highest position of that body during one of the most difficult periods in its existence.

When he took office, the United States was embroiled in virulent McCarthyism. His predecessor at the U.N. had bent over backwards to please American sponsors by expelling suspected communists from the ranks of the U.N. When Hammarskjold took his place, his first acts focused on rebuilding badly damaged morale among the U.N. workers. Once in office, he traveled the world seeking peace and reconciliation among warring factions. He felt that dispatching U.N. troops on peacekeeping missions was a necessary, if poor substitute for failed political negotiations. In 1958, Hammarskjold was unanimously reelected to a second five-year term as Secretary-General.

By far, Hammarskjold’s biggest challenge was the Congo. Hammarskjold understood the complexity of the political situation there and resisted moves that would put the people in that country at risk of exploitation. When Katanga seceded, the Soviets were furious that Hammarskjold didn’t send troops in to prevent the secession, and claimed Hammarskjold was siding with colonialists. Lumumba too lashed out at Hammarskjold for not responding in force. Hammarskjold’s hands were tied, however, by the American, British, French and Belgium factions which wanted to see Katanga secede in order to maintain access to the great mineral wealth there. But Hammarskjold did not give in completely to these non-native interests, and sent U.N. troops between the warring Congo and Katanga forces to see that one side did not annihilate the other. Hammarskjold had originally been impressed with Lumumba, but his opinion of him declined as Lumumba increasingly acted in an irresponsible manner. The country virtually fell apart in September when first Kasavubu (another Congo leader in the CIA’s pocket [29] ), then Lumumba, and ultimately Mobutu claimed to be the country’s leader. One of the few world leaders openly supporting Hammarskjold’s policy in the Congo was President John Kennedy.

Hammarskjold died in a plane crash sometime during the early morning hours of 8 September 1961. He was flying aboard the Albertina to the Ndola airport at the border of the Congo in Northern Rhodesia, where he was to meet with Tshombe to broker a cease-fire agreement. The pilot of the Albertina filed a fake flight plan in an attempt to keep Hammarskjold’s ultimate destination hidden. Despite this and other measures taken to preserve secrecy, less than 15 minutes into the flight the press was reporting that Hammarskjold was enroute to Ndola.

At 10:10, the pilot radioed the airport that he could see their lights, and was given permission to descend from 16,000 to 6,000 feet. Then the plane disappeared. It was found the next day, crashed and burnt at a site about ten miles from the airport. The unexplained downing of the plane gave rise immediately to rumors of attack and sabotage.

Two of Hammarskjold’s close associates, Conor Cruise O’Brien and Stuart Linner, had been targets of assassination attempts. Several attempts had been made in Elizabethville on O’Brien. And gunmen tried to lure Linner to Leopoldville, then under Kataganese control. One gunman even made his way into Linner’s office before being apprehended. Forces both inside and outside the Congo made clear that they did not approve of the U.N.’s handling of affairs there. U.N. forces were continually attacked. And Hammarskjold himself had received various threats. Because of this obvious animosity, it was no stretch for people to believe Hammarskjold’s death was no accident.

The origin of the plan to meet at Ndola was itself under dispute. O’Brien asserted in print on three different occasions that the location had been chosen by Lord Lansdowne. As one author noted:

He was doing more than accuse Lansdowne of not telling the truth. He was implying the Britisher was partly responsible for a journey that ended in disaster. [30]

The British government has always insisted the choice of Ndola was Hammarskjold’s. But the British were clearly working against Hammarskjold by siding with Katanga. The British colony of Northern Rhodesia also sent food and medical supplies to Katanga. Rhodesia’s Roy Welensky served as a media conduit for Tshombe. Clearly, the British had a motive to get rid of Hammarskjold, who stood in the way of Katanga’s independence, and therefore their denial regarding the choice of Ndola should be weighted accordingly. In fact, leaders from around the world accused Britain of being directly responsible. The Indian Express, India’s largest daily, wrote, "Never even during Suez have Britain’s hands been so bloodstained as they are now." Johshua Nkomo, President of the African National Democratic Party in Southern Rhodesia, said "The fact that this incident occured in a British colonial territory in circumstances which look very queer is a serious indictment of the British Government." The Ghanian Times ran an editorial headed "Britain: The Murderer." Note that this prophetic piece was written in 1961:

The history of the decade of the sixties is becoming the history of political and international murders. And one of the principal culprits in this sordid turn in human history is that self-same protagonist of piety—Britain.

