Document:The Balkan Wars

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Diana Johnstone on the Balkan Wars

Diana Johnstone’s book, Fools’ Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO and Western Delusions is essential reading for anybody who wants to understand the causes, effects, and rights-and-wrongs of the Balkan wars of the past dozen years. The book should be priority reading for leftists, many of whom have been carried along by a NATO-power party line and propaganda barrage, believing that this was one case where Western intervention was well-intentioned and had beneficial results. An inference from this misconception, by “cruise missile leftists” and others, is that imperialism can be constructive and its power projections must be evaluated on their merits, case by case. But that the Western intervention in the Balkans constitutes a valid special case is false; the conventional and obvious truths on the Balkan wars that sustain such a view disintegrate on close inspection.

Johnstone provides that close inspection, with impressive results. It is a pleasure to watch her dismantle the claims and expose the methods of David Rieff, a literary and media favorite, as well as Roy Gutman, John Burns, and David Rohde, three reporters whose close adherence to the party line in Bosnia was rewarded with the Pulitzer prize—all fueling the “humanitarian bombing” bandwagon. While critics of the party line risk being tagged and dismissed as apologists for the Serbs, even the most fervent partisan of an idealized “Bosnia” and campaigner for NATO military intervention such as Rieff, or the novice journalist Rohde, who wrote on Srebrenica in a semi-fictional mode, with U.S. intelligence guidance, has never had to fear being criticized as an apologist for the Muslims or NATO. Michael Ignatieff, another media favorite, acknowledges the help he has received from U.S. officials like Richard Holbrooke, General Wesley Clark and former Tribunal prosecutor Louise Arbour, and Rieff lauded him for his “close relations” with these “important figures in the West’s political and military leadership.” [1]

The widespread acceptance of the official connections, open advocacy, and spectacular bias displayed by these authors has rested in part on the usual media and intellectual community subservience to official policy positions, but it was also a result of the rapid and thoroughgoing demonization of the Serbs as the “new Nazis” or “last of the Communists.” Given that NATO was good, combatting evil, the close relationship with officials was not seen as involving any conflict of interest or compromise with objectivity; they were all on the same “team”—a phalanx seeking justice. Thus even the uncritical conduiting of anti-Serb propaganda—including unverified rumors and outright disinformation—was not only acceptable, it was capable of yielding journalistic honors.

On the other hand, any attempt to counter the official/media team’s claims and supposed evidence was quickly interpreted as apologetics. This is hardly new. In each U.S. war critics of U.S. policy are charged with being apologists for the demonized enemy—Ho Chi Minh and communism; Pol Pot; Saddam Hussein; Arafat; Daniel Ortega; Bin Laden, etc. The demonization of Milosevic was in accord with longstanding practice, and the charge of apologist for challenging the official line on the demon was inevitable for a forceful challenger. What is perhaps exceptional has been the extensive acceptance of the party line among people on the left, with, among others, Christopher Hitchens, [2] Ian Williams and the editors of The Nation in its grip. In These Times rejected first hand reporting from Kosovo by Johnstone, their longtime European Editor, when it diverged from the line of their more recent correspondent, Paul Hockenos, whose connections with the establishment included a stint as the spokesperson and media officer for the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe Mission to Bosnia-Herzegovina, acting as an occupying power in northern Bosnia-Herzegovina, and an affiliation with the American Academy in Berlin, whose chairman and co-chairman are Richard Holbrooke and Henry Kissinger. [3]

What makes the double standard in treatment of Johnstone and the “journalists of attachment” especially laughable is that Johnstone is a serious investigative journalist, very knowledgeable about Balkan history and politics, whose work in Fools’ Crusade sets a standard in cool examination of issues that is several grades higher than that in Rieff, Gutman, Rohde, Burns (and for that matter, Ignatieff, Timothy Garton Ash, Noel Malcolm, Hitchens, Williams, and Hockenos). On issue after issue she discusses both the evidence and counter-evidence, weighs them, gives them a historical and political context, and comes to an assessment, which is sometimes that the verifiable evidence doesn’t support a clear conclusion. She does this convincingly, and in the process lays waste to the established version.

