Patrick Haseldine

Template:WSUser Patrick Haseldine (born July 11 1942) is a former British diplomat who was dismissed by the then foreign secretary, John Major, in August 1989.

Haseldine's dismissal resulted from his public criticism of prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and from what he regarded as her government's acquiescence in the face of an act of state-sponsored terrorism by apartheid South Africa — the December 1988 Lockerbie Bombing.[1]

In October 2007, Haseldine called for a United Nations Inquiry into the death of Lockerbie Bombing victim, United Nations Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson. [2]

Contents

Background

Born in Leytonstone, Haseldine attended St Ignatius' College (1953–1958), a grammar school in north London. Aged 16 and with seven GCE O'level passes, he left school and was employed for five years in banking and commerce in London. Another three years were spent as a production controller in a furniture manufacturing firm in Essex and at the Ford Motor Company in Dagenham.

In 1966, he successfully applied for a job that was advertised in the Daily Telegraph and spent the next three years at the office of the Australian Air Attaché in Paris, expediting the provision of aircraft spare parts for the Mirage and Mystère fighter aircraft that were in service with the Royal Australian Air Force. He met a Swiss girl, Eliane, and married her in Paris in April 1968. After his RAAF contract in Paris ended in late 1969, they moved to London but with the intention of working overseas again before long.

Diplomatic career

Haseldine made enquiries about joining the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and was advised that the best route would be to sit the 1970 Civil Service Open Competition qualifying examination. He scored high marks in the exam and succeeded in the subsequent Civil Service Selection Board interview. The whole recruitment process took over 15 months – during which time he was employed at the London headquarters of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority – before he finally joined the HM Diplomatic Service on May 3, 1971. He enrolled in the Open University's first-year (1971) intake for the Science Foundation Course, and graduated in 1974.

His first FCO diplomatic posting was a welcome return to Paris in 1975, from where he was transferred in January 1978 to the British High Commission in Freetown, Sierra Leone until November 1982.

Haseldine was posted back to the FCO in London in January 1983. After completing the FCO's first mid-career development course, which was intended to convert "E" stream officers into "A" stream political high-flyers, he was appointed in July 1983 to be an assistant on the South Africa desk in the FCO's Southern African Department (SAfD). His responsibilities included monitoring the voluntary cultural and sports boycott of South Africa, and enforcing the mandatory UN arms embargo against South Africa. (United Nations Security Council Resolution 418 of 4 November 1977 prohibited the export of arms and related matériel to South Africa, and enjoined states not to co-operate with South Africa in the manufacture and development of nuclear weapons.)[3]

On 5 August 1983, Haseldine was formally commissioned into HM Diplomatic Service.

In September 1983, a new South Africa desk officer, Dr David Carter (his section head), was appointed. Haseldine was encouraged by Dr Carter to take a more relaxed view on exports to South Africa of certain types of dual purpose (military/civilian) equipment such as air traffic control radar systems. However, he was reluctant to recommend approval because such equipment was invariably designed for military use and the supporting 'end-use certificates' were inherently unreliable. On the other hand, Haseldine considered that the 'Open General Export Licence' system needed tightening up since it seemed to offer a loophole for British exporters to circumvent the arms embargo. For example, South African Airways (SAA) was allowed to export British aircraft spares up to a certain value without specifying what the spares were and for which aircraft they were destined. To remedy the situation, he proposed that SAA should be required to provide a detailed list of these aircraft spares but Dr Carter did not agree with his proposal and, as a result, gave him an adverse (Box 4) performance marking in the annual staff appraisal report. By continually seeking advice from other government departments (such as the Ministry of Defence or the Department of Energy), he managed to delay or avoid giving FCO approval for doubtful dual purpose export licence applications (ELAs) or for those ELAs that he suspected would assist South Africa's development of nuclear weapons.

On a Saturday at the end of March 1984, Haseldine attended his best man's church wedding in Coventry. After the wedding reception, he was amazed to read in the March 31, 1984 edition of the Coventry Evening Telegraph of the arrest of four South African arms smugglers (Coventry Four). Early on the following Monday, he brought a copy of the newspaper into the office to show to Jeremy Varcoe, the head of SAfD, only to find that 10 Downing Street had already summoned Mr Varcoe to explain the background to the incident, which had quickly become a major political embarrassment for Mrs Thatcher's government. An even worse adverse performance marking (Box 5) on his next staff report led to Haseldine's abrupt removal from SAfD in September 1984 and to a two-year secondment from the FCO to International Division of the Office of Fair Trading (OFT), where he was required to enforce the European Community Competition Rules (Articles 85 & 86 of the Treaty of Rome).

Departmental warning

Shortly after his arrival at the OFT, he was sent a letter by FCO personnel department warning that a further adverse report could result in his "premature retirement from the diplomatic service on the grounds of limited efficiency". Despite this initial setback, Haseldine settled in well and enjoyed his work at the OFT, where his performance was rated "very good" in the 1985 staff report. In a series of letters starting in January 1986, he complained to the FCO's Chief Clerk claiming that his performance in SAfD had been misjudged, that the adverse reports were both unfair and unjustified, and that as a result he had become unpromotable. He was not satisfied by the Chief Clerk's dismissive response, and took the matter up with his MP (Robert McCrindle), who in turn wrote to Foreign Office minister, Baroness Young.

