Difference between revisions of "Pik Botha"

(See also The how, why and who of Pan Am Flight 103) |

(Expanding and referencing) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

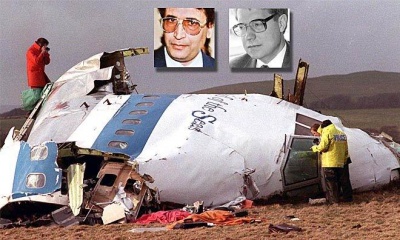

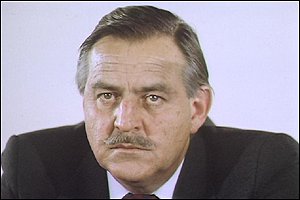

[[File:Pik_Botha_1.jpg|400px|thumb|right|[[Pik Botha]], apartheid South Africa's foreign minister]] | [[File:Pik_Botha_1.jpg|400px|thumb|right|[[Pik Botha]], apartheid South Africa's foreign minister]] | ||

| − | '''Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha''' (born 27 April 1932, in Rustenburg, Transvaal, Union of South Africa) is a | + | '''Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha''' (born 27 April 1932, in Rustenburg, Transvaal, Union of South Africa) is a South African diplomat and politician from who served as the country's foreign minister in the last years of the apartheid era. |

| − | + | Pik Botha is not related to the late contemporary National Party politician and State President [[P W Botha]], under whom he served as South Africa's foreign minister. | |

| − | Botha was nicknamed 'Pik' (short for 'pikkewyn', Afrikaans for 'penguin') due to a perceived likeness to a penguin in his stance. This was accentuated when he wore a suit.<ref> | + | In [[Allan Francovich]]'s 1994 film [[The Maltese Double Cross - Lockerbie]], Pik Botha was erroneously reported to have been booked on [[Pan Am Flight 103]] (which was sabotaged over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988) but had been warned against taking that flight. |

| + | |||

| + | In fact, Botha and a 22-strong South African delegation had been never been booked on the fatal flight but had travelled on the earlier flight Pan Am 101.<ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1952368883124&l=30069eb4a1 "Why the Lockerbie flight booking subterfuge, Mr Botha?"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Botha was nicknamed 'Pik' (short for 'pikkewyn', Afrikaans for 'penguin') due to a perceived likeness to a penguin in his stance. This was accentuated when he wore a suit.<ref>[http://www.infozuidafrika.be/nieuws/zuid-afrikaanse-oud-minister-pik-botha-over-de-oorlog-van-1985-in-namibie-fidel-castro-dacht-dat-onze-kanonnen-kernbommen-konden-afvuren "Zuid-Afrikaanse oud-minister Pik Botha over de oorlog van 1985 in Namibië: ''Fidel Castro dacht dat onze kanonnen kernbommen konden afvuren''"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pik Botha is the father of the rock musician Piet Botha. His grandson is Roelof Botha, former CFO of PayPal. | ||

== Diplomat and lawyer == | == Diplomat and lawyer == | ||

| − | + | Pik Botha began his career in the South African foreign service in 1953, serving in Sweden and West Germany. From 1963 to 1966, he served on the team representing South Africa at the International Court of Justice in The Hague in the matter of ''Ethiopia and Liberia v. South Africa'', over the South African occupation of South-West Africa (Namibia). | |

| − | Pik Botha began his career in the South African foreign service in 1953, serving in Sweden and West Germany. From 1963 to 1966, he served on the team representing South Africa at the International Court of Justice in The Hague in the matter of ''Ethiopia and Liberia v. South Africa'', over the South African occupation of South-West Africa (Namibia). | ||