For example, Johnstone notes that in late September, 1991, some 120 Serbs in the Croatian town of Gospic were abducted and massacred in what Croatian human rights activists called the first major massacre of civilians in the Yugoslav civil wars. Although this was clearly designed to frighten the Serbs into moving, the term “ethnic cleansing” was only taken up by the Western media months later in reference to Serb treatment of Muslims in Bosnia. The Gospic slaughter was barely noticed, and only hit the news in 1997 when a disgruntled former policeman, Miro Bajramovic went public, claiming that the Gospic massacre was done on orders from the Croatian Interior Ministry to spread terror among the Serbs. Bajramovic was quickly imprisoned in Croatia and tortured, and no moves were taken to deal with the crimes he named either within Croatia or by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (hereafter, ICTY, or Tribunal).

Shortly thereafter three other Croatian soldiers risked their lives to take videotapes and documents on this massacre to the Hague, but the Tribunal refused to offer them protection; one was murdered, the others fled Gospic, and while Tribunal prosecutor Carla Del Ponte insisted that the Tribunal must have priority over Serb courts in dealing with Serbs, she waived priority in dealing with Croats. Thus, nothing was done regarding Gospic except the harassment, torture and killing of witnesses. [4]

One of the Croatian officers leading the attacks on Serbs, an Albanian, Agim Ceku, was subsequently trained by “retired” U.S. army officers on contract to Croatia, and he helped command “Operation Storm” in 1995, in which hundreds of Serb civilians were killed and Krajina was ethnically cleansed of several hundred thousand Serbs in what was probably the largest single ethnic cleansing operation in the Balkan wars. Ceku later returned to Kosovo to join the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and worked with them during the 1999 bombing war. Ceku has not only never been indicted by the Tribunal, in January 2000 he was sworn in by NATO’s proconsul in Kosovo, Bernard Kouchner, as chief of the “Kosovo Protection Corps,” the new look KLA.

You may not have heard of Gospic or Ceku, and Nasir Oric is also not a name featured by Rieff, the media, or the Tribunal. Arkan is a more familiar name. Arkan was a Serb paramilitary leader, eventually indicted by the Tribunal, just as NATO started to bomb Yugoslavia in March 1999, no doubt coincidentally providing exemplary public relations service to NATO. Nasir Oric was a Bosnian Muslim officer operating out of Srebrenica, from which “safe haven” Oric ventured out to attack nearby Serb villages, burning homes and killing over a thousand Serbs between May 1992 and January 1994. Oric even invited Western reporters to his apartment to see his “war trophies”: videocassettes showing cut- off Serb heads, burnt houses, and piles of corpses. [5]

You thought that Srebrenica was a “safe haven” only for civilians and that it could hardly be a UN cover for Bosnian Muslim military operations? You were misinformed. [6] You hadn’t heard of the 1992 pushing out of Serbs from Srebrenica and the multiyear attacks on nearby Serb towns and massacres that preceded the Srebrenica massacre (discussed further below)? In fact, it has been an absolute rule of Rieff et al./media reporting on the Bosnian conflict to present evidence of Serb violence in vacuo, suppressing evidence of prior violence against Serbs, thereby falsely suggesting that Serbs were never responding but only initiated violence (this applies to Vukovar, Mostar, Tuzla, Gorazde, and many other towns). [7]

You hadn’t heard of Nasir Oric and can’t understand why he has never been indicted by the Tribunal although doing the same sort of thing as Arkan, but perhaps on a somewhat larger scale? It is not puzzling at all if you realize that the “phalanx” I mentioned above which includes Rieff et al., the media, and the Tribunal, also includes the NATO powers and is serving their ends, which did not include justice (see below).

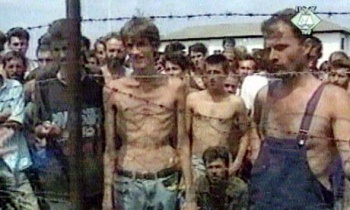

Johnstone provides many examples of how the phalanx twisted facts for political ends, including an extensive and compelling analysis of the various non-proofs of “systematic rape” as Serb policy. [8] But the choicest morsel showing how the propaganda system works was the Nazi-style “death camp” with its picture of the “thin man” Fikret Alic behind barbed wire. As Johnstone notes, the Bosnian Muslims and Croatians also had prison camps during the Bosnian wars, but Radovan Karadzic, the “indicted war criminal,” was not as smart as they were—he allowed the Western media to visit his camps.