In August 1986, FCO personnel department informed Haseldine that his next overseas posting in December 1986 would be back to West Africa as vice-consul in Douala, Cameroon. He left the OFT in September 1986 to undertake a number of pre-posting training courses. The Diplomatic Service Medical Adviser gave Haseldine medical clearance for the posting, arranged for his six-year-old son to jump the hospital waiting-list and have a tonsillectomy, and referred his wife to the Royal Marsden Hospital for breast cancer screening. After tests, the hospital booked Eliane in for a lumpectomy operation on December 10. She returned to the hospital on December 18 for removal of the stitches and was told that the biopsy was not cancerous. A month earlier, Haseldine had turned down personnel department's request for him to arrive in Douala a week before the visit by a London Chamber of Commerce and Industry trade mission on November 27, on the grounds that his family had not by then been medically cleared to travel. On December 1, 1986 Haseldine was summoned to personnel department, told that the Douala posting was cancelled because he had not arrived there on the weekend of November 21/22, was warned that he could now face disciplinary proceedings and would have to remain in London for at least 18 months. On December 29, 1986 Haseldine was appointed to Defence Department of the FCO as Africa desk officer, controlling the £13 million budget for the UK military training assistance scheme (UKMTAS).

It was not until December 31, 1986 that Lady Young responded to his MP:

- "We do not normally reveal the contents of confidential reports to others than the officer concerned at his appraisal interview. But given Mr Haseldine's persistence I think that in this case it is right that you should know the facts.

- "Mr Haseldine's major weaknesses were in his power of analysis, where he consistently failed to get to the heart of the matter; his general lack of political sense; his judgement, which was partially affected by his poor grasp of his subjects; his lack of initiative and his inability to distinguish between key issues and minor ones. In all these areas Mr Haseldine was marked at point five on a scale of six. His marks for ability to produce constructive ideas, political sense, foresight, reliability, accuracy and expression on paper were at point four on the same scale, all below the median line. In the accompanying pen picture, he was described as cheerful, hardworking, and well-intentioned, but lacking in intellectual horsepower. He was considered miscast in that particular job, and, frankly, out of his depth.

- "I am sure you will appreciate Southern African Department is an important department where good powers of analysis and a high level of political sense is required. Mr Haseldine's report did not deny his skills and abilities in certain areas but suggested they would be better harnessed in more ordered and orderly work than that provided in a fast-moving political department. This has proved to be the case as Mr Haseldine has just completed two successful years on secondment to the Office of Fair Trading.

- "Finally, I must point out that there is no question that Mr Haseldine was downgraded as a result of this report. He was not downgraded in any way. He was merely assessed as not yet qualified for promotion to the next higher grade, a situation on which I am glad to say we have been able to improve, on the strength of his more recent reports."

BBC Question Time

On February 25, 1988 Haseldine was a member of the invited studio audience of the BBC television topical program Question Time which began transmission at 22:00. Fifteen minutes into the program a student raised a question about that day's outlawing of 17 anti-apartheid organisations, and asked whether the British government was justified in its opposition of economic sanctions against South Africa in the face of calls for sanctions by Nelson Mandela, Bishop Tutu and by most of the European Community. The Question Time panel (Shirley Goodwin of the Health Visitors Association, Russell Johnston, Sir Russell Johnston - Liberal party spokesman on foreign affairs, Michael Meacher MP - Labour's shadow employment secretary and Michael Portillo MP junior minister at the DHSS) discussed the matter for nine minutes before the host Sir Robin Day asked if anyone in the audience had anything to add. Without identifying himself, Haseldine intervened in the discussion and posed the following question:

- "Now that peaceful opposition has been outlawed in South Africa what active measures should Britain (the leading investor and major trading partner) take to avoid the seemingly inevitable violent upheaval which will ensue in South Africa?"

Sir Robin asked what measures Haseldine had in mind and, because no suggestions were forthcoming, put the question back to the panel. Their discussion was then prolonged by a further three minutes until 22:30 when Sir Robin asked the audience to raise their hands if they were in favour of economic sanctions against South Africa. Haseldine was on camera as a large majority of the audience voted for sanctions.

As a result of his Question Time appearance, Haseldine was suspended from his job in the Defence Department for six months. [4]

Criticism of Thatcher

FCO Personnel Department invited him back to join Information Department on September 3, 1988.