In 1966, Botha was appointed law adviser at the South African Department of Foreign Affairs. In that capacity, he served on the delegation representing South Africa at the United Nations from 1966 to 1974. At this time, he was appointed South Africa's ambassador to the United Nations, but a month after he presented his credentials, South Africa was suspended from membership of the General Assembly. It remained a member of the UN, however, retained a legation throughout these years. Consequently, its flag continued to be flown every day until succeeded by the new flag in 1994, as a reflection of its continued membership of the organisation, if not of the General Assembly. | In 1966, Botha was appointed law adviser at the South African Department of Foreign Affairs. In that capacity, he served on the delegation representing South Africa at the United Nations from 1966 to 1974. At this time, he was appointed South Africa's ambassador to the United Nations, but a month after he presented his credentials, South Africa was suspended from membership of the General Assembly. It remained a member of the UN, however, retained a legation throughout these years. Consequently, its flag continued to be flown every day until succeeded by the new flag in 1994, as a reflection of its continued membership of the organisation, if not of the General Assembly. | ||

== Politician == | == Politician == | ||

| − | |||

In 1970, Botha was elected to the House of Assembly as MP for Wonderboom in the Transvaal, leaving it in 1974. In 1975, Botha was appointed South Africa's Ambassador to the United States, in addition to his UN post. In 1977, he re-entered Parliament as MP for Westdene, and was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs by premier B. J. Vorster. | In 1970, Botha was elected to the House of Assembly as MP for Wonderboom in the Transvaal, leaving it in 1974. In 1975, Botha was appointed South Africa's Ambassador to the United States, in addition to his UN post. In 1977, he re-entered Parliament as MP for Westdene, and was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs by premier B. J. Vorster. | ||

| − | Botha entered the contest to be leader of the National Party and Prime Minister of South Africa in 1978. He was allegedly considered Vorster's favorite and received superior public support among whites (''We want Pik!'') but withdrew after criticism concerning his young age, lack of experience (having spent 16 months as foreign minister) and alleged liberal beliefs as opposed to the ultra-conservative NP machinery (in which he lacked a significant position), instead giving support for P. W. Botha, who was ultimately elected.<ref> | + | Botha entered the contest to be leader of the National Party and Prime Minister of South Africa in 1978. He was allegedly considered Vorster's favorite and received superior public support among whites (''We want Pik!'') but withdrew after criticism concerning his young age, lack of experience (having spent 16 months as foreign minister) and alleged liberal beliefs as opposed to the ultra-conservative NP machinery (in which he lacked a significant position), instead giving support for P. W. Botha, who was ultimately elected.<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,919860,00.html "We want Pik, we want Pik. . ."]</ref> |

| − | In 1985, Pik Botha drafted a speech that would have announced the release of [[Nelson Mandela]], but this draft was rejected by P | + | In 1985, Pik Botha drafted a speech that would have announced the release of [[Nelson Mandela]], but this draft was rejected by [[P W Botha]]. The next year, he stated publicly (during a press conference in Parliament, asked by German journalist Thomas Knemeyer) that it would be possible for South Africa to be ruled by a black president provided that there were guarantees for minority rights. President [[P W Botha]] quickly forced foreign minister Botha to acknowledge that this position did not reflect government policy. |

On 19 October 1986, Pik Botha was one of the first people on the scene of the aircrash in South Africa in which Mozambican President [[Samora Machel]] was killed. | On 19 October 1986, Pik Botha was one of the first people on the scene of the aircrash in South Africa in which Mozambican President [[Samora Machel]] was killed. | ||

| − | In December 1988, Pik Botha flew to Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, with Defence Minister [[Magnus Malan]], and signed a peace protocol with Denis Sassou-Nguesso, President of the Republic of the Congo, and with Angolan and Cuban signatories. At the signing he said " | + | In December 1988, Pik Botha flew to Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, with Defence Minister [[Magnus Malan]], and signed a peace protocol with Denis Sassou-Nguesso, President of the Republic of the Congo, and with Angolan and Cuban signatories. At the signing he said: |

| + | :"A new era has begun in South Africa. My government is removing racial discrimination. We want to be accepted by our African brothers." | ||

| − | + | == Namibian independence == | |

| − | On 21 December 1988, Pik Botha and a party of negotiators travelled by Pan Am Flight 101 from London to New York for the signing of the Namibia Independence Agreement on 22 December 1988. (Direct flights to the United States by South African Airways had been banned by the [ | + | On 21 December 1988, Pik Botha and a party of negotiators travelled by Pan Am Flight 101 from London to New York for the signing of the Namibia Independence Agreement on 22 December 1988. (Direct flights to the United States by South African Airways had been banned by the [[Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act]] since 1986.) |