It is now well established as truth, if not permitted to surface in the mainstream media, that:

- the thin man was not behind barbed wire — the barbed wire was around a small unused compound from which the photographers from Britain’s Independent Television Network took their pictures;

- he was not even in a prison camp, let alone a death camp, but was in transit through a refugee center, on his way to exile in Scandinavia;

- the thinness of Fikret Alic was not typical of people in the camp, but was highlighted to fit the “Auschwitz” image.

Nevertheless, “in August 1992, the ‘thin man behind barbed wire’ photos made the tour of the front pages of virtually every tabloid newspaper in the Western world and appeared on the cover of Time, Newsweek, and other mass circulation magazines.” [9] The U.S. proposal for a war crimes tribunal followed in the same month, and German Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel, featuring the evidence of the “thin man” photo, made it clear that the Tribunal’s function was to prosecute Serbs, who were ethnic cleansing “to achieve their national goals in Bosnia-Herzegovina [which] is genocide.” This was only one of many frauds based on disinformation, but it was a major one, helping make the Serbs-as-Nazis a given for the phalanx and much of the Western public. [Wikispooks note: The picture was still being used by Western 'Progressive/Left' media as late as 2008 when the ICTYas this report by Ed Vulliamy in the UK Guardian illustrates]

"Milosevic Started It All"

Central to the party line of NATO and the phalanx has been the theme that Milosevic is the demon who started it all by his nationalist quest for a “Greater Serbia” and his (and Serbia’s) view that non-Serbs “had no place in their country, and even no right to live” (Clinton). According to David Rieff, Milosevic “had quite correctly been described by U.S. officials …as the architect of the catastrophe,” [10] and Tim Judah referred to Milosevic’s responsibility for wars in “Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo: four wars since 1991 and the result of these terrible conflicts, which began with the slogan ‘All Serbs in One State’ is the cruelest of ironies.” [11]

On its face this perspective seems simple-minded, and is even referred to by a more sophisticated analyst than Rieff or Judah, Lenard Cohen, a bit sardonically, as the “paradise lost/loathsome leaders perspective” on history. [12] Johnstone’s book destroys this party line by a convincing analysis of the dynamics of the conflict observable in the actions and interests of all the parties involved, extending even to expatriate lobbying groups of the Croatians and Albanians.

In her enlightening chapter on Germany, Johnstone describes its hostility to Serbia and contacts with Croatian emigre groups long before the arrival of Milosevic. Germany had attacked Serbia during World War I and then again under the Nazis; whereas the Croatians and Kosovo Albanians had been German allies. Germany under the Nazis had regularly used the gambit of siding with “ethnic minorities” as a means of weakening rival or target states, and with the death of the Soviet Union and the end of Western support of a unified and independent Yugoslavia, and German reunification, Germany renewed that gambit as it aimed to consolidate its power in Eastern Europe. Germany encouraged the unilateral secession of Slovenia and Croatia and pressured her Maastricht allies to go along with supporting this secession, although it was unnegotiated and in violation of international law.

At the same time as the Europeans encouraged the secession of Slovenia and Croatia, and the United States threatened Yugoslavia if it tried to maintain its borders by use of its army, the NATO alliance failed to deal with the threat to the stranded minorities in the seceding territories. The EU-appointed Badinter commission even announced in November 1991 that Yugoslavia was “in a process of dissolution,” which helped accelerate the dissolution; and by giving recognition to the artificial boundaries of the “Republics,” while refusing to consider the demands of the large groups within those Republics that wanted to stay in Yugoslavia, Badinter provided an ideal formula for producing ethnic warfare. This was not Milosevic causing trouble, it was the Germans and other NATO powers who encouraged dissolution without offering any constructive solution to minority demands (Johnstone discusses some of the ignored possibilities).

