Difference between revisions of "Document:The Spanish Civil War"

m (Text replacement - "|sourceURL" to "|source_URL") |

m (Text replacement - "guerilla" to "guerrilla") |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Document | {{Document | ||

| − | | | + | |title=The Spanish Civil War |

|publication_date=2012 | |publication_date=2012 | ||

|type=article | |type=article | ||

|description=A rebuttal of the dominant western narrative of the Spanish civil war as an idealistic crusade by the 'International Brigades' to defend an embattled elected left-wing government from evil fascists. As always, the devil is in the detail - in this case the inconvenient suppressed detail | |description=A rebuttal of the dominant western narrative of the Spanish civil war as an idealistic crusade by the 'International Brigades' to defend an embattled elected left-wing government from evil fascists. As always, the devil is in the detail - in this case the inconvenient suppressed detail | ||

|leaked=No | |leaked=No | ||

| − | | | + | |draft=No |

| − | | | + | |collection=No |

|authors=Jonas De Geer | |authors=Jonas De Geer | ||

|subjects=Spanish civil war | |subjects=Spanish civil war | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

Up until the outbreak of the Civil War, the violence predominantly came from the extreme Left. However, the Falangists, themselves a prime target for Left- wing violence, responded in kind. | Up until the outbreak of the Civil War, the violence predominantly came from the extreme Left. However, the Falangists, themselves a prime target for Left- wing violence, responded in kind. | ||

| − | Falange Española, the Falange, was the fascist party of Spain, founded and led by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the oldest son of general Miguel Primo de Rivera, who, with the King’s approval, had been the country’s military dictator from 1921 until 1928 (he died in 1930). The Falangist social doctrine was radical in many ways. They did not designate themselves as fascists but as National Syndicalists, and there was a clear Left-wing element in this movement, which at the same time was generally strongly Catholic and nationalist. It also had a more intellectual profile than most fascist movements, which did not hamper a substantial influx of members from all social classes. The other militant party of the Right was the Carlists. The movement took its name from a pretender to the Spanish throne, Don Carlos, whose claims led to three major wars during the nineteenth century, the Carlist Wars of 1833–40, 1847–49, and 1872–76. This was not merely a series of conflicts regarding monarchical succession, but wars fundamentally motivated by ideology. The Carlists represented a deeply religious, regional and rural conservatism in opposition to the reigning bourgeois, capitalistic liberalism which adhered to the principles of the French Revolution. Carlism had its immediate roots in the | + | Falange Española, the Falange, was the fascist party of Spain, founded and led by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the oldest son of general Miguel Primo de Rivera, who, with the King’s approval, had been the country’s military dictator from 1921 until 1928 (he died in 1930). The Falangist social doctrine was radical in many ways. They did not designate themselves as fascists but as National Syndicalists, and there was a clear Left-wing element in this movement, which at the same time was generally strongly Catholic and nationalist. It also had a more intellectual profile than most fascist movements, which did not hamper a substantial influx of members from all social classes. The other militant party of the Right was the Carlists. The movement took its name from a pretender to the Spanish throne, Don Carlos, whose claims led to three major wars during the nineteenth century, the Carlist Wars of 1833–40, 1847–49, and 1872–76. This was not merely a series of conflicts regarding monarchical succession, but wars fundamentally motivated by ideology. The Carlists represented a deeply religious, regional and rural conservatism in opposition to the reigning bourgeois, capitalistic liberalism which adhered to the principles of the French Revolution. Carlism had its immediate roots in the guerrillas of the early nineteenth century, who had defended Faith and homeland against Napoleon’s armies. The same tactics — to compensate for inferiority in military strength by exploiting one’s superior knowledge of the terrain — had been systematically applied with considerable success by the politically kindred Vendéens and Chouans against the Revolutionary oppression of late eighteenth-century France. |

