Difference between revisions of "Black legend"

(enemy image) |

m (clean) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

* Accidentality of merit. Black legends tend to minimize the merits they cannot fully erase or hide, by either portraying them as "mere luck", opportunism or, at best, as isolated qualities. | * Accidentality of merit. Black legends tend to minimize the merits they cannot fully erase or hide, by either portraying them as "mere luck", opportunism or, at best, as isolated qualities. | ||

* Obligatory moral actions. When a noble action by the subject cannot be denied, it is somehow presented as done out of self-interest or out of necessity. | * Obligatory moral actions. When a noble action by the subject cannot be denied, it is somehow presented as done out of self-interest or out of necessity. | ||

| − | * Natural moral inferiority and irredeemable character. The black legend has a final tone in which no hope of improvement is given, for the defects have been there from the beginning and cannot be overcome due to, usually, moral weakness. | + | * Natural moral inferiority and irredeemable character. The black legend has a final tone in which no hope of improvement is given, for the defects have been there from the beginning and cannot be overcome due to, usually, moral weakness. |

Narrations of black legends tend to include: | Narrations of black legends tend to include: | ||

Latest revision as of 12:18, 1 November 2022

(enemy image) | |

|---|---|

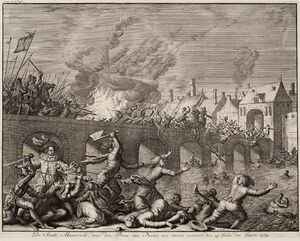

Spaniard feeding an Indian baby to his dogs | |

A black legend is a historiographical phenomenon in which a sustained trend in historical writing of biased reporting and introduction of fabricated, cherry picked, exaggerated and/or decontextualized facts is directed against particular persons, nations or institutions with the intention of creating a distorted and uniquely inhuman image of them while hiding their positive contributions to history.

Black legends propaganda often has some of its basis in real events, genuine atrocities and cruelty, but it often employed with lurid and exaggerated depictions of violence, while ignoring similar behaviour by other powers.

Black legends have been perpetrated against many nations and cultures, usually as a result of propaganda and xenophobia. For example, the "Spanish Black Legend" (La leyenda negra española) is the theory that anti-Spanish political propaganda, whether about Spain, the Spanish Empire or Hispanic America, was sometimes "absorbed and converted into broadly held stereotypes" that assumed that Spain was "uniquely evil".[1]

Contents

Some Causes

- The combined propaganda attacks and efforts of most smaller powers of the time, as well as defeated rivals.

- The propaganda created by the many rival power factions within the empire itself against each other as part of their struggle to win more power.

- The self-criticism of the intellectual elite, which tends to be larger in larger empires.

- The need of the new powers consolidated during the empire's life or after its dissolution to justify their new prevalence and the new order.

The black legend tends to fade once the next great power is established or once enough time has gone by.

Common elements of black legends

The defining feature of a black legend is that it has been fabricated and propagated intentionally. Black legends also tend to share certain additional elements:[2]

- Permanent decadence. Black legends tend to portray their subjects as being in a permanent estate of degeneration.

- Degenerated or polluted version of something else. The subject is portrayed as a degenerated form of another, usually another civilization, nation, religion, race or person, who represents the true, pure and noble form of whatever the subject of the black legend should have been, and that tends to coincide with whoever is building the legend.

- Accidentality of merit. Black legends tend to minimize the merits they cannot fully erase or hide, by either portraying them as "mere luck", opportunism or, at best, as isolated qualities.

- Obligatory moral actions. When a noble action by the subject cannot be denied, it is somehow presented as done out of self-interest or out of necessity.

- Natural moral inferiority and irredeemable character. The black legend has a final tone in which no hope of improvement is given, for the defects have been there from the beginning and cannot be overcome due to, usually, moral weakness.

Narrations of black legends tend to include: Strong pathos, combined with a narrative that is easy to follow and emotionally loaded, created by:

- Detailed, gruesome and morbid descriptions of torture and violence, which in many cases does not seem to serve any practical purpose.

- Sexual elements, either extreme sexual depravity or repression or more often a combination of both.

- Ignorance. Lack of intellectual refinement or independence.

- Greed, materialism, accusations of disrespect for sacred, or very important institutions or moral rules.

- A theme, usually greed, cruelty, sadism or bigoty, that constructs a consistent character and remains stable through the legend, even if the specific "proofs" to support it may change or even become opposite to the initial ones.