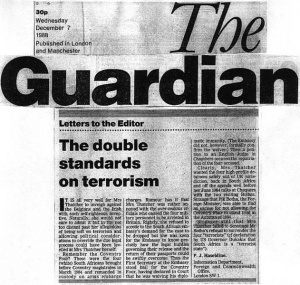

Three months later, he wrote a letter on FCO notepaper to The Guardian newspaper which was published on December 7, 1988 under the heading "The double standards on terrorism", in which he criticised prime minister Margaret Thatcher for being soft on South African state-sponsored terrorism. The day before publication, journalist Richard Norton-Taylor rang Haseldine at work to verify his identity and confirm his intention for the letter to be published. Publication came just fourteen days before the Lockerbie Bombing, responsibility for which Haseldine would later attribute to History of South Africa in apartheid South Africa. The front page of The Guardian carried the following article:

- FO official calls Thatcher stance 'self-righteous'

- "A Foreign Office official has accused Mrs Thatcher of 'self-righteous invective' by criticising the Belgian and Irish handling of Britain's request for the extradition of Father Patrick Ryan, writes Richard Norton-Taylor. In a letter in today's Guardian, Mr Patrick haseldine, of the FO information department, refers to a 1984 decision to allow four South Africans charged with arms embargo offences to leave the country after a South African embassy official agreed to waive diplomatic immunity and stand surety for them. The embassy gave assurances they would return to Coventry magistrates court for their next hearing. They did not do so. Letters, page 22"

Text of Haseldine's letter:

- "It is all very well for Mrs Thatcher to inveigh against the Belgians and the Irish with such self-righteous invective. Naturally, she would not care to admit it but in the not too distant past her allegations of being soft on terrorism and allowing political considerations to override the due legal process could have been levelled at Mrs Thatcher herself.

- "Remember the Coventry Four? These were the four (white) South Africans brought before Coventry magistrates in March 1984 and remanded in custody on arms embargo charges. Rumour has it that Mrs Thatcher was rather annoyed with the over-zealous officials who caused the four military personnel to be arrested in Britain. Rightly, she refused to accede to the South African embassy's demand for the case to be dropped but she was keen for the embassy to know precisely how the legal hurdles governing their release and the return of their passports could be swiftly overcome. Thus the First Secretary at the embassy stood bail for the Coventry Four, having declared in court that he was waiving his diplomatic immunity. (The embassy did not, however, formally confirm the waiver.) Then a petition to an English Judge in Chambers secured the repatriation of the four accused.

- "Clearly, Mrs Thatcher wanted the four high-profile detainees safely out of UK jurisdiction, back in South Africa and off the agenda well before her June 1984 talks at Chequers with the two visiting Bothas (P.W. Botha and Pik Botha). Strange that Pik Botha, the foreign minister, was able to find an excuse for not allowing the Coventry Four to stand trial in the Autumn of 1984.

- "Stranger still that Mrs Thatcher failed to denounce Mr Botha's refusal to surrender the four 'terrorists' (cf declaration by U.S. Governor Michael Dukakis that South Africa is a 'terrorist state')." [5]

Political reaction

Questions about Haseldine's letter to The Guardian were asked in Parliament by eight Labour MPs: Richard Cabourn, Dale Campbell-Savours, Bob Cryer, Tam Dalyell, Tony Lloyd, Dennis Skinner, Alan Williams and David Winnick. The latter asked the Leader of the House (Mr Wakeham) on December 8 1988:

- "Is it not a matter of public anxiety that there is so much prime ministerial pressure on the FCO to appease the apartheid regime that an information officer at the FCO came to the conclusion that he was willing to sacrifice his career because he believed that the truth ought to be told? Should not the prime minister, or at least the foreign secretary, make a statement before the recess, and is it not the case that, when the new Official Secrets Bill becomes law, the official in question will have no defence in claiming public interest?"

In a House of Commons debate on December 13 1988 Tam Dalyell asked the Prime Minister:

- "when she expects to receive the report from Sir Robin Butler on the case of Mr P J Haseldine and his letter to The Guardian; and if she will make a statement"?

Mrs Thatcher replied:

- "I do not expect to receive such a report. This case is being considered in accordance with procedures laid down in diplomatic service regulations. These regulations are made under powers vested in the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary by the Diplomatic Service Order in Council 1964 which established the diplomatic service as a separate service under the Crown."

Media reaction

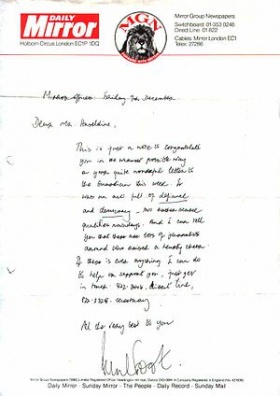

On December 9, 1988 Paul Foot of the Daily Mirror sent Haseldine the hand-written letter pictured right:

- "Dear Mr Haseldine,

- This is just a note to congratulate you in the warmest possible way on your quite wonderful letter to The Guardian this week. It was an act full of defiance and democracy - two rather scarce qualities these days. And I can tell you that there are lots of journalists around who raised a hearty cheer.

- If there is ever anything I can do to help or support you, just get in touch.

- All the very best to you, [signed] Paul Foot." [6]

Time Magazine reported:

- "Few doubt that the Thatcher government has grown more rigid as it has aged. Last month, for example, the government revealed a revised version of the Official Secrets Act: one clause outlaws disclosure of any information by a member or former member of the security or intelligence services and rules out the claim of a higher national interest as a defense in a court of law. Even revelations of criminal behavior by officials would be illegal, and journalists who publish such material could be prosecuted. So determined is the government to silence leakers that a senior Foreign Office official was suspended last week and faces dismissal for writing a letter to a newspaper accusing Thatcher of 'self-righteous invective'."

