Simon Mann

Simon Francis Mann (born 26 June 1952) is a British mercenary and former British SAS officer. He had been serving a 34-year prison sentence in Equatorial Guinea for his role in a failed coup d'état in 2004, before receiving a presidential pardon on humanitarian grounds on 2 November 2009.[1] Simon Mann was extradited from Zimbabwe to Equatorial Guinea on 1 February 2008,[2] having been accused of planning a coup d'état to overthrow the government by leading a mercenary force into the capital Malabo in an effort to overthrow President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. Charges in South Africa of aiding a coup in a foreign country were dropped on 23 February 2007,[3] but the charges remained in Equatorial Guinea, where he had been convicted in absentia in November 2004. He lost an extradition hearing to Equatorial Guinea after serving three years of a four-year prison sentence in Zimbabwe for the same crimes and being released early on good behaviour.[4] Upon Mann's arrival in Equatorial Guinea for his trial in Malabo, Public Prosecutor Jose Olo Obono said that Mann would face three charges – crimes against the head of state, crimes against the government, and crimes against the peace and independence of the state.[5] On 7 July 2008, he was sentenced to 34 years and four months in prison by a Malabo court.[6] He was released on 2 November 2009, on humanitarian grounds.[7][8]

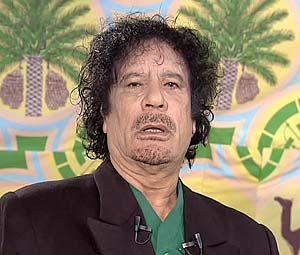

In September 2013, the Daily Telegraph reported in an article entitled "Secret MI6 plot to help Colonel Gaddafi escape Libya revealed" that - during the 2011 NATO bombing campaign in Libya - Andrew Mitchell, then International Development Secretary, was dispatched to build covert contacts with the controversial regime in Equatorial Guinea. The Cabinet Office and MI6 had "prepared an exit strategy for Gaddafi in case it was necessary to strike a deal and to end the conflict," and Equatorial Guinea, "oil-rich but awesomely corrupt", was selected for Colonel Gaddafi "as a prospective retirement home." Although Britain has no bilateral links with Equatorial Guinea, contributing only small amounts in aid, Mr Mitchell "was able to assist the officials tasked with these delicate contingency plans, helping make the necessary contacts in the capital, Malabo, and elsewhere."

Ultimately, Colonel Gaddafi was killed by rebels as he tried to flee Sirte on 20 October 2011. It was believed that he was heading for the border of Niger at the time of his death. His 50-car convoy was attacked by NATO airplanes before rebels attacked on the ground. Colonel Gaddafi was tortured before he was killed. It has previously been reported that Colonel Gaddafi was being escorted by a group of South African mercenaries when he came under attack. One of the South Africans subsequently claimed that they believed the escape attempt was operating with tacit support from Western countries. However, the group drove into an ambush with sustained air strikes from French warplanes and ground attacks from rebel fighters.[9]

Equatorial Guinea gained notoriety after an unsuccessful coup attempt in 2004, led by the old Etonian Simon Mann and involving Margaret Thatcher's son Mark Thatcher. The "Wonga Coup" failed after a group of mercenaries were arrested in Zimbabwe shortly before launching an attack.[10]

Although the ICC had issued an arrest warrant for Colonel Gaddafi, Equatorial Guinea’s refusal to recognise the court’s authority would have kept Colonel Gaddafi outside its reach. It is believed that some of the mercenaries involved in the Equatorial Guinea coup were also involved in the attempt to extract Gaddafi.[11][12]

Contents

Early life

Simon Mann's father, George Mann, captained the England cricket team in the late 1940s and was an heir to a stake in the Watney Mann brewing empire that closed in 1979, having been acquired by Grand Metropolitan (which, in 1997, became Diageo plc on its merger with Guinness). His mother is South African.

