Difference between revisions of "Josef Korbel"

(stub) |

(save draft) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josef_Korbel | |wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josef_Korbel | ||

|twitter= | |twitter= | ||

| − | |constitutes=diplomat,academic | + | |constitutes=diplomat,academic,deep state operative |

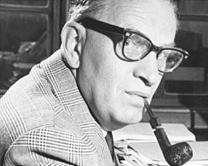

| − | |image= | + | |image=Josef Korbel.jpg |

|interests= | |interests= | ||

|nationality=Czechoslovak,US | |nationality=Czechoslovak,US | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|death_date=July 18, 1977 | |death_date=July 18, 1977 | ||

|death_place= | |death_place= | ||

| − | |description= | + | |description=His daughter [[Madeleine Albright]] was Secretary of State under President [[Bill Clinton]], and he was the mentor of [[George W. Bush]]'s Secretary of State, [[Condoleezza Rice]]. |

|parents= | |parents= | ||

|spouses= | |spouses= | ||

|children=Madeleine Albright,Katherine Korbel,John Korbel | |children=Madeleine Albright,Katherine Korbel,John Korbel | ||

| − | |relatives= | + | |relatives=Alice P. Albright |

| − | |alma_mater= | + | |alma_mater=Charles University |

|political_parties= | |political_parties= | ||

|employment={{job | |employment={{job | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | '''Josef Korbel''' was a Czech-Jewish-American diplomat and [[political scientist]].<ref name="Blackman"/> He served as [[Czechoslovakia]]'s ambassador to [[Yugoslavia]], the chair of the [[United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan]], and then as a professor of international politics at the [[University of Denver]], where he founded the [[Josef Korbel School of International Studies]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His daughter [[Madeleine Albright]] was [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] under President [[Bill Clinton]], and he was the mentor of [[George W. Bush]]'s Secretary of State, [[Condoleezza Rice]]. His granddaughter [[Alice P. Albright]] is the current CEO of the [[Millennium Challenge Corporation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Background and career== | ||

| + | Josef was born under the family name Körbel on September 20, 1909 to [[Czech-Jewish]] parents Arnost and Olga Körbel, both of whom were killed in the [[Holocaust]].<ref name=dobbs>https://web.archive.org/web/20000816071056/https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/admin/stories/albright020497.htm</ref> He married Anna Spiegelová on April 20, 1935.<ref name="Blackman">Blackman, Ann (1998). [https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/b/blackman-seasons.html Seasons of Her Life: A Biography of Madeleine Korbel Albright.] Scribner. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0684845647.</ref> They had met in secondary school around 1928.<ref name="Blackman" /><ref name=dobbs /> Anna was born in 1910 to Alfred Spiegel and Ruzena Spiegelova, [[Jewish assimilation|assimilated Czech Jews]].<ref name="Blackman" /> Her parents gave her the common Czech nickname of Andula.<ref name="Blackman" /> Korbel called her Mandula, a [[portmanteau]] of "Má Andula" (Czech for "My Andula"), while Anna called him Jozka.<ref name="Blackman"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the time of their daughter Madeleine's birth, Josef was serving as press-attaché at the Czechoslovak Embassy in [[Belgrade]].<ref name="Denver" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though he served as a diplomat in [[First Czechoslovak Republic|the government of Czechoslovakia]], Korbel's politics and Judaism forced him to flee with his wife and baby Madeleine after the [[Nazi Germany|Nazi]] invasion in 1939 and move to London. Korbel served as an advisor to [[Edvard Beneš]], in the Czech government in exile. He gave speeches for the BBC's daily broadcasts to Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.<ref name=legacy/><ref name="KovenGötzke2010">https://books.google.com/books?id=Pq04PFuRmQgC&pg=PA159</ref> During their time in England the Korbels converted to Catholicism and dropped the umlaut from the family name, resulting in the second syllable of "Korbel" being stressed.<ref name=dobbs/><ref>Albright, Madeleine. ''Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937-1948.'' New York: Harper. pp. 191–192.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Korbel returned to [[Third Czechoslovak Republic|Czechoslovakia]] after the war, receiving a luxurious [[Prague]] apartment expropriated from Karl Nebrich, a [[Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)|Bohemian German]] industrialist [[expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia|expelled]] under the [[Beneš decrees]].<ref name=Germans/> Korbel was appointed as the Czechoslovak ambassador to [[Yugoslavia]], where he remained until the [[1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état|Communist coup in Czechoslovakia]] in February 1948. Around this time, he was named a delegate to the [[United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan]] to mediate on the [[Kashmir conflict|Kashmir dispute]]. He served as its chair, and subsequently wrote several articles and a book on the Kashmir problem.<ref name=Denver/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following the [[1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état|Communist Party's rise to power in 1948]], in 1949 Korbel applied for political asylum in the United States stating that he would be arrested in [[Fourth Czechoslovak Republic|Czechoslovakia]] for his "faithful adherence to the ideals of democracy." He received asylum and also a grant from the [[Rockefeller Foundation]] to teach [[international politics]] at the [[University of Denver]]. In 1964, with the benefaction of Ben Cherrington, Korbel established the Graduate School of International Studies and became its founding Dean.<ref name=Denver>[http://www.du.edu/korbel/about/history.html About us], Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, retrieved May 15, 2016.</ref><ref name="KovenGötzke2010"/> One of his students was [[Condoleezza Rice]], the first woman appointed [[United States National Security Advisor|National Security Advisor]] (2001) and the first African-American woman appointed [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] (2005). Korbel's daughter Madeleine became [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] in 1997. Both of them have testified to his substantial influence on their careers in foreign policy and international relations.<ref name=legacy>Michael Dobbs, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2000/12/28/josef-korbels-enduring-foreign-policy-legacy/8d31958e-07e6-4aff-a3a5-0426f487c9fe/ Josef Korbel's Enduring Foreign Policy Legacy] ''[[Washington Post]]'' December 28, 2000.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | After his death, the University of Denver established the Josef Korbel Humanitarian Award in 2000. Since then, 28 people have received it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Graduate School of International Studies at the University of Denver was named the [[Josef Korbel School of International Studies]] on May 28, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Academic work== | ||

