Difference between revisions of "Peter Kropotkin"

(Added: wikiquote, spouses.) |

(unstub) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Kropotkin | |wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Kropotkin | ||

|spartacus=http://spartacus-educational.com/USAkropotkin.htm | |spartacus=http://spartacus-educational.com/USAkropotkin.htm | ||

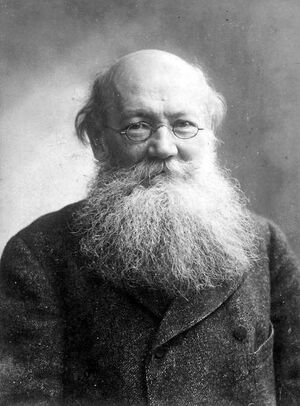

| − | |image= | + | |image=Peter Kropotkin circa 1900.jpg |

| − | |birth_date=1842 | + | |birth_date=9 December 1842 |

| − | |death_date=1921 | + | |death_date=8 February 1921 |

| + | |interests=anarchism | ||

| + | |description=Anarchist philosopher promoting a decentralized economic system based on mutual aid, mutual support, and voluntary cooperation | ||

|constitutes=activist, scientist, philosopher | |constitutes=activist, scientist, philosopher | ||

|alma_mater=Saint Petersburg Imperial University | |alma_mater=Saint Petersburg Imperial University | ||

| Line 14: | Line 16: | ||

|employment= | |employment= | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin''' was a Russian [[anarchist]], [[socialist]], [[revolutionary]], [[historian]], [[scientist]],<ref>Stoddart, D. R. (1975). "Kropotkin, Reclus, and 'Relevant' Geography". Area. 7 (3): 188–190. </ref> [[philosopher]], and [[activist]] who advocated [[anarcho-communism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Born into an [[aristocratic]] land-owning family, Kropotkin attended a military school and later served as an officer in [[Siberia]], where he participated in several geological expeditions. He was imprisoned for his activism in 1874 and managed to escape two years later. He spent the next 41 years in exile in [[Switzerland]], [[France]] (where he was imprisoned for almost four years) and [[England]]. While in exile, he gave lectures and published widely on anarchism and geography.<ref>{Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 414. </ref> Kropotkin returned to Russia after the [[Russian Revolution]] in 1917, but he was disappointed by the [[Bolshevik]] state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kropotkin was a proponent of a [[Libertarian socialist decentralisation|decentralised]] [[communist society]] free from central government and based on voluntary associations of self-governing communities and worker-run enterprises. He wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being ''[[The Conquest of Bread]]'' and ''[[Fields, Factories and Workshops]]'', but also ''[[Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution]]'', his principal scientific offering. He contributed the article on anarchism to the ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition]]''<ref>https://archive.org/details/PeterKropotkinEntryOnanarchismFromTheEncyclopdiaBritannica</ref> and left unfinished a work on anarchist ethical philosophy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Philosophy== | ||

| + | === Critique of capitalism === | ||

| + | Kropotkin pointed out what he considered to be the fallacies of the [[Economics#Criticisms|economic systems]] of [[feudalism]] and [[Criticism of capitalism|capitalism]]. He believed they create poverty and [[artificial scarcity]], and promote [[Privilege (social inequality)|privilege]]. Instead, he proposed a more decentralized economic system based on mutual aid, [[mutual aid (organization)|mutual support]], and [[cooperation|voluntary cooperation]]. He argued that the tendencies for this kind of organization already exist, both in evolution and in human society.<ref>https://archive.org/details/mutualaidafacto00knigoog</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kropotkin disagreed in part with the Marxist critique of capitalism, including the [[labour theory of value]], believing there was no necessary link between work performed and the values of commodities. His attack on the institution of wage labour was based more on the power employers exerted over employees, and not only on the extraction of [[surplus value]] from their labour. Kropotkin claimed this power was made possible by the state's protection of private ownership of productive resources.<ref>https://books.google.com/books?id=3PoqAJrrYtAC&q=kropotkin+labor+theory&pg=PT18</ref> However, Kropotkin believed the possibility of surplus value was itself the problem, holding that a society would still be unjust if the workers of a particular industry kept their surplus to themselves, rather than redistributing it for the common good.<ref>Kropotkin, Peter (2011). ''The Conquest of Bread.'' Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 50, 101–102.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Cooperation and competition === | ||