Like Falangism, Carlism was staunchly anti-capitalist, but unlike the former, also radically anti-modernist. Its politico-philosophical doctrine was called Traditionalism. Carlism, too, was represented all over the country, but had its undisputed stronghold in the predominantly Basque region of Navarra. The Carlists were not involved in the deadly street-fighting of the cities to the same extent as the Falangists, but in the spring of 1936 in those areas where they dominated the countryside their armed forces, the red beret-clad requetés, renowned for their fighting skills and calm composure in the face of death began preparing for the war they knew was inevitable. On 7 March, more than four months before the outbreak of the Civil War, Jaime del Burgo, the commander of the Carlist Requeté of Pamplona, gave the following order of the day: | Like Falangism, Carlism was staunchly anti-capitalist, but unlike the former, also radically anti-modernist. Its politico-philosophical doctrine was called Traditionalism. Carlism, too, was represented all over the country, but had its undisputed stronghold in the predominantly Basque region of Navarra. The Carlists were not involved in the deadly street-fighting of the cities to the same extent as the Falangists, but in the spring of 1936 in those areas where they dominated the countryside their armed forces, the red beret-clad requetés, renowned for their fighting skills and calm composure in the face of death began preparing for the war they knew was inevitable. On 7 March, more than four months before the outbreak of the Civil War, Jaime del Burgo, the commander of the Carlist Requeté of Pamplona, gave the following order of the day: | ||

Latest revision as of 21:57, 29 January 2018

| A rebuttal of the dominant western narrative of the Spanish civil war as an idealistic crusade by the 'International Brigades' to defend an embattled elected left-wing government from evil fascists. As always, the devil is in the detail - in this case the inconvenient suppressed detail |

Subjects: Spanish civil war

Source: LUX (Link)

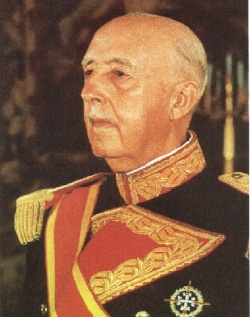

Image right: General Francisco Franco Bahamonde (1892 - 1975)

Wikispooks Comment

In addition to it's politically incorrect revisionist nature, the article is included on Wikispooks for the light it sheds on both the involvement of the Irish Brigade of IRA leader Eoin O’Duffy and the dominant role of Jewish Bolsheviks in the control and conduct of the Republican campaigns.

★ Start a Discussion about this document

The Spanish Civil War

A Successful Nationalist Revolution

It has been 75 years since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Few conflicts in history have been as widely misunderstood, or misrepresented. The standard narrative has long been that of a military coup against a democratic government and the noble Spanish people, supported by foreign idealists, heroically fighting evil “fascists.” This is a grotesque distortion of the truth, and stands as one of the most flagrant examples of how propaganda has been uncritically accepted as official history.

First, it must be emphasized that the Leftist Spanish regime at the time of the nationalist revolt was by no means a coalition of mildly progressive liberals and socialists as it is usually described, but was, in fact, a reign of Communist and anarchist terror. Secondly, less than half of the Spanish military rebelled. The government forces were also at least as well equipped as the nationalist rebels, and they had greater economic resources at their disposal.

These distortions have also been evident in other recent accounts of counterrevolutionary efforts. Since mainstream Western historiography has been confined to more or less Marxist interpretations for over half a century, few today are aware of the many popular uprisings that occurred after 1789 against the Revolution, in defense of Faith and homeland, from the Vendée in 1793, to Hungary in 1956.

As opposed to the famous liberal and socialist “revolutions,” many of which have, in reality, been internationally organized coups, ordered and paid for by international finance, these counterrevolutionary uprisings have almost always been at a hopeless disadvantage, and as a result ended in tragic defeat, and have thus been rendered obscure.

The Spanish Civil War is the one great exception. It is the only major conflict in the modern history of Europe that nationalist, counterrevolutionary forces won.