- Simplicity of elements, often repetition of the same anecdotes or scenarios with different variations. Motivations for actions are often offered, but they are either one single motivation or two, negative, clear cut, and constant.

The Spanish Black Legend

The Black Legend (La leyenda negra), or the Spanish Black Legend, is a theorised historiographical tendency consisting of anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic propaganda. Its proponents claim that its roots date back to the 16th century, when it was originally a political and psychological weapon that was allegedly used by Spain's northern European rivals in order to demonize the Spanish Empire, its people and culture, minimize Spanish discoveries and achievements, and counter its influence and power in world affairs.

The overlap of the period of splendour of the Spanish Empire with the introduction of the printing press in England and Germany, allowed the propaganda of such colonial and religious rivals to spread faster and wider than ever before and persist in time long after the disappearance of the empire. [3]

One reason for its durability is the unique characteristics of the colonial wars of the early contemporary period and the need of new colonial powers to legitimize claims in now independent Spanish colonies, as well as the unique and new characteristics of the British Empire that succeeded it.[4]

This 17th-century propaganda found its basis in real events during the Spanish conquest of the Americas, which did involve atrocities, but it often employed lurid and exaggerated depictions of violence, while ignoring similar behaviour by other powers.[5]

The conquest of the Americas

During the three-century European colonization of the Americas, atrocities and crimes were committed by all European nations according to both contemporary opinion and modern moral standards. Spain's colonization also involved massacres, murders, sexual slavery and other grotesque abuses of human rights, especially in the early years, following the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean and the conquest of the Aztec and Incas empires.

However, Spain was the first in recorded history to pass laws for the protection of indigenous peoples. As early as 1512, the Laws of Burgos regulated the behavior of Europeans in the New World forbidding the ill-treatment of indigenous people and limiting the power of encomenderos—landowners who received royal grants to recruit remunerated labor. The laws established a regulated regime of work, pay, provisioning, living quarters, hygiene, and care for the natives in a reasonably humanitarian spirit. The regulation prohibited the use of any form of punishment by the landowners and required that the huts and cabins of the Indians be built together with those of the Spanish. [6] These New Laws represented a humanitarian effort that was not enough to dissuade rebellions, like that of Gonzalo Pizarro in Perú. However, this body of legislation represents one of the earliest examples of humanitarian laws of modern history.[7] Although these laws were not always followed, they reflect the conscience of the 16th century Spanish monarchy about native rights and well-being, and its will to protect the inhabitants of Spain's territories.

The ill-treatment of Amerindians, which would later occur in other European colonies in the Americas, was used in the works of competing European powers in order to foster animosity against the Spanish Empire. De las Casas' work was first cited in English in the 1583 The Spanish Colonie, or Brief Chronicle of the Actes and Gestes of the Spaniards in the West Indies, at a time when England was preparing for war against Spain in the Netherlands.

All European powers which colonized the Americas, including England, Portugal and the Netherlands, ill-treated indigenous peoples. Colonial powers have also committed genocide in Canada, the United States, and Australia.

War with the Netherlands

The victories and atrocities of the Castilian nobleman Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, contributed to anti-Spanish propaganda. Sent in August 1567 to counter political unrest in a part of Europe where printing presses encouraged a variety of opinions (especially against the Catholic Church), Alba seized control of the publishing industry; several printers were banished, and at least one was executed. Booksellers and printers were prosecuted and arrested for publishing banned books, many of which were part of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

In 1568 Alba had prominent Dutch nobles executed in Brussels' central square, sparking anti-Spanish sentiment. In October 1572, after Orange forces captured the city of Mechelen, its lieutenant attempted to surrender when he heard that a larger Spanish army was approaching. Despite efforts to placate the troops, Fadrique Álvarez de Toledo (son of the governor of the Netherlands and commander of the duke's troops) allowed his men three days to pillage the city; Alba reported to King Philip II that "not a nail was left in the wall". A year later, magistrates were still attempting to retrieve church artifacts which Spanish soldiers had sold elsewhere.[8][9]

In November and December 1572, with the duke's permission, Fadrique had residents of Zutphen and Naarden locked in churches and burnt to death.[10] In July 1573, after a six-month siege, the city of Haarlem surrendered. The garrison's men (except for the German soldiers) were drowned or had their throats cut by the duke's troops, and eminent citizens were executed. More than 10,000 Haarlemers were killed on the ramparts, nearly 2,000 burned or tortured, and double that number drowned in the river.[11]