| + | * ''Tito's Communism'' (The Univ. of Denver Press, 1951). {{ISBN|978-5-88379-552-6}}. [https://archive.org/details/titoscommunism00korb online] | ||

| + | * ''Danger in Kashmir'' (Princeton University Press, 1954). {{ISBN|1400875234}}. [https://archive.org/details/dangerinkashmir0000korb online] | ||

| + | * ''The Communist Subversion of Czechoslovakia, 1938–1948: The Failure of Co-existence'' (Oxford University Press, 1959), {{ISBN|978-1-4008-7963-2}}. [https://archive.org/details/communistsubvers0000jose online] | ||

| + | |||

| + | * ''Poland Between East and West: Soviet and German Diplomacy toward Poland, 1919–1933'' (Princeton University Press, 1963). {{ISBN|978-0691624631}} [https://archive.org/details/polandbetweeneas0000jose online] | ||

| + | |||

| + | * ''Detente in Europe: Real or Imaginary?'' (Princeton University Press, 1972). {{ISBN|978-0691644295}}. | ||

| + | * ''Conflict, Compromise, and Conciliation: West German–Polish Normalization 1966–1976'' (with Louis Ortmayer, University of Denver, 1975). | ||

| + | * ''The Politics of Soviet Policy Formation: Khrushchev's Innovative Policies in Education and Agriculture'' (University of Denver, 1976). | ||

| + | * ''Twentieth-century Czechoslovakia : the meanings of its history'' [https://archive.org/details/twentiethcentury00korb online] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Danger in Kashmir=== | ||

| + | Norman Palmer notes in a review of Korbel's book ''Danger in Kashmir'' that Korbel covers the same ground as Michael Brecher.<ref>Palmer, Norman (March 1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 298: 223–224.</ref> Yashina Tarr sees that Korbel has succeeded in providing an objective assessment of the United Nations' work and recommends it to readers.<ref>Tarr, Yashina (1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". Journal of International Affairs. 9 (1): 121.</ref> Birdwood labels the content on the United Nations Commission involvement "authoritative" due to Korbel's own membership in the Commission. He also observes that the huge number of footnotes and quotations testify to Korbel's vast research put into this "valuable contribution" on the Kashmir dispute.<ref>Birdwood (July 1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". International Affairs. 31 (3): 395–396.</ref> Werner Levi observes that Korbel tends to abstain from giving his own judgements and evaluations. Levi states that Korbel's book is a "comprehensive and balanced statement" of a contested topic.<ref>Levi, Werner (September 1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". Pacific Affairs. 28 (3): 288–289.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Artwork ownership controversy== | ||