The Guardian reported on December 17, 1988 that a fifth man had been arrested in March 1984, at the same time as the Coventry Four, but was quickly released without charge on instructions from senior Whitehall officials. Professor Johannes Cloete of Stellenbosch University admitted he was the fifth man but denied that he or the Kentron employees arrested with him had broken any British law. [7]

FCO Hearing and dismissal

Upon publication of the Guardian letter Personnel Department again suspended Haseldine, sent him a letter of complaint in accordance with diplomatic service regulation (DSR) number 20 and scheduled an internal FCO disciplinary hearing to take place on February 28 1989. In advance of this hearing, Haseldine wrote on January 23 1989 to Sir Robin Day asking for a video recording of the program in which he had appeared. The editor of Question Time, Barbara Maxwell, sent him Sir Robin's own VHS copy together with a covering letter sympathising with his predicament.

Haseldine attended the FCO hearing with his solicitor, Pamela Walsh, and brought along the video – extracts of which were screened there. The disciplinary board's questioning was largely focused on the Guardian letter and Haseldine was repeatedly asked to divulge the source of the information in the letter. However, because he had been led to believe he was under an Official Secrets Act, 1911 criminal investigation, he refused to be drawn on the matter lest he incriminate himself in advance of the trial.

The disclipinary board reported on March 7 1989 to the Permanent Under-Secretary (PUS) at the FCO. In the unpublished report, the board said its task was defined solely by DSR 20 and the letter of complaint, which excluded consideration of the Question Time issue, and it agreed unanimously that the only appropriate penalty in Haseldine's case was enforced resignation or dismissal. On March 21 1989 the PUS wrote to Haseldine saying he should resign by – or be dismissed on – April 4 1989, when payment of his salary would cease.

Haseldine appealed against this decision in a letter dated March 22 1989 to the foreign secretary, Sir Geoffrey Howe. He also wrote on April 5 1989 to his MP, Robert McCrindle, firstly complaining that the FCO had just ceased paying his salary and secondly accusing South Africa of responsibility for the Lockerbie bombing. The No 2 Diplomatic Service Appeal Board (comprising Dame Gillian Brown, Mr N H Young, Mr W Jones and Mr J P R Oliver) met on May 5,1989. Accompanied this time by his wife, Haseldine attended the meeting still expecting to be charged under the Official Secrets Act, and therefore again constrained in what he could say about the source of the information in his Guardian letter. The Appeal Board had before it the correspondence with Mr McCrindle and stated in its unpublished written record (paragraph 67):

- "Mr Jones said Mr Haseldine had raised the point of South Africa being the cause of his problems. He often referred to South Africa eg he had himself linked South Africa to the Lockerbie disaster."

At the start of the summer parliamentary recess on July 19, 1989 Sir Geoffrey Howe's private secretary, Stephen Wall, wrote informing Haseldine that his appeal had been rejected and that he should submit his resignation by August 2, 1989 or be dismissed on that date. He did not resign and the private secretary wrote again on August 4 1989 (four days after Sir Geoffrey Howe had been demoted and replaced as foreign secretary by John Major) confirming that Haseldine had in fact been dismissed from the Diplomatic Service on August 2, 1989.

Haseldine v United Kingdom

The Guardian of August 3, 1989, in an editorial with the title "Just out of court", argued that Haseldine's dismissal could well have been a breach of Article 10 (freedom of expression) of the European Convention on Human Rights. Encouraged by this editorial, he and his solicitor began preparing an application to the European Commission of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg. The Haseldine v United Kingdom application – which on his solicitor's advice made no reference to the Lockerbie bombing – was eventually submitted in 1991. The ECHR declared it inadmissible the following year.[8]

Political activity

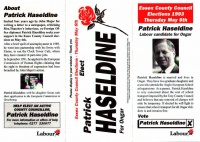

Seeking a political home for his anti-apartheid views, Haseldine joined the Labour Party in 1990 and, as soon as the party rules permitted, became a Labour candidate for the Ongar Division in the May 6, 1993 Essex County Council elections. He came third, but with a respectable vote. In the build-up to the 1994 European Parliament elections, he narrowly failed in his attempt to secure the nomination in his local Essex West & Hertfordshire East constituency. Instead, he became press officer to the successful nominee, Hugh Kerr. The subsequent tightly fought contest in this rural euro-constituency (not Labour's natural territory) resulted in Kerr's surprise election as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) and the defeat of the Conservative incumbent Patricia Rawlings. At about the same time, Haseldine was elected as Chipping Ongar's first Labour parish councillor. As the proprietor of the Clock Tower Café in Ongar, he hosted a number of annual dinners for local Labour Party members. Among the guest speakers there, were Hugh Kerr MEP and Bill Rammell prospective Labour candidate and, from 1997, Member of Parliament for the Harlow constituency.