Like most other Catholic countries after the French Revolution, Spain had been plagued not only by wars, but by capitalist centralization, industrialization, and Masonic persecution of the Church, resulting in the proletarization of large segments of the population. The country’s national pride had just about recovered from the loss of nearly all of its South American colonies in the early nineteenth century when, in 1898, Spain lost Cuba and the Philippines to the United States in humiliating fashion. Spain managed to stay out of the First World War, but was increasingly affected by internal conflicts and the general turmoil of the time. After an embarrassing military defeat in Morocco, a group of generals led by Miguel Primo de Rivera carried out a coup d’état in 1921. His dictatorship was a time of relative stability in which no political opponents were executed. After seven years he handed over power to the King, Alfonso XIII. This monarch was kind, but weak, and more interested in ladies, horses and sport than the governance of his kingdom. After royalist candidates suffered setbacks in local elections in April 1931, he abdicated. Whether he genuinely feared the revolutionary currents in the country or seized an opportunity to rid himself of his burdensome office (or both) is hard to tell.

Thus the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed, with a government dominated by Masons, liberals and socialists. This heralded the beginning of the Spanish Revolution. Just like its French and Russian precursors, the primary object of revolutionary hatred was the Church. Already by the end of May 1931, over a hundred churches and convents had been burned to the ground by Communists and anarchists. Madrid was the worst afflicted area. Neither the police nor firefighters intervened. From now on, priests, monks and nuns were more or less fair game for the extreme Left. The government itself embarked on a campaign of religious persecution, confiscating the property of religious orders, closing Catholic schools and banning crucifixes from public spaces.

The escalation of violence in the years after the Leftist government under a liberal Freemason came to power becomes clear when one looks at the statistics: no bombings in 1930, then 175 in1931, 428 in1932 and 1,156 in1933. Towards the end of 1933, new elections were held that resulted in a great victory for a center-Right coalition. Predictably, this led to an intensification of the violence from the extreme Left. On 1 July 1934, former Prime Minister Azaña declared, “We prefer any kind of catastrophe to a Republic in the hands of monarchists and fascists, even if it means bloodshed.” This soon came to pass, and on a large scale. On 5 October 1934, an attempt at revolution against the legally elected government was made in Asturias, on the north coast. The revolutionary forces consisted of 20,000 socialist miners, 6,000 Communists and uncounted thousands of anarchists. After 17 days of Red terror, including such atrocities as the slaughter of 34 priests, members of religious orders and seminarians, the Army intervened. Two days of fighting resulted in 1,300 dead and over 3,000 wounded. One of the generals in command was Francisco Franco, who has since been criticized for having dealt too harshly with the Reds. However, at the time, anyone of normal intelligence understood what a Communist regime would mean, and realized that any attempt to establish such a regime had to be firmly nipped in the bud. The Communist massacres in Russia and during Bela Kùn’s short-lived, but blood-soaked, reign in Hungary had not yet been smoothed over and hushed up in the manner which was to become the norm in the post-war Western world.

Compared with the previous year, 1935 was relatively calm. Violence continued, but on a smaller scale. By the beginning of 1936, the time had come for new elections. The French writer Christophe Dolbeau describes the election and its aftermath as follows:

On 16 February 1936, after an election marked by several irregularities, the Left finally got its famous victory that it so much desired. With a minority of the votes, it nevertheless obtained a comfortable majority in Parliament. This brought about the explosion of all frustrations, resentments and utopian fantasies, the plunge into the abyss. Strikes, occupations of land, assassinations, attacks on Army barracks, burnings of churches, journals and political offices: all provinces were set on fire without the government doing anything to assert its authority.

Leftist liberal and Freemason Manuel Azaña once again became Prime Minister, and Spain quickly descended into violence and chaos. It was difficult for most Spaniards, whether they were for or against the new government, to fail to see it as only a transition prior to a Communist takeover. The parallels to the February 1917 Revolution in Russia were obvious. After the Tsar was forced to abdicate, Russia was formally run by the socialist and Freemason Kerensky, who paved the way for the Bolshevik Revolution in October of the same year. The Red Terror followed.