Britain was involved, by virtue of her NATO commitments, in the callous murder of the heroic Congolese Premier, Patrice Lumumba. But Britain stands alone in facing responsibility for history’s No. 1 international murder—the murder of United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold. [31]

Due to public interest and obvious questions, both the British-contolled Northen Rhodesian government and the U.N. convened commissions to investigate the incident. Two of the earliest claims regarding the crash were given focus by both commissions: reports of a second plane, and reports of a flash in the sky near the airport. Seven different witnesses told the Rhodesian commission of a second plane in the vicinity of the Ndola airport. In Warren Commission-like fashion, the Rhodesian authorities waved away these sightings under various excuses. The only plane officially recorded to be in the vicinity was Hammarskjold’s, therefore the witnesses had to be wrong. But the airport was not using radar that night, and another plane could easily have been in the area. One witness chose not to talk to the Rhodesian authorities and went directly to the U.N.. He too had seen a second plane, following behind and slightly above a larger plane. After the plane crashed and exploded, he saw two Land Rover type vehicles rush at "breakneck speed" toward the site of the crash. A short time later, they returned. Asked why he hadn’t shared his account with the Rhodesians, the witness replied simply, "I do not trust them." The U.N. report theorized that perhaps people had seen the plane’s anti-collision beam and thought it represented a second plane. However, some of the witnesses claimed the second plane flew away from the first after the crash, negating that theory. [32] Earwitness evidence was also suggestive. Mrs. Olive Andersen heard three quick explosions at the time when the plane would have passed overhead. W. J. Chappell thought he heard the sound of a low-flying plane followed by the noise of a jet, followed later by three loud crashes and shots as if a canon was firing. [33]

Assistant Inspector Nigel Vaughan was driving on patrol that night about ten miles from the site of the crash. He told investigators that he saw a sudden light in the sky and then what seemed to be a falling object. But he placed the sighting an hour after the plane disappeared, and so his testimony is ignored. However, other witnesses also claimed to see a flash in the sky that night, including two police officers, one of which thought the sighting important enough to report to the airport.

Adding to suspicion of a broader plot was the fact that, despite the Albertina’s having announced its arrival at the airport, no alarm was raised when the plane did not land. In fact, Lord Alport sent the airport people home, claiming the Albertina’s occupants must have simply changed their mind and decided not to land there. No search and rescue operation was launched until well into the following morning.Later examinations of the bodies showed that Hammarskjold may well have survived the initial crash, although he had near-fatal if not fatal injuries. There was a small chance that had he been found in time, his life may have been saved.

Royal Rhodesian Air Force Squadron Leader Mussell told the U.N. commission that there were "underhand things going on" at that time in Ndola, "with strange aircraft coming in, planes without flight plans and so on." He also reported that "American Dakotas were sitting on the airfield with their engines running," which he imagined were likely "transmitting messages."

Beyond the strange circumstances surrounding the downing of the plane, the plane itself contained interesting, if controversial evidence. 201 live rounds, 342 bullets and 362 cartridge cases were recovered from both the crash site and the dead bodies. Bullets were found in the bodies of six people, two of whom were Swedish guards. The British Rhodesian authorities concluded that the ammunition had simply exploded in the intense heat of the fire, and just happened to shoot right into the humans present. But this contention was refuted by Major C. F. Westell, a ballistics authority, who said:

I can certainly describe as sheer nonsense the statement that cartridges of machine guns or pistols detonated in a fire can penetrate a human body. [34]

He based his statement on a large scale experiment that had been done to determine if military fire brigades would be in danger working near munitions depots. Other Swedish experts conducted and filmed tests showing that bullets heated to the point of explosion nonetheless did not achieve sufficient velocity to penentrate their box container. [35]

If someone aboard the plane fired the bullets found in these bodies, who would it have been? PG Lindstrom, in Copenhagen’s journal Ekstra Bladet, wrote that one of Tshombe’s agents in Europe told him that an extra passenger had been aboard who was to hijack the plane to Katanga. No evidence of an additional body was found in the wreckage, however.

Transair’s Chief Engineer Bo Vivring examined the plane and noted damage to the window frame in the cockpit area, as well as fiberglass in the radar nose cone, and concluded that these injuries were likely bullet holes. He told the Rhodesian commission months later, "I am still suspicious about these two specimens." [36]

In their final report, the Federal Rhodesian commission concluded that the incident was the result of pilot error, and denied any possibility that the plane was in any way sabotaged or attacked. The UN took a more cautious stance, declining to blame the pilot. But they were unable to pinpoint the cause, and refused to rule out the possibility of sabotage or attack. In contrast, the Swedish government, along with others carried the strong opinion that the plane had been shot from the ground or the air, or had been blown up by a bomb.