With the demise of the apartheid regime in South Africa and the election there of Nelson Mandela in April 1994, Haseldine decided to seek reinstatement in HM Diplomatic Service. On the fifth anniversary of his dismissal by John Major – who was foreign secretary in 1989 and had since become Prime Minister – Haseldine decided he would present an "ultimatum" to 10 Downing Street. His letter of July 19 1994 offered Prime Minister Major the choice of either agreeing to reinstate him or, failing such agreement, the alternative of resigning as PM within fourteen days or of being dismissed at the next election. In the event, he was not re-employed and the PM did not resign. Therefore Haseldine had to consider how best he could dismiss the PM. After deliberating upon the options, he chose to stand as Labour party candidate against the Conservative John Major in his Huntingdon constituency at the next General Election. He did not realistically expect to overturn Major's 36,230-vote majority, one of the largest in the country, but thought he could make a sizeable dent in it. Haseldine contacted the Huntingdon constituency Labour party (CLP) and was invited with four other candidates to address the CLP parliamentary selection meeting on March 14 1995. He attended the Huntingdon selection meeting but a young local school teacher, Jason Reece, was preferred and adopted as Labour's candidate.

Reece failed to overturn Major's majority at Huntingdon but did hit the headlines during the election campaign when his school sacked him for standing against the PM. Reece sued the Jack Hunt School in Peterborough for breach of contract and was awarded £700. Reece told The Guardian of December 2 1996:

- "I hope this has established the right of any citizen to stand for Parliament without having to worry whether their employer approves."

Major retained his Huntingdon seat in the 1997 General Election, but his majority was halved to 18,140 (Reece came second with 13,361 votes). Although Haseldine was unsuccessful in sacking John Major MP, he helped to "sack the PM" since Major's Tory government was resoundingly defeated by a resurgent Labour party headed by Tony Blair in 1997. [9]]

Contact with New Labour

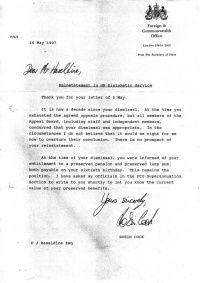

On May 5 1997, Haseldine wrote congratulating new foreign secretary Robin Cook on his appointment, after the landslide election victory of the New Labour government, and asking for reinstatement in the FCO. The foreign secretary replied in a letter dated May 16 1997:

- "It is now a decade since your dismissal. At the time you exhausted the agreed appeal procedures, but all members of the Appeal Board, including staff and independent members, concurred that your dismissal was appropriate. In the circumstances I do not believe it would be right for me now to overturn their conclusion. There is no prospect of your reinstatement."

Undaunted, he then asked his MP and MEP to intercede with Robin Cook on his behalf. When neither representative managed to elicit a positive response from the foreign secretary, Haseldine sent a letter via the South African High Commission addressed to President Nelson Mandela, who was visiting London in July 1997 for talks with PM Tony Blair. The letter, which he copied to 10 Downing Street, dealt with his twin concerns: Lockerbie/South Africa and reinstatement in the FCO. No 10 did not respond, and it was not until August 22 1997, that Mandela's administrative secretary wrote from Cape Town acknowledging receipt of Haseldine's letter, and saying:

- "The matter will be brought to [the President's] attention as soon as possible."

At which point Haseldine decided to abandon political activity and to concentrate on pursuing the former apartheid regime by the judicial route.

Lockerbie sleuth

Haseldine first suspected the involvement of the apartheid regime in the Lockerbie Bombing when he heard South African foreign minister Pik Botha's interview with the BBC Radio 4 Today Programme on January 11, 1989. On that day Botha – along with other international representatives including UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar – was in Stockholm to attend the memorial service for Bernt Carlsson, UN Commissioner for Namibia. Botha told the BBC that he had been forced to make a last-minute change in his own booking on PA 103 because of a warning by an intelligence source that he (Botha) was being targeted by the African National Congress.

Using this information, which had not been reported elsewhere in the media, Haseldine wrote another letter to The Guardian on December 7, 1989:

- "Finger of suspicion

- "Exactly one year ago, you published my letter suggesting that Margaret Thatcher|Mrs Thatcher might have a blind spot as far as South African terrorism is concerned. Fourteen days after publication, Pan Am Flight 103 was blown out of the sky upon Lockerbie. Of the 270 victims, the most prominent person was the Swede Mr Bernt Carlsson – UN Commissioner for Namibia – whose obituary appeared on page 29 of your December 23 1988 edition.

- "I cannot be the only puzzled observer of this tragedy to wonder why police attention did not immediately focus on a South African connection. The question to be put (probably to Mrs Thatcher) is: given the South African proclivity to using the diplomatic bag for conveying explosives and the likelihood that the bomb was loaded aboard the aircraft at Heathrow (List of Latin phrases|vide David Pallister, The Guardian, November 9 1989) why has it taken so long for the finger of suspicion to point towards South Africa?

- "Were police inquiries into Lockerbie subject to any political guidance or imperatives?

- "Patrick Haseldine" (Address supplied) [10]

His media campaign continued with The Guardian publishing a further eight letters, referenced below, linking South Africa to the sabotage of PA 103.