Their obvious bias against the Serbs, and encouragement to the national groups opposed to the Serbs, also maximized the threat to peace, as it made the Serbs justly suspicious of NATO intentions and encouraged the other groups to resist a negotiated settlement and provoke the Serbs into actions that would increase NATO intervention on their behalf. This was dramatically evident in Bosnia, where the European powers arranged for an independence vote in 1992, despite the fact that the Bosnia-Herzegovina constitution required that such a vote be taken only upon agreement among the republic’s three “constituent peoples” (Muslims, Croats and Serbs). The Bosnian Serbs boycotted this election, and the creation of this artificial and badly divided state assured war and ethnic cleansing. This again was a catastrophic decision made by the NATO powers, not by Milosevic.

Johnstone has an extensive discussion of the brutal historical background of Bosnia- Herzegovina (and Croatia), which had been the scene of massive inter-group crimes during World War II. [13] She also demonstrates clearly that Bosnia was no multiethnic paradise upset by Serb violence, in the myth perpetrated by Rieff et al. and the NATO media. Johnstone points out that even as early as December 1990, in elections in Bosnia the nationalist parties won easily, capturing 90 percent of the votes, suggesting something other than a non-nationalistic society. She also provides solid evidence that Alija Izetbegovic, the Muslim leader of Bosnia in the war years, was a committed believer in an Islamic—not a multiethnic—state, and a man who regarded Turkey as too advanced and modernist, preferring Pakistan as his Islamic model. The thousands of Mujahidden fighters, including Al Qaeda militants, that he welcomed to fight for his cause, and the massive aid given him by Saudi Arabia, were not supplied in the cause of multi-ethnicity.

Johnstone shows that with U.S. aid and encouragement Izetbegovic fought any settlement that would result in autonomy for the major national groups. He, like the KLA, realized that he could pursue a maximalist strategy by getting the more-than-willing United States to support him both diplomatically and, increasingly, by military means. Milosevic, and to a lesser extent the Bosnian Serbs, were repeatedly willing to sign compromise agreements, but Izetbegovic repeatedly refused, with U.S. support—most importantly, in the case of the “Lisbon Accord” of March 1992, which was signed by all three parties, but from which Izetbegovic withdrew, on U.S. advice. Milosevic also supported the Owen-Vance plan of 1992, vetoed by the Bosnian Serbs, to Milosevic’s disgust. This diplomatic history is well documented in Lord David Owen’s memoir, Balkan Odyssey, which is why this Britisher’s work is not well regarded by the party liners. Richard Holbrooke acknowledges Milosevic’s efforts to save the Dayton accord from Izetbegovic’s foot-dragging, and the 1995 U.S. bombing of Bosnian Serbs may have been part of the price paid to get Izetbegovic, not Milosevic, to negotiate at Dayton. [14]

Johnstone’s detailed account of Croatia stresses the genocidal behavior of the Croats toward the Serbs in World War II; the long- standing backing of the nationalist movement in Croatia by Germany, Austria, and the Vatican; the importance of the Croatian lobby in the United States and elsewhere in mobilizing support for their breakaway from Yugoslavia; and Croatia’s skilled propaganda efforts, helped along by their employment of public relations firm Ruder Finn. “News” about Croatia and its victimization by Serbia flowed from Zagreb and Ruder Finn. Quite independently of Milosevic the Croatian nationalists, led by Franjo Tudjman from 1990, were clearly aiming at a “Greater Croatia” that would include a part of Bosnia, as well as the Serb- inhabited Krajina area. As convincingly described by Johnstone, it was a masterpiece of effective propaganda that Croatia’s war in Bosnia and expulsion of a quarter million Serbs from Krajina (with active U.S. assistance) was portrayed in the West not as part of a quest for a Greater Croatia, but as a resistance to Milosevic’s striving for a Greater Serbia.

According to Clinton and mainstream commentary, Milosevic’s drive for a Greater Serbia and nationalism was demonstrated by his inflammatory nationalistic speeches of 1987 and 1989. This is a perfect illustration of the profound role of disinformation in the demonization process. The two famous speeches DENOUNCE nationalism: Milosevic actually said that “Yugoslavia is a multinational community, and it can survive only on condition of full equality of all nations that live in it.” Nothing in the two speeches contradicts this sentiment.