And there the matter lay, as far as the public was concerned. No one would know for sure. Some had suspicions. In a curious episode, Daniel Schorr once questioned whether the CIA was behind the murder. The question must be set in its original context.

In January of 1975, President Ford was hosting a White House luncheon for New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger, among others, when the subject of the Rockefeller commission came up. One of the Times’ editors questioned the overtly conservative, pro-military bent of the appointees. Ford explained that he needed trustworthy citizens who would not stray from the narrowly defined topics to be investigated so they wouldn’t pursue matters which could damage national security and blacken the reputation of the last several Presidents. "Like what?" came the obvious question, from A. M. Rosenthal. "Like assassinations!" said clumsy ex-Warren Commission member Ford, who added quickly, "That’s off the record!" But Schorr took the question to heart, and wondered what Ford was hiding. Shortly after this episode, Schorr went to William Colby, then CIA Director, and asked him point blank, "Has the CIA ever killed anybody in this country?" Colby’s reply was, "Not in this country." "Who?" Schorr pressed. "I can’t talk about it," deferred Colby. The first name to spring to Schorr’s lips was not Lumumba, Trujillo, or even Castro. It was Hammarskjold. [37]

Is there any evidence of British or CIA involvement in Hammarskjold’s death? Sadly, the answer is yes. Of both. In 1997, documents uncovered by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission indicated a conspiracy between the CIA and MI6 to remove Hammarskjold. Messages written on the letterhead of the South Africa Institute for Maritime Research (SAIMR), covering a period from July, 1960 to 17 September 1961, the date of Hammarskjold’s crash, discussed a plot to kill Hammarskjold named Operation Celeste. The messages, written by a commodore and a captain whose names were expunged by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, reference Allen Dulles. According to press reports, the most damning document refers to a meeting between CIA, SAIMR, and the British intelligence organizations of MI6 and Special Operations Executive, at which Dulles agreed that "Dag is becoming troublesome...and should be removed." Dulles, according to the documents, promised "full cooperation from his people." In another message, the captain is told, "I want his removal to be handled more efficiently than was Patrice [Lumumba]."

Later orders to the captain state:

Your contact with CIA is Dwight. He will be residing at Hotel Leopold II in Elizabethville from now until November 1 1961. The password is: "How is Celeste these days?" His response should be: "She’s recovering nicely apart from the cough." [38]

According to the documents, the plan included planting a bomb in the wheelbay of the plane so that when the wheels were retracted for takeoff, the bomb would explode. The bomb was to be supplied by Union Miniere, the powerful Belgian mining conglomerate operating in the Katanga province. However, a report dated the day of the crash records that the "Device failed on take-off, and the aircraft crashed a few hours later as it prepared to land." [39]

A British Foreign Officer spokesman suggested to the press that the documents were Soviet disinformation. [40] The documents were also dismissed as fakes by a former Swedish diplomat, but according to news reports, "they bear a striking resemblance to other documents emanating from SAIMR seven years ago ... These documents show the SAIMR masterminded the abortive 1981 attempt to depose Seychelles president Albert René. It was also behind a successful 1990 coup in Somalia." [41]

The reference to cooperation between MI5 and CIA is not farfetched either. British and American interests worked together to defeat Mossadegh in Iran. In his book that was originally banned in Britain for revealing too many state secrets, former MI5 officer Peter Wright described how William Harvey, the head of the CIA’s "Executive Action" programs, accompanied by CIA Counterintelligence Chief James Angleton, visited MI5 in 1961 to ask for help finding assassins. [42] And according to Paul Lashmar in his book Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1997, the British secretly aided in the overthrow of Sukarno in 1965, a coup for which the CIA bears a great deal of responsibility.

Brian Urquhart, a former U.N. Under-Secretary-General and the author of an extensive biography of Dag Hammarskjold, stated that "The documents seem to me to make no sense whatsoever." He praised Bishop Desmond Tutu for saying there was no verification for the authenticity of these documents. But Urquhart went too far when he said, "Even supposing there was any such conspiracy, which I strongly doubt, there is no conceivable way they could have got within any kind of working distance of Hammarskjold’s plane in time." [43] In fact, the plane was left unguarded for four hours. There was general security at the airport, but anyone who knew what they were doing would have no trouble gaining access to the plane. The cabin was secured, but the wheelbay, hydraulic compartments and heating systems were accessible. [44] Urquhart also contends that saboteurs would have attacked the wrong plane, as Lansdowne and Hammarskjold switched planes that day. But if the saboteurs were as sophisticated as the CIA was with Lumumba, that information would have been known in advance by the necessary parties. What if the plotters themselves occasioned the switch of the planes? Urquhart shows himself to be a man of limited imagination in this regard. Urquhart caps his comments by adding that he had seen "20 or 30 different accounts" over the years of how Hammarskjold was killed, and that "if one is true all the other 29 are false." In the words of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, "Does the word ‘duh’ mean anything to you?" There can be only one truth. Having 29 false leads would not negate the truth of the remaining one.