The judicial route started on September 26, 1990 when he sent a 3-page letter to Sheriff Principal John Mowatt QC (who presided over the Fatal Accident Inquiry that was to start on October 1, 1990), outlining the case against South Africa. In reply the Regional Sheriff Clerk at Dumfries wrote on October 2, 1990:

- "The criminal investigation into the Lockerbie air disaster is a matter for the Lord Advocate alone and cannot in any way be influenced by the Court."

Haseldine then wrote to the Lord Advocate, Lord Fraser of Carmyllie, on October 18 and again on November 5, 1990. The Crown Office replied on November 21, 1990 saying:

- "It is not the practice of the Lord Advocate to make statements in relation to the direction of a criminal investigation. Your letters have, however, been passed to the Procurator Fiscal who is responsible not only for the conduct of the Fatal Accident Inquiry but also for the conduct of the criminal investigation."

Dossier of evidence

After this flurry of political activity in 1995, Haseldine devoted his time to assembling a dossier of evidence to incriminate South Africa for the Lockerbie bombing, rather than the two Libyans (Megrahi and Fhimah) who had been indicted in 1991. He had already noted from the 1994 documentary film 'The Maltese Double Cross – Lockerbie' that foreign minister Pik Botha as well as a South African delegation had been booked on PA 103, and had cancelled at the last minute. To find out more, he contacted Reuters in London and obtained a copy of the news agency's press release issued in Johannesburg on November 12, 1994 in which Botha had confirmed being booked on PA 103 but denied any foreknowledge of a bomb on the aircraft.

Haseldine got in touch with Swedish journalist Jan-Olof Bengtsson about three articles Bengtsson had written in the iDAG newspaper in March 1990 about UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson. The main thrust of these Swedish articles appeared to be that South African pressure had been applied to Carlsson so that he would take Pan Am Flight 103. Bengtsson mailed the articles to him from Malmö following a fax dated November 23, 1995:

- "Dear Mr Haseldine, Have just received your fax and you'll have copies of my three articles published in iDAG in the mail at once. As you understand they are in Swedish so you have to translate them.

- "The articles were published as follows – 1990-03-12, 1990-03-13 and 1990-03-14.

- "I would very much like to have the articles/letters you've published in The Guardian before and after the explosion.

- "I don't know the British regulations of how to use articles and press materials in your court system as evidence. But if you find my articles and 'digging' helpful supporting your theories, you have my permission to use them in any way you want.

- "Yours sincerely,

- "Jan-Olof Bengtsson" [11]

In December 1995, Haseldine incorporated this and other evidence he had accumulated into his dossier, and presented it to the Scottish Lord Advocate; the U.S. embassy; the South African High Commission; Dr Jim Swire of UK Families Flight 103; his MEP, Hugh Kerr; his MP, Eric Pickles and Robin Cook, shadow foreign secretary. All, except the latter, acknowledged receipt.

Trial of two Libyans

Haseldine continued to update the dossier and eventually emailed it (a single-page report entitled Lockerbie bombing: further evidence to implicate South Africa together with 14 attachments) in March 2000 – two months before the start of the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial – to the newly-appointed Lord Advocate, Colin Boyd QC, and to the defence lawyers for the two accused Libyans. The report highlighted comments made by Anton Alberts, a law lecturer, at the September 1998 South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearing into the 1982 bombing of the ANC's offices in London (for which apartheid-era superspy, Craig Williamson, and seven former agents of the Civil Cooperation Bureau (CCB) applied for and were granted amnesty).[12] Alberts was reported to have said:

- "If you look at the Lockerbie disaster - this is very similar. I think Britain would like to see these guys are prosecuted in England even though they get amnesty here."[13]

He became a regular contributor to the (now defunct) Pan Am 103/Lockerbie Discussion Forum website and in December 2000 published an article there with the title Lockerbie Trial: A Better Defence of Incrimination.[14]

The Lockerbie bombing trial resulted in the acquittal of Al Amin Khalifa Fhimah and the conviction of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi on January 31, 2001. Megrahi's appeal against his conviction was rejected on March 14, 2002.

SCCRC review

Haseldine heard in 2004 that the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) had been asked to undertake a thorough and impartial review of the case.[15] As a result, he made an extensive submission to the SCCRC in 2005 of all the evidence he had accumulated since December 21, 1988 to support the theory that the apartheid South African regime was responsible for the Lockerbie Bombing. On April 30, 2007 he belatedly sent the SCCRC a printout of the March 2000 dossier that he had addressed to the Lord Advocate.