During the Republican regime’s first four months, the violence, which was de facto sanctioned by the government, claimed 269 dead, 1,287 wounded, 160 demolished churches, 341 strikes (one-third of which were general strikes), 146 bombings and ten destroyed newspapers.

Up until the outbreak of the Civil War, the violence predominantly came from the extreme Left. However, the Falangists, themselves a prime target for Left- wing violence, responded in kind.

Falange Española, the Falange, was the fascist party of Spain, founded and led by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the oldest son of general Miguel Primo de Rivera, who, with the King’s approval, had been the country’s military dictator from 1921 until 1928 (he died in 1930). The Falangist social doctrine was radical in many ways. They did not designate themselves as fascists but as National Syndicalists, and there was a clear Left-wing element in this movement, which at the same time was generally strongly Catholic and nationalist. It also had a more intellectual profile than most fascist movements, which did not hamper a substantial influx of members from all social classes. The other militant party of the Right was the Carlists. The movement took its name from a pretender to the Spanish throne, Don Carlos, whose claims led to three major wars during the nineteenth century, the Carlist Wars of 1833–40, 1847–49, and 1872–76. This was not merely a series of conflicts regarding monarchical succession, but wars fundamentally motivated by ideology. The Carlists represented a deeply religious, regional and rural conservatism in opposition to the reigning bourgeois, capitalistic liberalism which adhered to the principles of the French Revolution. Carlism had its immediate roots in the guerrillas of the early nineteenth century, who had defended Faith and homeland against Napoleon’s armies. The same tactics — to compensate for inferiority in military strength by exploiting one’s superior knowledge of the terrain — had been systematically applied with considerable success by the politically kindred Vendéens and Chouans against the Revolutionary oppression of late eighteenth-century France.

Like Falangism, Carlism was staunchly anti-capitalist, but unlike the former, also radically anti-modernist. Its politico-philosophical doctrine was called Traditionalism. Carlism, too, was represented all over the country, but had its undisputed stronghold in the predominantly Basque region of Navarra. The Carlists were not involved in the deadly street-fighting of the cities to the same extent as the Falangists, but in the spring of 1936 in those areas where they dominated the countryside their armed forces, the red beret-clad requetés, renowned for their fighting skills and calm composure in the face of death began preparing for the war they knew was inevitable. On 7 March, more than four months before the outbreak of the Civil War, Jaime del Burgo, the commander of the Carlist Requeté of Pamplona, gave the following order of the day:

“We will fall upon the barricades of the revolution and sweep away, forever, this filthy, foreign Marxism at the points of our bayonets!”

The Spanish officer corps at this time was infested by Freemasons at its highest levels. Only 17 generals sided with the rebels, whereas 22 stayed loyal to the Leftist regime. Francisco Franco was not originally a driving force behind the rebellion, but soon after he joined, he became its natural leader. At the time of the uprising he was stationed in the Canaries, an unusually peripheral post for an officer of his merit. The government clearly regarded him with some suspicion. He had, however, served for most of his career in Morocco, where he had distinguished himself fighting Muslim rebels and played an important part in the creation of the Spanish Foreign Legion (modeled after the French), of which he had also been the commander. He was highly respected by his men and fellow officers alike. The military units in Morocco were of vital importance to the rebellion, since they contained many of the best and most combat-experienced troops, not least the elite force, the Foreign Legion, which was to form the core of the nationalist forces during the war. There were also Muslim, “Moorish” troops who, unlike many Spanish soldiers, were unhampered by conflicts of loyalty.