While Bishop Tutu conceded the documents may be disinformation, he added the following qualifier:

It isn’t something that is so bizarre. Things of that sort have happened in the past. That is why you can’t dismiss it as totally, totally incredible. [45]

In the Independent of 8/20/98, author Mary Braid wrote that "In 1992, ex-U.N. officials said mercenaries hired by Belgian, U.S. and British mining companies shot down the plane, as they believed their businesses would be hurt by Hammarskjold’s peace efforts." The key here is to understand that these assertions are not mutually exclusive. The CIA has shown its disdain for official government positions on more than several occasions, and has a long track record of working with private corporations to effect a foreign policy dictated more by business needs than political ones. In the Congo, we saw that the CIA apparently pursued a triple track. They planned poison, gun, and escape-capture-kill plans as they sought to remove Lumumba from the scene. If they were intent on getting rid of Hammarskjold, as the Truth Commission discoveries suggest, the CIA may have employed both bomb planters and mercenaries.

Has anyone ever claimed responsibility for Hammarskjold’s death? Surprisingly, the answer is yes. A longtime CIA operative claimed he personally shot down the plane.

Confessions of a Hitman

In 1976, Roland "Bud" Culligan sought legal assistance. After serving the CIA for 25 years, Culligan was angry. He had performed sensitive operations for the company and felt he deserved better treatment than to be put in jail on a phony bad check charge so the agency could "protect" him from foreign intelligence agents. He had been jailed since 1971, and now the agency was disavowing any connection with him. His personal assets had mysteriously vanished, and his wife Sara was being harassed. But Culligan had kept one very important card up his sleeve. He had kept a detailed journal of every assignment he had performed for the CIA. He had dates, names, places. And Culligan was a professional assassin.

Culligan sought the aid of a lawyer who in turn required some corroborative information. The lawyer asked Culligan to provide explicit details, such as who had recruited him into the CIA, who was his mutual friend with Victor Marchetti, and could he describe in detail six executive action (E.A.) assignments. Culligan answered each request. One of the executive actions he detailed was his assignment to kill Dag Hammarskjold. Culligan described first in general terms how he would receive assignments:

It is impossible, being here, to recall perfectly all details of past E.A.’s Each E.A. was unique and the execution was left to me and me alone. Holland [identified elsewhere as Lt. Gen. Clay Odum] would call, either by phone or letter memo. At times I would be "billed" by a fake company for a few dollars. The number to call was on the "bill." I have them all. I studied each man, or was introduced by a mutual friend or acquaintance, to dispell suspicion. I was not always told exactly why a man was subject to being killed. I believed Holland and CIA knew enough about matter to be trusting and I did my work accordingly.... By the time I was called in, the man had become a total loss to CIA, or had become involved in actual plotting to overthrow the U.S. Gov, with help from abroad. There were some exceptions.

...When an E.A. was planned, I was given all possible details in memo form, pictures, verbal descriptions, money, tickets, passports, all the time I needed for plan and set up. I and I alone called the final shot or shots.

Culligan matter-of-factly described five other EAs. But when he told of Hammarskjold, it was out of sequence and in a different tone than the other descriptions:

The E.A. involving Hammarskjold was a bad one. I did not want the job. Damn it, I did not want the job.... I intercepted D.H’s trip at Ndola, No. Rhodesia (now Zaire). Flew from Tripoli to Abidjian to Brazzaville to Ndola, shot the airplane, it crashed, and I flew back, same way.... I went to confession after Nasser and I swore I would never again do this work. And I never will.

Culligan did not want his information released. He only wanted to use it to pressure the CIA into restoring his funds, clearing his record, and allowing his wife and himself to live in peace. When this effort failed, a friend of Culligan’s pursued the matter by sending Culligan’s information to Florida Attorney General Robert Shevin.

Shevin was impressed enough by the documentation Culligan provided to forward the material along to Senator Frank Church, in which he wrote,

It is my sincere hope and desire that your Committee could look into the allegations made by Mr. Culligan. His charges seem substantive enough to warrant an immediate, thorough investigation by your Committee.