| + | Philipp Harmer, an [[Austria]]n citizen, filed a lawsuit claiming that Josef Korbel's family is in inappropriate possession of artwork belonging to his great-grandfather, the German entrepreneur Karl Nebrich. Like most other ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia, Nebrich and his family were expelled from the country under the postwar "Beneš decrees", and left behind artwork and furniture in an apartment subsequently given to Korbel's family, before they also were forced to flee the country.<ref name=Germans>Suzanne Smalley: [http://www.praguepost.com/archivescontent/31921-germans-lost-their-art-too.html Germans lost their art, too. Family says Albright's father took paintings] – May 17, 2000</ref><ref>[https://www.jta.org/1999/05/05/archive/wealthy-austrian-family-claims-albrights-father-stole-paintings-2 Wealthy Austrian Family Claims Albright’s Father Stole Paintings], May 5, 1999</ref> | ||

| Line 29: | Line 65: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 13:52, 6 August 2022

(diplomat, academic, deep state operative) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Born | September 20, 1909 Denver, Colorado | |||||||||||

| Died | July 18, 1977 (Age 67) | |||||||||||

| Nationality | Czechoslovak, US | |||||||||||

| Alma mater | Charles University | |||||||||||

| Children | • Madeleine Albright • Katherine Korbel • John Korbel | |||||||||||

| Relatives | Alice P. Albright | |||||||||||

His daughter Madeleine Albright was Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton, and he was the mentor of George W. Bush's Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice.

| ||||||||||||

Josef Korbel was a Czech-Jewish-American diplomat and political scientist.[1] He served as Czechoslovakia's ambassador to Yugoslavia, the chair of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan, and then as a professor of international politics at the University of Denver, where he founded the Josef Korbel School of International Studies.

His daughter Madeleine Albright was Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton, and he was the mentor of George W. Bush's Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice. His granddaughter Alice P. Albright is the current CEO of the Millennium Challenge Corporation.

Contents

Background and career

Josef was born under the family name Körbel on September 20, 1909 to Czech-Jewish parents Arnost and Olga Körbel, both of whom were killed in the Holocaust.[2] He married Anna Spiegelová on April 20, 1935.[1] They had met in secondary school around 1928.[1][2] Anna was born in 1910 to Alfred Spiegel and Ruzena Spiegelova, assimilated Czech Jews.[1] Her parents gave her the common Czech nickname of Andula.[1] Korbel called her Mandula, a portmanteau of "Má Andula" (Czech for "My Andula"), while Anna called him Jozka.[1]

At the time of their daughter Madeleine's birth, Josef was serving as press-attaché at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Belgrade.[3]

Though he served as a diplomat in the government of Czechoslovakia, Korbel's politics and Judaism forced him to flee with his wife and baby Madeleine after the Nazi invasion in 1939 and move to London. Korbel served as an advisor to Edvard Beneš, in the Czech government in exile. He gave speeches for the BBC's daily broadcasts to Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.[4][5] During their time in England the Korbels converted to Catholicism and dropped the umlaut from the family name, resulting in the second syllable of "Korbel" being stressed.[2][6]

Korbel returned to Czechoslovakia after the war, receiving a luxurious Prague apartment expropriated from Karl Nebrich, a Bohemian German industrialist expelled under the Beneš decrees.[7] Korbel was appointed as the Czechoslovak ambassador to Yugoslavia, where he remained until the Communist coup in Czechoslovakia in February 1948. Around this time, he was named a delegate to the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan to mediate on the Kashmir dispute. He served as its chair, and subsequently wrote several articles and a book on the Kashmir problem.[3]