In dispelling the “myth” of Milosevic, Johnstone hardly puts him on a pedestal. He was an opportunistic politician, “whose ‘ambiguity’ allowed him to win elections, but not to unite the Serbs.” Milosevic gained popularity by condemning both Serbian nationalism and Communist bureaucracy, and by promising economic reforms in line with the demands of the Western financial community. In Johnstone’s view, Milosevic can be regarded as a criminal “if using criminals to do dirty tasks makes him a criminal,” but on this count he was “no more [guilty] (or rather less) than the late President Tudjman of Croatia or President Alija Izetbegovic of Bosnia, widely regarded as a saint.” He was less a nationalist than Tudjman and Izetbegovic, and claims that he had “dehumanizing beliefs” and an “eliminationist project” are taken out of the whole cloth. [15]

Milosevic’s alleged pursuit of a Greater Serbia was also a misreading of his actual policies, which were, first, to prevent the disintegration of Yugoslavia, and second, as that disintegration occurred to protect the Serb minorities in the new states and allow them either to remain in Yugoslavia or obtain autonomy in the new rump states. In fact, he was considered by the Bosnian Serbs and Krajina victims of Operation Storm to be a sell- out, eager to bargain away their interests in exchange for a possible lifting of sanctions on Yugoslavia. He did support the Bosnian Serbs, sporadically, but it is rarely mentioned that all the NATO powers and Saudia Arabia and Al Qaeda were supporting the Bosnian Muslims (and Croatia was supporting its allies in Bosnia).

So Milosevic was guilty of pursuing a Greater Serbia by trying to prevent the dissolution of Yugoslavia and feebly seeking to give stranded and threatened Serb populations protection! His “war” against Slovenia—one of those “terrible conflicts” Tim Judah attributes to Milosevic—was a half-hearted ten-day effort to prevent an illegal secession of that Republic, quickly terminated with minimal (and mainly Yugoslav army) casualties. Meanwhile, Tudjman, quite openly seeking a Greater Croatia, and Izetbegovic, trying to leverage U.S. and other NATO hostility to Yugoslavia into a means of compelling unwanted Greater Muslim rule in Bosnia, were just victims of the bad man! This is Orwell written into mainstream truth.

The same is true of the Kosovo struggle. There is no question but that Milosevic’s crackdown in 1989 was brutal, and that police and army actions against the KLA in later years were sometimes ruthless, but the phalanx has ignored a number of key facts. One is that Kosovo was largely run by Albanians before 1989, and the first target of the 1989 crackdown was the old bureaucracy run by Albanian communists. Second, under their rule it was Serbs who were discriminated against and driven out of Kosovo. In the 1980s and earlier Kosovo Albanian nationalists were openly engaging in “ethnic cleansing” in the interests of a homogenous Albanian state, and in the 1990s the movement became strictly irredendist, aiming not at reform but exit from Yugoslavia. The movement’s leaders were also more openly interested in a “Greater Albania.” As in the case of the Izetbegovic faction of the Bosnian Muslims, the KLA soon saw that by provocation and effective propaganda it would be possible to get NATO to serve as its military arm.

Johnstone describes the Yugoslav efforts to compromise and give the Albanians greater autonomy, and she notes the complete failure of the NATO powers to seek any kind of mediated solution (including a division of the Kosovo territory). The war engineered by the KLA and United States then ensued, with disastrous results. In Kosovo it produced great destruction, an immense flight of refugees, with thousands of casualties and a fresh injection of hatred on all sides that contradicted the alleged NATO aim of producing a genuine multiethnic community. This was followed by a massive ethnic cleansing of Serbs, Roma, Turks and Jews by the NATO-supported KLA, and Kosovo was left “without a legal system, ruled by illegal structures of the Kosovo Liberation Army and very often by competing mafias” (quoting Jiri Dienstbier, UN human rights rapporteur in Kosovo). Under NATO auspices, and helped along by leaders of Albania, a new advance was made in the aim of a “Greater Albania” in Macedonia and possibly elsewhere. Finally, Serbia was very badly damaged by the war, reduced to penury and dependency, conflict ridden and with a sham democracy in place.