Culligan was scheduled to be released from prison in 1977. He wrote the CIA’s General Counsel offering to turn in his journal if he was released without any further complications. But once out of jail, Culligan found himself on the run continuously, fearing for his and his wife’s life. A friend continued to write public officials on Culligan’s behalf, saying:

There are forces that operate within our Government that most people do not even suspect exist. In the past, these forces have instituted actions that would be repugnant to the American people and the world at large. I have always wanted to see this situation handled quietly and honorably without a lot of publicity. Unfortunately, the agencies, bureaus, and services involved are devoid of honor. This story is extremely close to going public soon and when it does, I fear for the effect upon our Country and her position in the world community.

The story never did go public, until now. And this is only a piece of what Culligan had to say. [46] You can’t see all of what he had to say. These files remain restricted at the National Archives, withdrawn by the CIA, unavailable to researchers. Not even the Review Board could pry forth the tape Culligan made in jail detailing his CIA activities. And no wonder. Want to hear one of Culligan’s bombshells? In the list of Executive Actions Culligan detailed, three related to the Kennedy assassination. Culligan wrote that he was hired to kill three of the assassins who had participated in, as he called it, the "Dallas E.A." Apparently, the three were asking for larger sums to cover their silence. Culligan recruited them for a mission and told them to meet him in Guatemala. When they showed up, he killed all three.

Is Culligan to be believed? Why can’t we know for certain? Where are the leaders who are not afraid to confront the demons of the past, to genuinely seek out the truth about our history? Who will take this information and pursue it where it leads? Because no one pursued the truth about Lumumba at the time, and no one found the truth about Hammarskjold’s death, assassination remained a viable way to change foreign policy. Malcolm X, the two Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King fell prey to the same forces. When will the media serve the public, instead of the ruling elite, by finally reporting the truth about the assassinations of the sixties?

Notes

- ^ Gerard Colby with Charlotte Dennett, Thy Will Be Done (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), pp. 325-326.

- ^ Church Committee, Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975), p. 57, hereafter Assassination Plots.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 14.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 55

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 55.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 15.

- ^ Leonard Mosley, Dulles: A Biography of Eleanor, Allen, and John Foster Dulles and Their Family Network (New York: The Dial Press, 1978), pp. 462-463. From his notes, Mosley’s source for this appears to have been Richard Bissell.

- ^ John Marks, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate (New York, W. W. Norton & Co. Inc., 1979), p. 60.

- ^ Brian Urquhart, Hammarskjold (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), p. 451.

- ^ Andrew Tully, CIA: The Inside Story (New York: Crest Books, 1963), pp. 178, p. 184.

- ^ Hammarskjold was later to write that policy in the Congo "flopped" and cited as two defeats "the dismissal of Mr. Lumumba and the ousting of the Soviet embassy." Urquhart, p. 467.

- ^ John Prados, Presidents’ Secret Wars (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996), p. 234.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 23.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 29.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 32.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p.38n1.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 39.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 45.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 44.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 46.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 46.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 48.

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 48

- ^ Assassination Plots, p. 49.

- ^ John Stockwell, In Search of Enemies (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1978), p. 105.

- ^ Richard D. Mahoney, JFK: Ordeal in Africa (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 67.

- ^ Mahoney, p. 71, citing the letter as published in the International Herald-Tribune of April 25, 1977.

- ^ Urquhart, p. 27.

- ^ William Blum, Killing Hope (Monroe: Common Courage Press, 1986), p. 158.

- ^ Arthur Gavshon, The Mysterious Death of Dag Hammarskjold (New York: Walker and Company, 1962), p. 167. Gavshon was, according to the biography on the back flap of his book, a "veteran diplomatic correspondent for one of the world’s biggest new agencies and from his London vantage point has had access to the confidential information known to the diplomats and governments riding the dizzying Congolese merry-go-round."

- ^ Gavshon, p. 50.

- ^ Gavshon, p. 237.

- ^ Gavshon, p. 17.

- ^ Gavshon, p. 58.

- ^ Gavshon, p. 58.

- ^ Gavshon, p. 57.

- ^ Daniel Schorr, Clearing the Air (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977), pp. 143-145.

- ^ Mail & Guardian (of Johannesburg, South Africa), 8/28/98.

- ^ Mail & Guardian, 8/28/98.

- ^ The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, 8/20/98.

- ^ Mail & Guardian, 8/28/98.

- ^ Peter Wright, Spy Catcher (New York: Dell, 1988), pp. 203-204.

- ^ Anthony Goodman, Reuters, 8/19/98.

- ^ Gavshon, p. 8.

- ^ The Atlanta Constitution and Journal, 8/22/98.

- ^ For more information on Culligan, see Kenn Thomas’ interview of Lars Hansson in Steamshovel Press #10, 1994.