Lipid nanoparticle

(medical technology, nanomaterial) | |

|---|---|

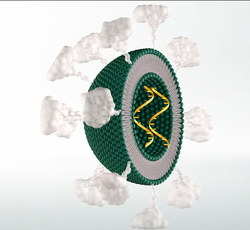

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). There is only one phospholipid layer because the bulk of the interior of the particle is composed of lipophilic substance. Payloads such as modified RNA, RNA vaccine or others can be embedded in the interior, as desired. Optionally, targeting-molecules such as antibodies, cell-targeting peptides, and/or other drug molecules can be bound to the exterior surface of the SLN. | |

| Start | 2018 |

| First used in 2018, LNPs are now used in modified-RNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. | |

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) is a pharmaceutical drug delivery system discovered as recently as 2018.

From late 2020, several mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 use LNPs as their drug delivery system, including both the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine and the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines.[1] Moderna uses its own proprietary ionizable cationic lipid called SM-102, while Pfizer and BioNTech licensed an ionizable cationic lipid called ALC-0315 from the company Acuitas.[2]

Contents

Lipid

A lipid is a type of organic molecule found in living things. It is oily or waxy. Fats are made from lipid molecules. Lipids are a group of naturally occurring molecules that include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E, and K), glycerides, phospholipids, and others. Lipids are classified as simple and complex. Examples of complex molecules could be steroids or phospholipids. A very important biological function of lipids is as lipid bilayers, the basis of many cell membranes. Another function of lipids is to serve as an energy reserve. The main biological functions of lipids include storing energy, signalling, and acting as components of cell membranes.[3]

History

A significant obstacle to using LNPs as a delivery vehicle for nucleic acids is that in nature, lipids and nucleic acids both carry a negative electric charge—meaning they do not easily mix with each other.[4] While working at Syntex in the mid-1980s,[5] Philip Felgner pioneered the use of artificially-created cationic lipids (positively-charged lipids) to bind lipids to nucleic acids in order to transfect the latter into cells.[6] However, by the late 1990s, it was known from in vitro experiments that this use of cationic lipids had undesired side effects on cell membranes.[7]

During the late 1990s and 2000s, Pieter Cullis of the University of British Columbia developed ionizable cationic lipids which are "positively charged at an acidic pH but neutral in the blood."[2] Cullis also led the development of a technique involving careful adjustments to pH during the process of mixing ingredients in order to create LNPs which could safely pass through the cell membranes of living organisms.[4][8]

From 2005 into the early 2010s, LNPs were investigated as a drug delivery system for small interfering RNA (siRNA) drugs.[2] In 2009, Cullis co-founded a company called Acuitas Therapeutics to commercialize his LNP research; Acuitas worked on developing LNPs for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals's siRNA drugs.[9] In 2018, the FDA approved Alnylam's siRNA drug Onpattro (patisiran), the first drug to use LNPs as the drug delivery system.[1][2]

Moderna and BioNTech

From late 2020, several mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 use LNPs as their drug delivery system, including both the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine and the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines.[1] Moderna uses its own proprietary ionizable cationic lipid called SM-102, while Pfizer and BioNTech licensed an ionizable cationic lipid called ALC-0315 from Acuitas.[2]

The synthetic ionizable lipid in the Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is believed to have a half-life of around 20-30 days in humans.[10]

Philadelphia study

A December 2021 study from Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia showed that injection of the LNPs used by BioNTech and Modern leads to rapid and powerful inflammatory responses. This could explain their potent adjuvant effect. Intranasal administration with higher doses of LNPs resulted in a significant mortality rate.[11][12]

The mechanism of action of the mRNA component is modified in such a way that it reduces the activation of sensors of the innate immune system. People who received the vaccine often had typical acute side effects of inflammation, such as pain, swelling, and fever. The inflammatory responses triggered solely by the LNPs or together with mRNAs were independent of the route of administration. They are therefore responsible for a range of extremely serious side effects.[11]

Threats against researcher

German Cell biologist Vanessa Schmidt-Krüger explained in detail what the Philadelphia researchers concluded in two videos already at end of 2020[13]. After the explanations presented a very uncomfortable truth for the vaccine producers, the scientist and her family were severely threatened. She then withdrew almost all of the videos, explaining:

In order to avert harm to myself and the people who are important to me, I feel compelled to delete informational videos. My intention was to publish my private opinion on the basis of scientific facts and to convey my knowledge and experience as a cell biologist to a broad audience in an understandable way. I would have gladly continued my work and published my other videos. I would be happy if it becomes possible again in the future.[14]

Patent litigation

On March 10, 2023, U.S. District Judge Mitchell Goldberg rejected a bid by Moderna to dismiss some of the patent infringement claims brought against the company by Arbutus Biopharma and its partner, Genevant Sciences.[15][16]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5906799

- ↑ Jump up to: a b c d e https://cen.acs.org/pharmaceuticals/drug-delivery/Without-lipid-shells-mRNA-vaccines/99/i8

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2674711

- ↑ Jump up to: a b https://qz.com/1948132/the-first-covid-19-vaccines-have-changed-biotech-forever/

- ↑ {https://library.ucsd.edu/sdta/transcripts/felgner-phil_19970722.html

- ↑ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Pharmaceutical_Perspectives_of_Nucleic_A/XKgb-xbnTlUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA275&printsec=frontcover

- ↑ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Liposomes_in_Gene_Delivery/e2bMWl2NZ_4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA191&printsec=frontcover

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5498813

- ↑ https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/covid-19-vancouvers-acuitas-therapeutics-a-key-contributor-to-coronavirus-solution

- ↑ https://tkp.at/2021/12/09/wesentliche-daten-fehlen-bei-bedingter-biontech-pfizer-zulassung-in-eu-alc/

- ↑ Jump up to: a b https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004221014504

- ↑ https://tkp.at/2021/12/22/so-verursachen-lipid-nanopartikel-in-gentechnik-impfstoffen-durch-entzuendungen-schwere-nebenwirkungen/

- ↑ https://tkp.at/2021/01/03/gefahren-ausgehend-von-lipidnanopartikeln-in-mrna-impfstoffen/

- ↑ https://tkp.at/2021/01/03/gefahren-ausgehend-von-lipidnanopartikeln-in-mrna-impfstoffen/

- ↑ Stieber, Z. (2023, March 13). Judge Rejects Request From Moderna, Moving Key COVID-19 Vaccine Case to Discovery. The Epoch Times. http://archive.today/2023.03.13-173504/https://www.theepochtimes.com/judge-rejects-request-from-moderna-moving-key-covid-19-vaccine-case-to-discovery_5119082.html

- ↑ Goldberg, M. (2023). Case 1:22-cv-00252-MSG Document 64. Document Cloud; United States District Court for the District of Delaware. https://web.archive.org/web/20230316161451/https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23706145/moderna-covid-19-opinion.pdf

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here