Of course, there was Srebrenica. But since so much in this establishment Balkan story consists of lies and half-truths, is it possible that the establishment version of this story is also misleading? Johnstone examines the various sources and finds considerable uncertainty regarding two issues: the number of victims, and the motives of the combatants. [16] It is true that 199 bodies were found bound or blindfolded following the Bosnian Serb occupation of the town in July 1995, almost surely slaughtered by the Bosnian Serb attackers. But what about the alleged 8,000 killed? The figure of 8,000 seems to have been arrived at by adding a Red Cross estimate of 3,000 that “witnesses” said were detained by the Bosnian Serbs to the figure of 5,000 who the Red Cross said “fled Srebrenica, some of whom reached Central Bosnia.” Although there was no reason from this accounting to add the 5,000 as killed, this became conventional truth. The Bosnian Muslims shrewdly refused to tell the Red Cross how many had survived, helping suggest that they were all dead.

Six years later, Tribunal forensic teams had uncovered 2,361 bodies in this region of heavy fighting, many almost surely fallen soldiers on both sides. Recall also that the United States had engaged in intensive satellite imaging of this area, and Madeleine Albright had even promised to keep watching to see if the Bosnian Serbs disturbed the graves. But she never produced for public view any satellite photo showing bodies being deposited in or removed from graves.

As to motive for the killings that took place, it is interesting that the significant killings (and expulsions) of Serbs (and Roma) in (and from) Kosovo after the NATO takeover were regularly treated in the West as “revenge,” whereas the killings in and around Srebrenica, plausibly attributable to Bosnian Serb anger at the prior murderous operations of Nasir Oric against Serbs in the Srebrenica vicinity, were not “revenge” but “genocide” in the Western system of double standards. As noted, this rests in good part on the blackout of the prior events associated with Nasir Oric and his Bosnian Muslim forces.

Johnstone has a devastating account of the work of the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia, showing its political origin, purpose and service, as well as its violation of all Western judicial norms (including its use of “indictments” to condemn and ostracize without trial). Among many other points featured is the fact that the Tribunal has only sought to establish responsibility at the top for Serbs, never for Croatian or Bosnian Muslim leaders. Johnstone also notes the unwillingness to indict any NATO personnel or officials for readily documented war crimes. She also points out that the indictment of Milosevic on May 27, 1999, based on unverified information provided by U.S. intelligence one day earlier, was needed by NATO to cover over its intensifying bombing of Serbian civilian sites, in straightforward violation of international law. As Clinton said, “The indictment confirms that our war is just,” but it much more clearly confirmed that the Tribunal was a political, not a judicial institution.

A further illustration is afforded in her enlightening account of the novel “hearing” on the Karadzic case in July 1996, where the Tribunal innovated a judicial rule whereby Karadzic’s attorney was not allowed to offer a defense of his client; he could merely observe. The main evidence of Karadzic’s “genocidal intent” was a phrase he uttered in 1991 while calling on Izetbegovic to recognize the Bosnian Serbs desire to remain in Yugoslavia, saying that “do not think that you will not perhaps make the Muslim people disappear, because the Muslims cannot defend themselves if there is a war—How will you prevent everyone from being killed in Bosnia- Herzegovina?” Although this muddled sentence issued in the heat of debate could be interpreted as a warning of the dangers of war, and comparable statements were made by Izetbegovic and many others, this was presented by the Tribunal as serious evidence of genocidal intent.

Johnstone contends that the United States was a participant in the Balkan wars for a number of reasons, including the desire to maintain its role as leader of NATO and to help provide it with a function on its 50th anniversary year (celebrated in the midst of the 78-day bombing war in April 1999); if Germany and others were going to intervene in Yugoslavia, the United States would have to enter and play its role, and incidentally show that in the use of force it was still champion. The United States was also helping itself in its Bosnian intervention by demonstrating its willingness to aid Muslims, contradicting its image as anti-Muslim, and solidifying its relationship with Turkey and other Muslim countries helping in the Bosnian war. It was also positioning itself for further advances in the region with a major military base in Kosovo and new clients in an area of increasing interest with links to the Caspian basin. The humanitarian motive was contradicted by inherent implausibility and by the nature and inhumanitarian results of the U.S. and NATO intervention.