Military career

After leaving Eton College, Simon Mann trained to be an officer at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, and was commissioned into the Scots Guards on 16 December 1972. By 1976 he held the rank of Lieutenant. He later became a member of the Special Air Service (SAS) and served in Cyprus, Germany, Norway and Northern Ireland before leaving the forces in 1985. He was re-called to action from the reserves for the Gulf War.

Post-military career

Simon Mann then entered the field of computer security; however, his interest in this industry lapsed when he returned from his service in the Gulf and he entered the oil industry to work with Tony Buckingham. Buckingham also had a military background and had been a diver in the North Sea oil industry before joining a Canadian oil firm. In 1993, UNITA rebels in Angola seized the port of Soyo, and closed its oil installations. The Angolan government under Jose Eduardo dos Santos sought mercenaries to seize back the port and asked for assistance from Buckingham who had by now formed his own company.[13]

Sandline International

Simon Mann went on to establish Sandline International with fellow ex-Scots Guards Colonel Tim Spicer in 1996. The company operated mostly in Angola and Sierra Leone, but in 1997 Sandline received a commission from the government of Papua New Guinea to suppress a rebellion on the island of Bougainville and the company came to international prominence, but received much negative publicity following the Sandline affair. Sandline International announced the closure of the company's operations on 16 April 2004. In an interview on the Today Programme, Mann indicated that the operations in Angola had netted more than £10,000,000.

Equatorial Guinea coup attempt

On 7 March 2004, Mann and 69 others were arrested in Zimbabwe when their Boeing 727 was seized by security forces during a stop-off at Harare's airport to be loaded with £100,000 worth of weapons and equipment. The men were charged with violating the country's immigration, firearms and security laws and later accused of engaging in an attempt to stage a coup d'état in Equatorial Guinea. Meanwhile eight suspected mercenaries, one of whom later died in prison, were detained in Equatorial Guinea in connection with the alleged plot. Mann and the others claimed that they were not on their way to Equatorial Guinea but were in fact flying to the Democratic Republic of Congo in order to provide security for diamond mines owned by JFPI Corporation. Mann and his colleagues were put on trial in Zimbabwe, and, on 27 August, Mann was found guilty of attempting to buy arms for an alleged coup plot and sentenced to 7 years imprisonment.[14] 66 of the others were acquitted.[15]

On 25 August 2004, Sir Mark Thatcher, son of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, was arrested at his home in Cape Town, South Africa. He eventually pleaded guilty (under a plea bargain) to negligently supplying financial assistance for the plot.[16] The 14 men in the mercenary advance guard that were caught in Equatorial Guinea were sentenced to jail for 34 years.[17]

Among the advance guard was Nick du Toit who claimed that he had been introduced to Thatcher by Mann. Investigations later revealed in Mann's holdings' financial records that large transfers of money were made to Nick du Toit, as well as approximately US$2 million coming in from an untraceable and unknown source. On 10 September Mann was sentenced to seven years in jail. His compatriots received one-year sentences for violating immigration laws and their two pilots got 16 months. The group's Boeing 727 was seized, as well as the US$180,000 that was found on board the plane.

Charges dropped and extradition

On 23 February 2007, charges were dropped against Mann and the other alleged conspirators in South Africa. Mann remained in Zimbabwe, where he was convicted of charges from the same incident. On 2 May 2007 a Zimbabwe court ruled that Mann should be extradited to Equatorial Guinea to face charges, although the Zimbabweans promised that he would not face the death penalty. His extradition was described as the "oil for Mann" deal, in reference to the large amounts of oil that Mugabe has managed to secure from Equatorial Guinea. The Black Beach prison in Equatorial Guinea, where Mann was sent, is notorious for its bad conditions. Mann lost his last appeal against the decision to extradite him.[18] In a last-ditch effort on 30 January 2008, Mann tried to appeal the judgment to the Zimbabwean Supreme Court.[19] The following day, Mann was deported to Equatorial Guinea in secret, leading to claims by his lawyers that the extradition was hastened to defeat the possibility of appeal to the Supreme Court.[20][21]