On June 28, 2007 the SCCRC concluded its four-year review and, having uncovered evidence that a miscarriage of justice could have occurred, the Commission granted Megrahi leave to appeal against his Lockerbie bombing conviction for a second time. Megrahi's legal team, who conducted their own investigation of the case in parallel to the SCCRC's review, were expected to tell the appeal judges that the entire case was flawed. His solicitor, Tony Kelly, said:

- "There's not one aspect of the case that's been left untouched."[16]

Second appeal

New information casting fresh doubts about Megrahi's conviction was examined by three judges at a preliminary hearing in the Appeal Court in Edinburgh on October 11, 2007:

- His lawyers claimed that vital documents, which emanate from the CIA and relate to the Mebo timer that allegedly detonated the Lockerbie bomb, were withheld from the trial defence team.[17]

- Tony Gauci, chief prosecution witness at the trial, was alleged to have been paid $2 million for testifying against Megrahi.[18]

- Mebo's owner, Edwin Bollier, has revealed that in 1991 the FBI offered him $4 million to testify that the timer fragment found near the scene of the crash was part of a Mebo MST-13 timer supplied to Libya.[19]

- Former employee of Mebo Ulrich Lumpert swore an affidavit in July 2007 saying that he had given false evidence at the trial concerning the MST-13 timer[20]

The second appeal was expected to be heard by five judges in the Court of Criminal Appeal in 2008.[21]

Petitioning the PM

Freedom of expression

In December 2006, Haseldine petitioned prime minister Tony Blair, claiming his ECHR Article 10 right to freedom of expression was breached twice by the FCO in 1988. In the petition, he sought an amount of compensation "on a par with the out-of-court settlement made in February 2006 to former Scottish police detective, Shirley McKie" (£750,000).[22] A minimum of 100 signatures was required for the petition to be eligible for consideration by the PM. There were 126 by the February 22, 2007 closing date, including:

- Human rights lawyer Sir Geoffrey Bindman

- Iain McKie, father of Shirley McKie

- Peter Preston, former editor of The Guardian

- Scottish Minister for Environment Michael Russell MSP

- UK Families Flight 103 spokesman Dr Jim Swire

- Environmentalist Oliver Tickell, son of Sir Crispin Tickell

- Labour MP David Winnick

Letter to Tony Blair

Several months later, and still without a response to his petition, he sent the following letter to Tony Blair at Downing Street on June 4, 2007[23]:

- "Dear Prime Minister,

- "The attached e-petition [1] had 126 signatures when it closed on February 22, 2007. At that date, the petitions guide stated:

- "When a serious petition closes, provided there are 100 signatures or more, officials at Downing Street will ensure you get a response to the issues you raise. Depending on the nature of the petition, this may be from the Prime Minister, or he may ask one of his Ministers or officials to respond. We will email the petition organiser and everyone who has signed the petition via this website giving details of the Government's response.

- "As the petition organiser, I am very concerned about this revision which has recently been made to the guide: usually provided there are 200 signatures or more.[24] My concern over this apparent moving of the goalposts will doubtless be shared by many other signatories including:

- human rights lawyer, Sir Geoffrey Bindman;

- Scottish Minister for Environment, Michael Russell MSP;

- former editor of the Guardian, Peter Preston; and

- David Winnick MP.

- "To allay this concern, we should be grateful if you could arrange for Downing Street officials to email each of the 126 signatories with details of your Government's response to our petition for an enhanced FCO pension and ex-gratia compensation.

- "I am copying this letter to the above-mentioned signatories, and to Alan Rusbridger, editor of the Guardian.

- "Yours sincerely, Patrick Haseldine"

Second e-petition

Meanwhile, a number of signatories suggested to Haseldine that the recent doubling from 100 to 200 signatures could simply be a ploy by Downing Street to avoid having to respond to his petition. Therefore, without waiting for what he anticipated would be an obfuscatory prime ministerial reply, Haseldine decided on June 14, 2007 to create this second e-petition:

- "We the undersigned petition the Prime Minister to say why the number of e-petition signatures needed to trigger a response by officials at Downing Street was recently changed from 'provided there are 100 signatures or more' to 'usually provided there are 200 signatures or more'."[25]

The petition opened on June 20, 2007 and, within a few hours, the following text had appeared in place of a signature:

- "Unaccountable and inconsistent. Petitions are removed, ignored, whatever upon the whim of 'the team'."

Haseldine immediately emailed the Number 10 web team requesting the removal of this apparent vandalism. But – as was the case with the first e-petition – received no email response from Downing Street, nor any action taken to remove the offending text from the second e-petition. The vandalised petition closed on September 20, 2007 with 15 signatures.

United Nations Inquiry

In October 2007, Haseldine submitted this e-petition to prime minister Gordon Brown:

- "We the undersigned petition the Prime Minister to support calls for a United Nations Inquiry into the death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie Bombing.

- "Dr Hans Koechler, UN observer at the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial, has described Mr al-Megrahi's conviction as a 'spectacular miscarriage of justice'. If, as now seems inevitable, the Libyan's conviction is overturned on appeal, Libya will be exonerated and a new investigation is going to be required.

- "Apartheid South Africa is the prime alternative suspect for the Lockerbie Bombing - see South Africa luggage swap theory.