All-in-all the United States did well from its intervention, but the people of the area did poorly. The policies of it and its European allies were primary causes of the breakup of Yugoslavia and the failure to manage any split peaceably. Their intervention was not “too late,” but early, destructive, and well designed to encourage the ethnic cleansing that followed. Subsequently, they failed to mediate the conflict in Kosovo and collaborated with the KLA in producing a highly destructive war, followed by an occupation in which REAL ethnic cleansing took place, with NATO acquiesence and even cooperation. Bosnia and Kosovo are under colonial occupation. The remnant Yugoslavia, once a vibrant and truly multiethnic state, is poor, crowded with refugees, dependent on a hostile West, conflict-ridden, and rudderless. The Balkans are neither stable nor free; their future as NATO clients does not look promising.

Diana Johnstone has written up this story in a readable, scholarly, and convincing way that I have been able to summarize all to briefly here. It is an important book, especially for a left that has been confused by the outpourings of a very powerful propaganda system.

Notes

- ^ . David Rieff, “Virtual War: Kovoso and Beyond,” Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2000; Michael Ignatieff, Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2000), p. 6.

- ^ . Christopher Hitchens is properly referred to as an ex-leftist, who is now a reliable apologist for imperial wars. However, his furiously anti-Serb and pro-Bosnian Muslim and pro-NATO war biases date back to the early 1990s when he joined the “Potemkin Sarejevo” groupies in a new cult idealizing and misreading the facts on Izetbegovic and the allegedly multiethnic paradise now being upset by the Serbs. For an excellent account, Johnstone, Fools’ Crusade, pp. 40-64.

- ^ . See my Open Letter Reply to Paul Hockenos and In These Times on Their Coverage of the Balkans: http://www.zmag.org/openhermanitt.htm

- ^ . Johnstone, pp. 27-32.

- ^ . John Pomfret reported on Nasi Oric’s trophies in a unique article on “Weapons, Cash and Chaos Lend Clout to Srebrenica’s Tough Guy,” Washington Post, February 16, 1994.

- ^ . Johnstone, p. 110.

- ^ . Among the sources on this point, providing documentation that included numerous personal affidavits, all ignored by Rieff et al. and the Western media: S. Dabic et al., “Persecution of Serbs And Ethnic Cleansing in Croatia 1991-1998, Documents and Testimonies,” Serbian Council Information Center, Belgrade, 1998; “Memoradum on War Crimes and Crimes and Genocide in Eastern Bosnia (Communes of Bratunac, Skelani and Srebrenica) Committed Against the Serbian Population From April 1992 to April 1993,” sent by Ambassador Dragomir Djokic to the General Assembly and Security Council, June 2, 1993; Milovoje Ivanisevic, “Expulsion of the Serbs From Bosnia and Herzogovina, 1992-1995,” Edition WARS, Book II, Belgrade, 2000. See also Steven L. Burg and Paul S. Shoup, The War in Bosnia- Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention ( Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1999), pp. 178-180; Raymond K. Kent, “Contextualizing Hate: The Hague Tribunal, the Clinton Administration and the Serbs”: http://www.beograd.com/nato/texts/english/c/contextualizing_hate. html

- ^ . Johnstone, pp. 78-90

- ^ . Ibid., p. 73.

- ^ . David Rieff, “A New Age of Liberal Imperialism,” World Policy Journal, Summer 1999.

- ^ . Tim Judah, “Is Milosevic Planning Another Balkan War?,” Scotland on Sunday, March 19, 2000.

- ^ . Lenard Cohen, Serpent in the Bosom: The Rise and Fall ofSlobodan Milosevic (Boulder. Col.: Westview Press, 2001), p. 380.

- ^ . Johnstone, pp. 23-32, 144-156.

- ^ . Ibid., pp. 60-61

- ^ . Ibid., pp. 16-23.

- ^ . Ibid., pp. 109-118.