Response by UK Parliamentarians

Concern for Mann's plight was raised in the UK Parliament in the year of his arrest in Zimbabwe by three Conservative Members of Parliament.[22][23][24] During the two years after the government of Equatorial Guinea applied for his extradition, three further Conservative Party MPs submitted written questions.[25][26][27]

There was a request that the United States administration, which had access to Simon Mann in Black Beach Prison on 6 February 2008, exert its influence "to secure [his] safe return".[28] UK officials were granted access to him on 12 February 2008.[29] Labour and other parties expressed little concern about Mann or the others. The only non-Conservative Party MP to submit a question in Parliament about him was Vince Cable,[30] although an Early Day Motion about his treatment in prison received some cross-party support.[31]

On 8 March 2008, Channel 4 in the UK won a legal battle to broadcast an interview with Mann in which he named British political figures, including Ministers, alleged to have given tacit approval to the coup plot.[32] In testimony he spoke frankly about the events leading to the botched attempt to topple Equatorial Guinea's president.

Despite their charges being unrelated, Simon Mann was tried alongside six Progress Party of Equatorial Guinea activists being held on weapons charges, including opposition leader Severo Moto's former secretary Gerardo Angüe Mangue.[33] On 7 July 2008, Mann was sentenced by the Equatorial Guinea court to more than 34 years in jail.

Release

On 2 November 2009 he was given "a complete pardon on humanitarian grounds" by President Teodoro Obiang Nguema. He was back in England by 6 November.

Interview with Simon Mann

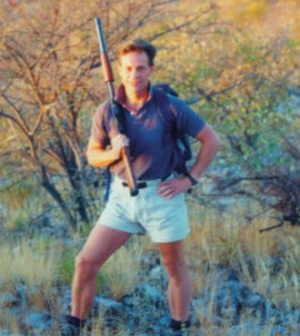

Simon Mann is a British mercenary, most famous for his failed 2004 coup attempt against Teodoro Obiang, president of Equatorial Guinea. An ex-Special Forces soldier, Simon co-founded with Eeben Barlow the private military company Executive Outcomes, which at its height in the mid-90s ran two African wars, using oil money to fund a full-on air force and thousands of private soldiers.

In 2004, after pocketing millions fighting rebels in Angola and, he says, protecting a free election in Sierra Leone, Simon Mann’s luck ran out. He’d been hired to fly to Equatorial Guinea with 69 South African heavies, capture the airport and escort an opposition leader to the presidential palace. During a layover in Zimbabwe to collect guns and refuel, he was busted.

He ended up in Chikurubi Prison, one of Zimbabwe’s nastiest, before being extradited to Equatorial Guinea four years later. There he spent a year and a half in solitary at Black Beach prison, one of Africa’s nastiest, before being pardoned. Simon Mann has written a book about his adventures, there’s a movie in the pipeline and he’s working on a novel he wrote in jail. Between all that, he spoke to me about coups, spies and kick-starting the Iraq War.

VICE: The world of mercenaries is a pretty murky one – how did you get to the top of it?

- Simon Mann: Not on purpose. I left the SAS in 1992 and joined an oil company that had one project in Soyo, Angola. I went into the office one day and they said, "This is it; we’re fucked." UNITA rebels had gone back to war, against the treaties they’d signed, and had captured Soyo, ending our business. I suggested that we retake the town. Two months later, we did. Then the government asked us to take the whole country back. We said "Yep, but it’s going to cost you." We eventually had 2,000 men under contract and a turnover of £12.5 million every nine months.

A nice little earner. Then you went to Sierra Leone?

- Yeah. The Sierra Leoneans asked us to go diamond mining there, but there was a problem: a really bad war. So we told the president we'd help him if we could get help applying for a legal diamond concession. It cost us millions to keep fighting, but our money was coming from the war in Angola, which is what made us different from other warlords – we were reinvesting in Africa. Just as we were leaving, the president asked us to stay and secure the election, so it was – not the UN – who protected that election. We kept asking, "What kind of fucking mercenaries are we?" We were the nicest, most well-behaved bunch ever.

Weren’t you also asked to help kick start the Iraq War in 2002?