After numerous complaints to the Spanish court, Philip II decided to change policy and relieve the Duke of Alba. Alba boasted that he had burned or executed 18,600 persons in the Netherlands,[12] in addition to the far greater number he massacred during the war, many of them women and children; 8,000 persons were burned or hanged in one year, and the total number of Alba's Flemish victims can not have fallen short of 50,000.[13]

The propaganda created by the Dutch Revolt during the struggle against the Spanish Crown can also be seen as part of the Black Legend. The depredations against the Indians that De las Casas had described, were compared to the depredations of Alba and his successors in the Netherlands. The Brevissima relacion was reprinted no less than 33 times between 1578 and 1648 in the Netherlands (more than in all other European countries combined).[14] The Articles and Resolutions of the Spanish Inquisition to Invade and Impede the Netherlands accused the Holy Office of a conspiracy to starve the Dutch population and exterminate its leading nobles, "as the Spanish had done in the Indies."[15] Marnix of Sint-Aldegonde, a prominent propagandist for the cause of the rebels, regularly used references to alleged intentions on the part of Spain to "colonize" the Netherlands, for instance in his 1578 address to the German Diet.

No genetic imprint from rapes

The memory of the large scale rape of local women by Spanish soldiers lives on in Belgium and Netherlands to such extent that it is popularly believed that their genetic imprint can be still seen today, and that most men and women with dark hair in the area descend from children conceived during those rapes. A modern genetic study[16] found no greater Iberian genetic component in the areas occupied by the Spanish army than in surrounding areas of northern France, and concluded that the genetic impact of the Spanish occupation, if any, must have been too small to survive until the present era.

Dr. Larmuseau, the maker of the study, considers the persistence of the belief in a Spanish genetic contribution in Flanders to be the fruit of the use of Black Legend tropes in the construction of Dutch and Flemish national identities in the 16th-19th century, leading to the prominence of the stereotype of the cruel Spanish soldier in the collective memory.

In an interview with a local newspaper, Dr. Larmuseau compared the persistence in popular memory of the actions of the Spanish with the lesser attention given to the Austrians, the French and the Germans who also occupied the Low Countries and participated in violence against their inhabitants.[17]

An example

| Page name | Description |

|---|---|

| China/Black legend |

References

- ↑ Maltby, William B (1996). "The Black Legend". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1 \: 346–348.

- ↑ Barea, Roca; Elvira, María (2016), Imperiofobia y leyenda negra. Roma, Rusia, Estados Unidos y el Imperio español [Imperiophobia and black legends. Rome, Russia, United States and the Spanish Empire] (in Spanish), Madrid: Siruela,

- ↑ Murry, G. "Tears of the Indians" or Superficial Conversion?: José de Acosta, the Black Legend, and Spanish Evangelization in the New World. The Catholic Historical Review. pp. 29–51.

- ↑ Marías, Julián (2006; primera edición 1985). España Inteligible. Razón Histórica de las Españas. Alianza Editorial. ISBN 84-206-7725-6.

- ↑ http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A11075070/LitRC?sid=googlescholar

- ↑ https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006147282

- ↑ https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2012/12/the-laws-of-burgos-500-years-of-human-rights/

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=bm_uS_K_jaEC&pg=PA226

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20120118023741/http://www.elsen.eu/docs/vp091/elsen-veiling91-lasser-historischkader.pdf

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20110927032644/http://www.naarden.nl/index.php?simaction=content&mediumid=4&pagid=201&stukid=345

- ↑ The Public and Private History of the Popes of Rome, Vol. 1: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, Including the History of Saints, Martyrs, Fathers of the Church, Religious Orders, Cardinals, Inquisitions, Schisms, and the Great Reformers |date=1846 |publisher=T. B. Peterson |page=249

- ↑ http://necrometrics.com/pre1700a.htm#Ne1566

- ↑ Sharp Hume, Martín Andrew. The Spanish People: Their Origin, Growth and Influence. p. 372.

- ↑ Schmidt, p. 97

- ↑ Schmidt, p 112

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.23409

- ↑ https://www.larazon.es/sociedad/ciencia/los-holandeses-morenos-y-bajitos-no-tienen-sangre-espanola-LH17453787/