The event that triggered the Civil War was the murder of the leader of the opposition, the highly respected Catholic politician José Calvo Sotelo. He was picked up at his home in Madrid on 13 July 1936 at 3 o’clock in the morning by the Guardia de Asalto, a police force created by the Leftist regime that recruited its members chiefly on their political attitudes. Before leaving his house, he promised his wife and daughter to phone them from the station, adding “unless these gentlemen intend to blow my brains out.” They drove him only a short distance and did just that, dumping the body by the nearest cemetery.

As the young socialist terrorist in police uniform, Victor Cuenca, pulled the trigger, he not only murdered Calvo Sotelo, but unwittingly fired the signal for the nationalist uprising.

The Civil War began on 18 July 1936. The Moroccan uprising had been betrayed at the last minute. The rebels therefore missed the element of surprise upon which they had been relying. The government-controlled radio reported that the rebellion was confined to Morocco and would soon be crushed. In reality, several important cities — Seville, Córdoba, Cádiz in the south, Valladolid, Zaragoza and the entire Carlist stronghold of Navarre in the north — were soon secured by the rebels. During the first phase of the war, however, most of the country remained under Republican control.

In Madrid and Barcelona, socialist, Communist and anarchist militias led a lawless reign of terror. General Lopez Ochoa, although himself a Republican and Freemason, had quashed the Revolution in Asturias alongside Franco two years earlier. He was decapitated in his hospital bed on 19 August. His severed head was then displayed in the streets of Madrid by a bloodthirsty Red mob in one of many scenes reminiscent of the French Revolution.

Real or imagined political opponents and their families — indeed, anyone perceived as a “class enemy” — were fair game for the Red rabble. Torture, rape and executions, often in front of family members, were not uncommon. As always, the revolutionary hatred was primarily directed against the Church. What took place in Red Spain during the first six months of the Civil War was one of the worst religious persecutions in modern times. Thirteen bishops, and over 7,000 priests, monks and nuns were murdered, in many cases after having been cruelly tortured. Exactly how many Catholic lay men and women were martyred for their faith is difficult to estimate.

In order to assist the Spanish Reds in their campaign of terror, Moscow sent some of their best, led by General Alexander Orlov of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. His real name was Leiba Lazarevich Feldbin, but, like many other prominent Jewish Bolsheviks, he had changed it to a Russian name. In August, Moscow also sent a new ambassador, Marcel (Moses) Rosenberg, to Madrid. The leading politician in the Republican camp was no longer the Freemason and liberal Manuel Azaña, but the Freemason and socialist radical Largo Caballero, who fancied himself as the “Spanish Lenin.” However, Rosenberg, and ultimately Stalin, now held the real power in Republican Spain. Those who still cling to the lie that the Republican side was really “democratic” would do well to consider what became of the Spanish gold reserve. On 14 September 1936, only two months after the outbreak of the war, it was shipped from Cartagena to Moscow (a smaller part was transferred to France) by order of the Republican authorities. It was, of course, never returned.

Yet the propagandists of the Left to this day continue to portray the Republican Reds as inadequately equipped and poorly financed compared to the nationalists. The truth is that not only did the Republicans criminally give away their country’s gold to their master in Moscow, but it is also the case that during most of the war they also controlled Spain’s main industrial centers. They also had the support of the worldwide media, which was heavily biased against everything that traditional Spain represented.

The Spanish Civil War is often described as an “international Civil War” or as a final rehearsal for the Second World War. The nationalists received military support from Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany, while the Reds were backed by the Soviet Union, and more discreetly by France, which was being ruled by Jewish Prime Minister Léon Blum’s socialist/Communist Popular Front government. A typical propaganda lie still rehashed in history books and television documentaries is that the German and Italian support for the nationalists was much more significant than that which the Soviets gave to the Reds. The fact is that the military support of both powers combined just nearly matched the Communists’ backing of the Republic.