- Yes. A guy called David Hart told me he was friends with the American neocons and asked me to come up with ideas to get the war kicked off. The first was to pick an Iraqi city away from Baghdad, go there with a rebel force made up of 6,000 Iraqi émigrés, take the city, then say, "Yah boo" to Saddam. That would have forced him to come get us and be zapped on the road by the UK and US, or let the flag of rebellion spread.

- The second was far more criminal. We wanted to buy an old rust-bucket ship, sail it to Karachi, load up secretly with some weapons-grade uranium, or whatever, then sail it into the Gulf with a motley crew, including me. We’d then leak our presence to the Saudis, get the navy to intercept us, sink their ship – hopefully without killing anyone – then sail into Basra. The world would have gone nuts and we’d have had an excuse for war in Iraq.

That’s pretty scandalous.

- Well, yes. We actually got feedback from Number 10, via David Hart, that they liked the ideas, but not me. I believed him.

And then there was the coup attempt in Equatorial Guinea.

- Yeah. I was recruited by "The Boss", who told me about President Obiang, his human rights abuses and how much oil he had, then suggested a coup. I thought it was a great idea. I don't want to make excuses, but I can explain a bit. These things are easy with a blank sheet of paper, but our plan gradually morphed over time, thanks to months of frustration and difficulty. By the time we went ahead, we had a shit plan, no money and no time. That’s where we were when I was arrested in 2004.

Weren't the CIA involved somehow as well?

- I think the CIA originally suggested the coup to "The Boss", but then quit because they were worried it would go wrong. Everyone was talking about it, including British and Portuguese intelligence. It didn't look good for the Americans, because we’d bought a cheap Boeing 727 from their Air Force in Florida. Also, the guy I hired to ride shotgun in the plane is a known CIA pilot. I suspect it got to the point where Langley decided to torpedo our coup to remind Obiang they were in charge, and let them demand a change in Equatorial Guinea. From the day I was arrested, everything started to improve there.

But Human Rights Watch says it "remains mired in corruption, poverty, and repression".

- Yes, but people there will tell you that was the moment a lot of good stuff started to happen. It’s not a model of democracy, but they're making moves in the right direction. Two days before I was arrested, Riggs Bank – whose biggest customer was Obiang, as well as having a member of the Bush family on the board – closed down. It can only have been operating there with CIA approval.

How do you justify toppling governments for a job?

- Well, it’s not my job, but it’s what democracy is all about, in my opinion. In Angola, we were working for a proper, recognised government. In Sierra Leone, our actions led to an election. Equatorial Guinea was different because we were going against an existing government. Saddam, Gaddafi, Assad, all these guys are monsters and richly deserve to go. You have to be careful and it’s complicated, but bullies and tyrants are bad news. I really feel for the people of Syria, for example. Assad has turned the weight of a modern state against unarmed people. Fuck him.

White people running around Africa doing whatever they want – isn’t it all very colonial?

- Well, it at least it looks that way. But there are plenty of black mercenaries and plenty of white Africans running about as well. The danger is that, if people are making money out of wars, there's a risk they could start them. Aside from Equatorial Guinea, everything I’ve done involved terrible situations which were not of my making and which I was trying to end. That was our moral position. You have to look yourself in the mirror every morning, and pretty much everyone who’s ever seen a war knows they’re not nice. Full-on private militaries are bad news.

But that’s what you were doing.

- Yeah, but if you’re walking past a house and it’s on fire, you help to put it out. In my day, the UN was completely useless – they were spending billions and didn't put the fire out. We did. But intellectually, I don't think offensive fighting is for mercenaries. You need the mandate and the law of a government behind you. Once the motive is profit, things get impossibly difficult. Companies will cut corners to save cash, which isn't cool.

So those days are behind you?