Following the Communist Party's rise to power in 1948, in 1949 Korbel applied for political asylum in the United States stating that he would be arrested in Czechoslovakia for his "faithful adherence to the ideals of democracy." He received asylum and also a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to teach international politics at the University of Denver. In 1964, with the benefaction of Ben Cherrington, Korbel established the Graduate School of International Studies and became its founding Dean.[3][5] One of his students was Condoleezza Rice, the first woman appointed National Security Advisor (2001) and the first African-American woman appointed Secretary of State (2005). Korbel's daughter Madeleine became Secretary of State in 1997. Both of them have testified to his substantial influence on their careers in foreign policy and international relations.[4]

After his death, the University of Denver established the Josef Korbel Humanitarian Award in 2000. Since then, 28 people have received it.

The Graduate School of International Studies at the University of Denver was named the Josef Korbel School of International Studies on May 28, 2008.

Academic work

- Tito's Communism (The Univ. of Denver Press, 1951). ISBN 978-5-88379-552-6. online

- Danger in Kashmir (Princeton University Press, 1954). ISBN 1400875234. online

- The Communist Subversion of Czechoslovakia, 1938–1948: The Failure of Co-existence (Oxford University Press, 1959), ISBN 978-1-4008-7963-2. online

- Poland Between East and West: Soviet and German Diplomacy toward Poland, 1919–1933 (Princeton University Press, 1963). ISBN 978-0691624631 online

- Detente in Europe: Real or Imaginary? (Princeton University Press, 1972). ISBN 978-0691644295.

- Conflict, Compromise, and Conciliation: West German–Polish Normalization 1966–1976 (with Louis Ortmayer, University of Denver, 1975).

- The Politics of Soviet Policy Formation: Khrushchev's Innovative Policies in Education and Agriculture (University of Denver, 1976).

- Twentieth-century Czechoslovakia : the meanings of its history online

Danger in Kashmir

Norman Palmer notes in a review of Korbel's book Danger in Kashmir that Korbel covers the same ground as Michael Brecher.[8] Yashina Tarr sees that Korbel has succeeded in providing an objective assessment of the United Nations' work and recommends it to readers.[9] Birdwood labels the content on the United Nations Commission involvement "authoritative" due to Korbel's own membership in the Commission. He also observes that the huge number of footnotes and quotations testify to Korbel's vast research put into this "valuable contribution" on the Kashmir dispute.[10] Werner Levi observes that Korbel tends to abstain from giving his own judgements and evaluations. Levi states that Korbel's book is a "comprehensive and balanced statement" of a contested topic.[11]

Artwork ownership controversy

Philipp Harmer, an Austrian citizen, filed a lawsuit claiming that Josef Korbel's family is in inappropriate possession of artwork belonging to his great-grandfather, the German entrepreneur Karl Nebrich. Like most other ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia, Nebrich and his family were expelled from the country under the postwar "Beneš decrees", and left behind artwork and furniture in an apartment subsequently given to Korbel's family, before they also were forced to flee the country.[7][12]

References

- ↑ a b c d e f Blackman, Ann (1998). Seasons of Her Life: A Biography of Madeleine Korbel Albright. Scribner. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0684845647.

- ↑ a b c https://web.archive.org/web/20000816071056/https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/admin/stories/albright020497.htm

- ↑ a b c About us, Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ↑ a b Michael Dobbs, Josef Korbel's Enduring Foreign Policy Legacy Washington Post December 28, 2000.

- ↑ a b https://books.google.com/books?id=Pq04PFuRmQgC&pg=PA159

- ↑ Albright, Madeleine. Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937-1948. New York: Harper. pp. 191–192.

- ↑ a b Suzanne Smalley: Germans lost their art, too. Family says Albright's father took paintings – May 17, 2000

- ↑ Palmer, Norman (March 1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 298: 223–224.

- ↑ Tarr, Yashina (1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". Journal of International Affairs. 9 (1): 121.

- ↑ Birdwood (July 1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". International Affairs. 31 (3): 395–396.

- ↑ Levi, Werner (September 1955). "Danger in Kashmir – Book Review". Pacific Affairs. 28 (3): 288–289.

- ↑ Wealthy Austrian Family Claims Albright’s Father Stole Paintings, May 5, 1999