| + | In 1902, Kropotkin published his book ''[[Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution]]'', which gave an alternative view of animal and human survival. At the time, some "[[social Darwinism|social Darwinists]]" such as [[Francis Galton]] proffered a theory of interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy. Instead, Kropotkin argued that "it was an evolutionary emphasis on cooperation instead of competition in the Darwinian sense that made for the success of species, including the human".<ref name=Sale>https://web.archive.org/web/20101212113034/http://amconmag.com/article/2010/jul/01/00045/</ref> In the last chapter, he wrote: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{QB|In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense – not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species […] in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits […] and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development […] are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.<ref>http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Kropotkin#Mutual_Aid:_A_Factor_of_Evolution_.281902.29 </ref>}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kropotkin did not deny the presence of competitive urges in humans, but did not consider them the driving force of history.<ref name=Gallaher>https://books.google.com/books?id=XpBJclVnVdQC&pg=PA262</ref> He believed that seeking out conflict proved to be socially beneficial only in attempts to destroy unjust, authoritarian institutions such as the State or [[organized religion|the Church]], which he saw as stifling human creativity and impeding human instinctual drive towards cooperation.<ref>https://books.google.com/books?id=dh1NvIxiaIIC&pg=PA349</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kropotkin's observations of cooperative tendencies in [[indigenous people]]s (pre-feudal, feudal, and those remaining in modern societies) led him to conclude that not all human societies were based on competition as were those of industrialized Europe, and that many societies exhibited cooperation among individuals and groups as the norm. He also concluded that most pre-industrial and pre-authoritarian societies (where he claimed that [[leadership]], central government, and class did not exist) actively defend against the accumulation of private property by equally distributing within the community a person's possessions when they died, or by not allowing a gift to be sold, bartered or used to create wealth, in the form of a [[gift economy]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Mutual aid === | ||

| + | In his 1892 book ''[[The Conquest of Bread]]'', Kropotkin proposed a system of economics based on mutual exchanges made in a system of voluntary cooperation. He believed that in a society that is socially, culturally, and industrially developed enough to produce all the goods and services it needs, there would be no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or monetary exchange, to prevent everyone to take what they need from the social product. He supported the eventual abolition of money or tokens of exchange for goods and services.<ref>https://archive.org/details/conquestbread00kropgoog</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kropotkin believed that [[Mikhail Bakunin]]'s [[Collectivist anarchism|collectivist]] economic model was just a wage system by a different name<ref>Kropotkin wrote: "After the Collectivist Revolution instead of saying 'twopence' worth of soap, we shall say 'five minutes' worth of soap." (quoted in (quoted in Brauer, Fae (2009). ''"Wild Beasts and Tame Primates: 'Le Douanier' Rosseau's Dream of Darwin's Evolution".'' In Larsen, Barbara Jean (ed.). The Art of Evolution: Darwin, Darwinisms, and Visual Culture. UPNE. p. 211.</ref> and that such a system would breed the same type of centralization and inequality as a capitalist wage system. He stated that it is impossible to determine the value of an individual's contributions to the products of social [[Wage labour|labour]], and thought that anyone who was placed in a position of trying to make such determinations would wield authority over those whose wages they determined.<ref>Avrich, Paul (2005). ''The Russian Anarchists.'' AK Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781904859482.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to [[Kirkpatrick Sale]], "[w]ith ''Mutual Aid'' especially, and later with ''[[Fields, Factories, and Workshops]]'', Kropotkin was able to move away from the absurdist limitations of [[individual anarchism]] and no-laws anarchism that had flourished during this period and provide instead a vision of [[communal anarchism]], following the models of independent cooperative communities he discovered while developing his theory of mutual aid. It was an anarchism that opposed centralized government and state-level laws as traditional anarchism did, but understood that at a certain small scale, communities and communes and co-ops could flourish and provide humans with a rich material life and wide areas of liberty without centralized control."<ref name=Sale/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{{SMWDocs}} | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | {{ | + | |

| + | {{PageCredit | ||

| + | |site=Wikipedia | ||

| + | |date=08.08.2022 | ||

| + | |url=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Kropotkin | ||

| + | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:45, 13 August 2022

(activist, scientist, philosopher) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin 9 December 1842 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 8 February 1921 (Age 78) Dmitrov, Russian SFSR |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg Imperial University |

| Spouse | Sofia Ananiev |

| Interests | anarchism |

Anarchist philosopher promoting a decentralized economic system based on mutual aid, mutual support, and voluntary cooperation | |

Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist,[1] philosopher, and activist who advocated anarcho-communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended a military school and later served as an officer in Siberia, where he participated in several geological expeditions. He was imprisoned for his activism in 1874 and managed to escape two years later. He spent the next 41 years in exile in Switzerland, France (where he was imprisoned for almost four years) and England. While in exile, he gave lectures and published widely on anarchism and geography.[2] Kropotkin returned to Russia after the Russian Revolution in 1917, but he was disappointed by the Bolshevik state.

Kropotkin was a proponent of a decentralised communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations of self-governing communities and worker-run enterprises. He wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops, but also Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, his principal scientific offering. He contributed the article on anarchism to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition[3] and left unfinished a work on anarchist ethical philosophy.