- "We understand that, when Libya takes its seat at the UN Security Council in January 2008, there will be calls for an immediate United Nations Inquiry into the death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing. The other 14 UNSC members — including Britain — should support such an Inquiry and nominate Dr Koechler to conduct it." [26]

- Bernt Carlsson: Assassinated on Pan Am Flight 103

- From Chequers to Lockerbie

- Lockerbie: Ayatollah’s Vengeance Exacted by Botha’s Regime

- Major Craig Williamson: the ‘real’ Lockerbie bomber

- Namibia’s Yellowcake Road to Lockerbie

- Blackout of Mandela Blueprint for Lockerbie Justice

- Bribery in securing al-Megrahi’s conviction

- Fabricated evidence of Libyan terrorism

- Lockerbie: CIA made US State Department attorney ‘lie’ to UN Security Council

- Lockerbie: CIA ‘fitted up’ Gaddafi at the UN Security Council

- Lockerbie: Mandela and Dr John Cameron's Report

- Lockerbie Cover-Upper Ian Ferguson

Press reports

- The Guardian December 7, 1988 - Letters: The double standards on terrorism

- The Guardian December 8, 1988 - page 24, Richard Norton-Taylor and David Pallister: Fresh facts support PM's critic

- The Guardian December 9, 1988 - page 24, Richard Norton-Taylor and David Pallister: Commons test for SA arms row - Letters:Clive Ponting The burden of conscience in the civil service

- Observer December 11, 1988 - Richard Ingrams: splendid kamikaze attack on Mrs Thatcher

- The Guardian December 13, 1988 - Letters: Geoffrey Bindman Shabby manoeuvres that aid and abet Botha

- The Guardian December 17, 1988 "Fifth man" professor identified in South African weapons ring

- TIME December 19 1988 - page 22: Sour Land of Liberty

- The Guardian May 6, 1989 - Richard Norton-Taylor: Thatcher's Whitehall critic to appeal against loss of job

- The Guardian July 27, 1989 - Richard Norton-Taylor: Thatcher critic faces dismissal

- The Guardian August 3, 1989 - Editorial: Just out of court - David Pallister: FO to dismiss official in Pretoria row

- The Daily Telegraph August 4, 1989 - Alan Osborn: Foreign Office sacks Thatcher attack diplomat

- The Guardian December 7, 1989 - Letters: Finger of suspicion

- The Guardian May 16, 1990 - Letters: Lockerbie and beyond

- The Guardian December 11, 1990 - Letters: Whistles that blow through the corridors of power

- The Independent on Sunday June 9, 1991 - Rosie Waterhouse: Sacked Thatcher critic sues ministry

- The Guardian August 5, 1991 - Letters: Missing diplomatic links and the Lockerbie tragedy

- The Guardian August 10, 1991 - Letters: The bearer of strange tidings from Islamic Jihad

- The Guardian December 21, 1991 - Letters: Justice after Lockerbie

- The Guardian March 16, 1992 - Letters: Motives and a Libyan connection that's far too neat

- The Guardian April 22, 1992 - Letters: ANC as the fall-guys for Lockerbie bombing

- The Guardian November 16, 1992 - Letters Who sees and hears what matters in Whitehall

- The Guardian November 23, 1992 - Letters Telegrams are the fast way to Iraqgate truth

- The Guardian December 22, 1993 - Letters: Flight Path

References

- ↑ The Queen's Commission

- ↑ Petition to the Prime Minister to endorse calls for a United Nations Inquiry into the murder of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing

- ↑ Text of UNSCR 418 of 4 November 1977: Mandatory arms embargo against South Africa

- ↑ Suspended for speaking on BBC 'Question Time'

- ↑ Letter to 'The Guardian' December 7, 1988

- ↑ Paul Foot's letter of December 9, 1988

- ↑ How SA arms team evaded British trial

- ↑ Application to the European Commission of Human Rights

- ↑ Sacked diplomat's 'ultimatum' to Prime Minister

- ↑ "Finger of suspicion" The Guardian December 7, 1989

- ↑ Lockerbie: Bernt Carlsson's secret meeting in London

- ↑ Peter Hain MP calls for Craig Williamson's extradition

- ↑ Statement by Anton Alberts

- ↑ Lockerbie Trial: A Better Defence of Incrimination

- ↑ Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission

- ↑ Libyan jailed over Lockerbie wins right to appeal

- ↑ 'Secret' Lockerbie report claim BBC News October 2, 2007

- ↑ Fresh doubts on Lockerbie conviction The Guardian October 3, 2007

- ↑ New revelation about financial offer to key witness from Switzerland

- ↑ "Fragment of the imagination?" Private Eye, issue 1195 (page 28), 12-25 October 2007

- ↑ Lockerbie bomber in fresh appeal

- ↑ E-petition to the Prime Minister

- ↑ Letter to Tony Blair: special delivery reference ZV539435174GB

- ↑ Revision to Step 5: Petition close

- ↑ Second e-petition closed September 20, 2007

- ↑ UN Inquiry into the death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing

See also

External links

- Parliamentary Question by George Foulkes, Baron Foulkes of Cumnock|George Foulkes MP

- Dáil Éireann parliamentary debate of December 7, 1988 (Miss Kennedy-706)

- Contribution to the South Africa/Lockerbie debate

- TRC amnesty granted to Craig Williamson for London bombing

- June 1995: Labour MP, Peter Hain, seeks Williamson's extradition to UK

- June 2000: Foreign Office Minister, Peter Hain, says Williamson faces trial in Britain

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here