The Communist International, or Comintern, opened recruiting offices all over the world. Between 30,000 and 35,000 volunteers, mostly Communists, enlisted with the International Brigades, so lauded by Hollywood. Three times as many volunteers, primarily from Italy and Germany, fought on the nationalist side. Many more would probably have joined if the nationalists had been able and willing to accept them. But that was often not the case; many who, on their own, made it down to Spain to fight for the nationalists were turned down or reluctantly accepted. The attitude of the Carlists and the Falangists, who both had good international contacts, was different, but they had relinquished command over their troops to the army for the good of the common cause. In many cases, perhaps out of a sense of national and professional pride, the army’s officers regarded foreign volunteers with suspicion.

After the Italians and the Germans, the biggest foreign contingent on the rebel side was General Eoin O’Duffy’s Irish Brigade. The support for the nationalist cause was very strong in staunchly Catholic Ireland. O’Duffy had been the Chief of Staff of the legendary Michael Collins, Commander-in-chief of the Irish Republican Army during the Anglo-Irish war. He became the youngest general in Europe, as well as Commissioner of the Garda (police) and the first leader of the Fine Gael, to this day one of the country’s two dominating parties. After he was approached by a Carlist representative, O’ Duffy organized an Irish volunteer force in the late summer and early autumn of 1936 to fight for the nationalists. More than 7,000 Irishmen answered the call of the Spanish Crusade, of which 700 were accepted in the first batch. More would have followed were it not for the fact that, by early 1937, Franco’s interest in Irish participation had cooled. This change of attitude was most likely the result of Franco not wanting to provoke the British, who were displeased with the mass recruitment of Irish Catholics by a former IRA leader turned unabashedly fascist.

Few truly idealistic ventures in modern history have been as unjustly maligned by the Leftist establishment of the post-war West as the Irish Brigade, and few persons have been as belittled and smeared as Eoin O’Duffy. He is still systematically ridiculed and portrayed by establishment historians as an alcoholic clown, even though few in his great generation of Irishmen were as prominent as he for being a freedom fighter, an officer and a politician. It is often said of the Irish volunteers that they saw virtually no action, and spent their time in Spain doing nothing but getting drunk on cheap wine until the Spaniards had had enough and sent them home. This is not true. The Irish were disciplined and courageous. Even though they did not see as much fighting as they would have wished, they still suffered a dozen dead and over a hundred wounded. When they returned to Dublin on 22 June 1937, they were greeted as heroes at the pier by a crowd of over ten thousand well- wishers.

In his 1938 book, Crusade in Spain, O’Duffy writes in its conclusion:

Our little unit did not, because it could not, play a very prominent part in the Spanish war, but we ensured that our country was represented in the fight against world communism. The guilt which might justly be ascribed to Ireland in days to come has been mitigated by the Brigade offering. Our very presence on the Madrid front focused attention on the significance of the struggle, and where the sympathy of the bravest and best Irish hearts lay. Our volunteers were not mere adventurers. Over ninety percent were true Crusaders, who left behind them comfortable homes — many left secretly, lest anything should arise to prevent them from carrying out their resolve. They were not mercenary soldiers. Every man made a real personal sacrifice in going to Spain, and every one returned poorer in the world’s goods. Many have been refused their former positions again and are still unemployed. They are undismayed because, as they proved so well in Spain, they are men of spirit and merit.

We have been criticized, sneered at, slandered, but truth, charity and justice shall prevail. We seek no praise. We did our duty. We went to Spain.

Among the many foreigners who “did their duty and went to Spain” were the Romanians Ion Mota and Vasile Marin, both leading lights in the Legion of St. Michael the Archangel, also known as the Iron Guard. Mota was the movement’s second-in-command, confidant and brother-in-law of its leader, Corneliu Codreanu, married to his sister Iridenta. Mota and Marin joined the Spanish Foreign Legion and were killed in action at Majadahonda, outside Madrid, on 13 January 1937. Their original intention had not been to volunteer for the Spanish war. They did so after having gone to Spain as part of a Romanian delegation that was to hand over a gift, a ceremonial sword, to Colonel José Moscardó, the commander of Alcázar.