Contents

Philosophy

Critique of capitalism

Kropotkin pointed out what he considered to be the fallacies of the economic systems of feudalism and capitalism. He believed they create poverty and artificial scarcity, and promote privilege. Instead, he proposed a more decentralized economic system based on mutual aid, mutual support, and voluntary cooperation. He argued that the tendencies for this kind of organization already exist, both in evolution and in human society.[4]

Kropotkin disagreed in part with the Marxist critique of capitalism, including the labour theory of value, believing there was no necessary link between work performed and the values of commodities. His attack on the institution of wage labour was based more on the power employers exerted over employees, and not only on the extraction of surplus value from their labour. Kropotkin claimed this power was made possible by the state's protection of private ownership of productive resources.[5] However, Kropotkin believed the possibility of surplus value was itself the problem, holding that a society would still be unjust if the workers of a particular industry kept their surplus to themselves, rather than redistributing it for the common good.[6]

Cooperation and competition

In 1902, Kropotkin published his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which gave an alternative view of animal and human survival. At the time, some "social Darwinists" such as Francis Galton proffered a theory of interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy. Instead, Kropotkin argued that "it was an evolutionary emphasis on cooperation instead of competition in the Darwinian sense that made for the success of species, including the human".[7] In the last chapter, he wrote:

In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense – not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species […] in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits […] and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development […] are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.[8]

Kropotkin did not deny the presence of competitive urges in humans, but did not consider them the driving force of history.[9] He believed that seeking out conflict proved to be socially beneficial only in attempts to destroy unjust, authoritarian institutions such as the State or the Church, which he saw as stifling human creativity and impeding human instinctual drive towards cooperation.[10]

Kropotkin's observations of cooperative tendencies in indigenous peoples (pre-feudal, feudal, and those remaining in modern societies) led him to conclude that not all human societies were based on competition as were those of industrialized Europe, and that many societies exhibited cooperation among individuals and groups as the norm. He also concluded that most pre-industrial and pre-authoritarian societies (where he claimed that leadership, central government, and class did not exist) actively defend against the accumulation of private property by equally distributing within the community a person's possessions when they died, or by not allowing a gift to be sold, bartered or used to create wealth, in the form of a gift economy.

Mutual aid

In his 1892 book The Conquest of Bread, Kropotkin proposed a system of economics based on mutual exchanges made in a system of voluntary cooperation. He believed that in a society that is socially, culturally, and industrially developed enough to produce all the goods and services it needs, there would be no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or monetary exchange, to prevent everyone to take what they need from the social product. He supported the eventual abolition of money or tokens of exchange for goods and services.[11]

Kropotkin believed that Mikhail Bakunin's collectivist economic model was just a wage system by a different name[12] and that such a system would breed the same type of centralization and inequality as a capitalist wage system. He stated that it is impossible to determine the value of an individual's contributions to the products of social labour, and thought that anyone who was placed in a position of trying to make such determinations would wield authority over those whose wages they determined.[13]

According to Kirkpatrick Sale, "[w]ith Mutual Aid especially, and later with Fields, Factories, and Workshops, Kropotkin was able to move away from the absurdist limitations of individual anarchism and no-laws anarchism that had flourished during this period and provide instead a vision of communal anarchism, following the models of independent cooperative communities he discovered while developing his theory of mutual aid. It was an anarchism that opposed centralized government and state-level laws as traditional anarchism did, but understood that at a certain small scale, communities and communes and co-ops could flourish and provide humans with a rich material life and wide areas of liberty without centralized control."[7]

References

- ↑ Stoddart, D. R. (1975). "Kropotkin, Reclus, and 'Relevant' Geography". Area. 7 (3): 188–190.

- ↑ {Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 414.

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/PeterKropotkinEntryOnanarchismFromTheEncyclopdiaBritannica

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/mutualaidafacto00knigoog

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=3PoqAJrrYtAC&q=kropotkin+labor+theory&pg=PT18

- ↑ Kropotkin, Peter (2011). The Conquest of Bread. Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 50, 101–102.

- ↑ Jump up to: a b https://web.archive.org/web/20101212113034/http://amconmag.com/article/2010/jul/01/00045/

- ↑ http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Kropotkin#Mutual_Aid:_A_Factor_of_Evolution_.281902.29

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=XpBJclVnVdQC&pg=PA262

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=dh1NvIxiaIIC&pg=PA349

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/conquestbread00kropgoog

- ↑ Kropotkin wrote: "After the Collectivist Revolution instead of saying 'twopence' worth of soap, we shall say 'five minutes' worth of soap." (quoted in (quoted in Brauer, Fae (2009). "Wild Beasts and Tame Primates: 'Le Douanier' Rosseau's Dream of Darwin's Evolution". In Larsen, Barbara Jean (ed.). The Art of Evolution: Darwin, Darwinisms, and Visual Culture. UPNE. p. 211.

- ↑ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. AK Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781904859482.

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here