- Well, no – I enjoy the work still. And if I saw a house on fire again, I’d say "OK," if I thought it was morally right.[34]

Mann in popular media

- In 2002 Mann played Colonel Derek Wilford of the Parachute Regiment for Granada Television's Bloody Sunday, a dramatisation by Paul Greengrass of the events of Bloody Sunday.[35]

- The alleged coup planned for Equatorial Guinea is the subject of the film Coup!, written by John Fortune. Simon Mann is played by Jared Harris, with Robert Bathurst as Mark Thatcher. (The film takes care not to suggest that Thatcher knew about the coup plot.) It was broadcast on BBC Two on 30 June 2006 and on ABC in Australia on 21 January 2008. [36]

- Simon Mann was interviewed from prison in the documentary Once Upon A Coup, which aired on PBS's Wide Angle in August 2009.

Memoirs

Mann's memoir, Cry Havoc, was published in 2011, to mixed reviews.[37][38]

See also

References

- ↑ "British coup plot mercenary Simon Mann has been pardoned"

- ↑ "Zimbabwe sends British mercenary to face the despot he plotted to overthrow"

- ↑ "SA court drops coup plot charges"

- ↑ "Coup plotter faces life in Africa's most notorious jail"

- ↑ "UK mercenary on trial in Equatorial Guinea"

- ↑ "Mann jailed for Eq. Guinea coup plot"

- ↑ "British mercenary Simon Mann receives presidential pardon"

- ↑ "Simon Mann returned to England", 6 November 2009

- ↑ "Secret MI6 plot to help Col Gaddafi escape Libya revealed"

- ↑ "Should Simon Mann be claiming a Wonga royalty?"

- ↑ "In It Together: The Inside Story of the Coalition Government"

- ↑ "The curious case of Simon Mann"

- ↑ "Perpetuating Disinformation" Eeben Barlow's Military and Security Blog

- ↑ "'Mercenary leader' found guilty"

- ↑ "Zimbabwe jails UK 'coup plotter'"

- ↑ "Mark Thatcher: Man on the run" In January 2005 Thatcher pled guilty in South Africa, after a plea bargain, to "unwittingly" abetting the coup. He was fined 3 million rand (£266,000), given a suspended four-year jail term, and obliged to leave South Africa, his home for a decade.

- ↑ "Coup plotters jailed in Equatorial Guinea"

- ↑ "Mann in the middle of two African dictators" Hugh Russell, The First Post, 2 May 2007.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS, Mann loses extradition appeal"

- ↑ "Zimbabwe deports Mann to Eq. Guinea"

- ↑ "Zimbabwe accused as Briton sent to Equatorial Guinea jail"

- ↑ "Business of the House"

- ↑ "Written answers -Foreign and Commonwealth affairs"

- ↑ "Foreign and Commonwealth affairs: Simon Mann"

- ↑ "Foreign and Commonwealth affairs – Equatorial Guinea"

- ↑ "Foreign and Commonwealth affairs: Simon Mann"

- ↑ "Foreign and Commonwealth affairs: Simon Mann"

- ↑ "Foreign and Commonwealth affairs: Simon Mann"

- ↑ "House of Lords – Equatorial Guinea: Simon Mann"

- ↑ "Foreign and Commonwealth affairs: Equatorial Guinea: Prisoners"

- ↑ "EDM: Conduct of Zimbabwe and Equatorial Guinea towards Simon Mann"

- ↑ "I was not the main man", Jonathan Miller, Channel 4, 11 March 2008.

- ↑ "Equatorial Guinea"

- ↑ "An interview with Simon Mann"

- ↑ "IMDb entry"

- ↑ "BBC Drama – Coup!"

- ↑ Tim Butcher, Daily Telegraph, 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Anthony Mockler, The Spectator, 26 November 2011.

Social media

On Twitter he is Simon Mann on Twitter.

His website is Captain Simon Mann.

External links

- Profile: Simon Mann, BBC News, 10 September 2004

- Simon Mann Dossier, by Journalismus Nachrichten von Heute

- Q&A: Equatorial Guinea coup plot, BBC World News

- "A Coup for a Mountain of Wonga"

- "British Mercenary Simon Mann's last Journey?"

- "The trial of Simon Mann"

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here