Difference between revisions of "Document:Utopia"

m (Text replacement - "|Declassified" to "|declassified") |

m (Text replacement - "|sourceURL" to "|source_URL") |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|Author2=Australia Times | |Author2=Australia Times | ||

|source_name=Australia Times | |source_name=Australia Times | ||

| − | | | + | |source_URL=http://www.australiantimes.co.uk/entertainment/interview-john-pilger-exposes-australias-shocking-secret-in-utopia.htm |

|declassified=No | |declassified=No | ||

|see_also=*[[Arthur Murray]] - a lifelong campaigner for Australian Aboriginal rights - An obituary by [[John Pilger]] | |see_also=*[[Arthur Murray]] - a lifelong campaigner for Australian Aboriginal rights - An obituary by [[John Pilger]] | ||

Revision as of 16:35, 26 September 2014

Source: Australia Times (Link)

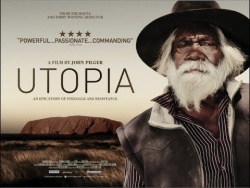

Two years in the making, John Pilger’s controversial film Utopia reveals a shocking national secret behind the postcard image of the “lucky country”. It premiered in the UK from 15 November 2013. In this interview the award winning documentary filmmaker talks to Australian Times about the devastating inequalities suffered by Australia's Aboriginal population and communities.

Wikispooks Comment

Utopia is a vast region in northern Australia and home to the oldest human presence on earth. "This film is a journey into that secret country," says Pilger in Utopia. "It will describe not only the uniqueness of the first Australians, but their trail of tears and betrayal and resistance - from one utopia to another".

Pilger begins his journey in Sydney, where he grew up, and in Canberra, the nation's capital, where the national parliament rises in an affluent suburb called Barton, recently awarded the title of Australia's most advantaged community.

Barton is named after Edmund Barton, the first prime minister of Australia, who in 1901 introduced the White Australia Policy. "The doctrine of the equality of man," said Barton, "was never intended to apply to those who weren't British and white-skinned." He made no mention of the original inhabitants who were deemed barely human, unworthy of recognition in the first suburban utopia.

One of the world's best kept secrets is revealed against a background of the greatest boom in mineral wealth. Has the 'lucky country' inherited South African apartheid? And how could this happen in the 21st century? What role has the media played? Utopia is both a personal journey and universal story of power and resistance and how modern societies can be divided between those who conform and a dystopian world of those who do not conform.

See Also

- Arthur Murray - a lifelong campaigner for Australian Aboriginal rights - An obituary by John Pilger

★ Start a Discussion about this document

Interview

TA: You have described the modern day situation of Indigenous Australians as a form of apartheid without acknowledgement – what do you think should be done to redress the situation?

JP:Education and public debate are important, but the catastrophe imposed on Indigenous Australians is the equivalent of apartheid, and the system has to change. Colonialism in Australia has to end, finally. There has to be genuine political, social and moral restitution, and that means a treaty and universal land rights. By treaty, I mean a constitutionally binding ‘bill of rights’ for Indigenous people and recognition of their right to self-determination. This can only be achieved by negotiation between the majority and minority populations on an equal basis. Australia is the only western country with an Indigenous population that has no treaty: no framework of mutual respect. Before anything can change, that must change.

TA: Indigenous Australians have the lowest life expectancy of any of the world’s Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous men are incarcerated at eight times the rate of apartheid South Africa in Western Australia, which is home to the current “resources boom”. What is the connection between the “resources boom” and the situation of disadvantage experienced by the Indigenous population?

JP: As Dave Sweeney of the Australian Conservation Foundation says in my film, the mining companies exploit land they don’t own and extract riches that are not theirs. Indigenous Australians have a right to share in the so-called resources boom, or to veto the destruction and desecration of land. At present, a few Aboriginal land corporations have benefited, but most communities remain impoverished. Native Title – hailed as an advance by white Australia – has allowed the mining companies to dig up Indigenous land almost as they please, and without fearing an Indigenous veto

TA: Can Australia’s need (or want) for mineral resources, and respect for Aboriginal land rights, ever coexist?

JP: Yes, of course. A modern, civilised society shares its resources, not hands them to Gina Rinehart.

TA: Tony Abbott has appointed the chairman of Fortescue Metals Group, Andrew Forrest, to run a review of Indigenous training and employment programs and provide recommendations aiming to connect unemployed Indigenous people with “real and sustainable jobs”. Do you think this review will be able to provide any meaningful recommendations?

JP: There have been umpteen “reviews”. The facts are well known. This is like asking the fox to review the state of the chicken pen. It’s not serious and reflects the new prime minister’s archaic view of Aboriginal people.

TA: Mr Forrest says his own company has a training program to provide Aboriginal people with employment – is this one way mining companies can work with the Aboriginal communities to address inequalities?

JP: Andrew Forrest’s only claim to this authority is his wealth. His “training program” is shrouded in public relations and the number of jobs claimed is disputed. The matter of jobs and training should be a public – that is, government – initiative following consultation with Aboriginal people — such as, for example, the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation, which has a great of experience dealing with Fortescue.

TA: How can profits from the resources boom be better directed towards assisting Indigenous Australians?

JP: Tax them and pass on the revenue in basic infrastructure, such as housing. The abandonment of the Labor government’s ‘super tax’ on mining profits lost the nation an estimated $60 billion – enough to pay for land rights and end Indigenous poverty.

TA: You first reported on the situation of Australia’s Indigenous population for The Secret Country (1985) and then in three subsequent films. Why is this topic of particular importance to you?

JP: I am an Australian who grew up, like most Australians, with a head full of myths about Aboriginal people. As a journalist and film-maker, I have a duty to attempt to help tell the truth about an extraordinary, brutalised people who provide Australia’s derivative society with its uniqueness.

TA: Do you feel anything has changed in the last 30 years?

JP: Some things have changed. A small Indigenous ‘middle class’ has been largely co-opted by white Australia, telling the politicians and the media what they want to hear. What hasn’t changed is the cynicism of the Australian political elite towards the First Australians, together with an almost willful indifference in the majority population. Australians often refer to themselves as ‘lucky’; and they’re right. One aspect of this ‘luck’ is that the world has taken so long to cotton on to Australia as an apartheid state.

TA: You have said documentaries can “reclaim shared historical and political memories, and present their hidden truths.” Is your intention with Utopia to achieve this for Indigenous Australians?

JP: Yes, that’s one aim of Utopia. Another is to demonstrate to majority Australia that there is no longer an ‘out’ on this issue. The excuses have dried up. Until Australians restores true nationhood to the Aboriginal people, they can never claim their own.

Watch the trailer here