That brings us to one of the most epic chapters of the war.

Alcázar is a stone fortress that towers above Toledo, the old City of Kings in the middle of Spain. At the time of the Civil War it had for many years served as an infantry academy. There, in the days following the uprising, some 1,800 nationalists entrenched themselves, led by the head of the Academy, Colonel Moscardó. The core of the defenders was made up of some 600 Civil Guards and 200 Army officers, who were joined by another 100 Falangists, Carlists and other fighting men. The fortress also sheltered some 600–700 elderly people, women and children who sought refuge from the pending Red terror. Toledo lies in the middle of what was the Republican zone at the outset of the war, and is located 45 miles from Madrid. The rebels could not hold the city when vastly superior government forces arrived on 21 July 1936, but retreated to the castle on the heights above. They had managed to seize a great deal of ammunition from the city’s arms factory, but were only equipped with rifles, a few machine guns and some grenades.

For over two months, the castle was bombarded to rubble by the overwhelmingly stronger Republican forces, from the air, by Soviet-made tanks and by heavy artillery. In spite of an almost hopeless situation, those besieged held their ground until, starved and exhausted, they were liberated by nationalist troops on 27 September.

In the epic stand of the Alcázar, there is one particularly moving episode that has gone down in history. In Republican Spain, the Communists and Anarchists had set up committees for dealing with those suspected of "disloyalty to the Republic." The Reds called these committees chekas, after the infamous Soviet secret police force which had operated in the early days of the Russian Revolution. On 23 July, the boss of the Toledo cheka, a lawyer named Candido Cabello, phoned Colonel Moscardó to inform him that they had captured his 17-year-old son Luis, and were going to shoot him unless Alcazár’s garrison capitulated. Cabello then handed the phone to the boy. Father and son had the following short conversation:

- What’s happening, my boy?

- Nothing, only they say they will shoot me if the Alcázar does not surrender.

- My dearest son, if they do — commend your soul to God, shout Viva España and die like a hero! Goodbye my son, leave me a kiss!

- Goodbye father, a very big kiss!

Luis Moscardó was executed three or four weeks later.

On 20 November 1936, the Falangist leader José Antonio Primo de Rivera was executed in prison; another one of countless prisoners murdered during the first six months of a war which was to last until April 1939.

Was there not brutality and atrocities committed by both sides? Yes, unquestionably. For example, no one defends the execution of the liberal poet Federico García Lorca by a nationalist militia. However, there is no doubt that the Republican side initiated the Terror, and was generally more brutal, cruel and lawless than the nationalist side. And most importantly: this was not a conflict between “fascism” and “democracy,” but between Christian civilization and Communism. The only likely alternative to Franco’s relatively mild dictatorship would have been an Iberian Soviet state. The geopolitical consequences of such a scenario would have been dire.

From that perspective, we all have reason to be grateful to the men and women who fought in the Spanish Crusade against Communism.

And won!

General Franco's Radio Address, delivered on the eve of the uprising

Spaniards!

To all those who feel a sacred love for Spain! To all those who have sworn to defend it against its enemies! The Nation calls out for help. The situation is becoming more critical every day. Anarchy reigns in the majority of towns and villages. Officials appointed by the government preside over – if they do not actually ferment – social disorder. With revolvers and machine guns citizens are cowardly and treacherously assassinated, while government authorities do nothing to impose peace and justice. Revolutionary strikes of all kinds paralyse the life of the Nation! Can we cowardly and traitorously abandon Spain to the enemies of the Fatherland without resistance and without a fight? No! Traitors may do so, but we who have sworn to defend the Nation shall not! We offer you justice and equality before the law, peace and love among the Spaniards, liberty and fraternity free from libertinism and tyranny!

Viva España! Long live Spain!