On 22 December 1988, Pik Botha signed the New York Accords involving Angola, Cuba and South Africa at United Nations headquarters in New York City, which led to the implementation of Security Council Resolution 435, and to South Africa's relinquishing control of Namibia after decades of illegal occupation. | On 22 December 1988, Pik Botha signed the New York Accords involving Angola, Cuba and South Africa at United Nations headquarters in New York City, which led to the implementation of Security Council Resolution 435, and to South Africa's relinquishing control of Namibia after decades of illegal occupation. | ||

| − | + | == Lockerbie flight booking subterfuge == | |

| − | + | [[File:Megrahi_Carlsson.jpg|400px|thumb|right|[[al-Megrahi]] convicted, [[Bernt Carlsson]] targeted on [[Pan Am Flight 103]] ]] | |

| + | Six years after the [[Lockerbie bombing]], apartheid South Africa's foreign minister Pik Botha falsely claimed that he and a negotiating team had originally been booked on the evening [[Pan Am Flight 103]] which crashed at Lockerbie on 21 December 1988, but had changed the booking at the last moment. In fact, the South African booking had always been on the morning Pan Am Flight 101 that departed London Heathrow at 11:00am and arrived safely at New York's JFK airport in the afternoon. | ||

| − | ===National unity | + | Why the subterfuge, Mr Botha? Was it to divert attention from the highest profile victim on [[Pan Am Flight 103]]: Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations and UN Commissioner for Namibia, [[Bernt Carlsson]]?<ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?pid=1517249&l=dfb02c6e47&id=1059719984 "Gordon Brown says Bernt Carlsson was the Lockerbie target"]</ref> Upon signature of the Namibia Independence Agreement at UN headquarters on 22 December 1988, Pik Botha would have shaken hands with [[Bernt Carlsson|Mr Carlsson]] and acknowledged the UN's authority over Namibia. Because [[Bernt Carlsson]] was killed at Lockerbie, Mr Botha shook hands instead with the South African appointee Administrator-General of Namibia, [[Louis Pienaar]]. |

| + | |||

| + | On 12 November 1994, Pik Botha's spokesman Gerrit Pretorius told the Reuters news agency that Botha and 22 South African negotiators, including defence minister [[Magnus Malan]] and foreign affairs director Neil van Heerden, had been booked on [[Pan Am Flight 103]]. He said the flight from Johannesburg arrived early in London after a Frankfurt stopover was cut out and the embassy got us on to an earlier flight. | ||

| + | :"Had we been on [[Pan Am Flight 103]] the impact on South Africa and the region would have been massive. It happened on the eve of the signing of the tripartite agreements," said Pretorius, referring to pacts signed at UN headquarters on 22 December 1988 which ended South African and Cuban involvement in Angola, and which led to Namibian independence.<ref>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:REUTERS12NOV94.jpg "Reuters news agency report of 12 November 1994"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pik Botha's claim to have been booked on the [[Pan Am Flight 103|Lockerbie flight]] was shown to be false by the now retired South African MP Colin Eglin of the Democratic Party. In a letter to a British Lockerbie victim’s family dated 18 July 1996, Mr Eglin wrote of questions he had put to South African Justice Minister Dullah Omar in the National Assembly. On 5 June 1996, Mr Eglin asked Mr Omar if Pik Botha and his entourage 'had any plans to travel on this flight ([[Pan Am Flight 103]]) or had reservations for this flight; if so, why were the plans changed?' | ||

| + | |||

| + | In reply in the National Assembly on 12 June 1996, Justice Minister Omar stated he had been informed by the former minister of foreign affairs (Pik Botha) that shortly before finalising their booking arrangements for travel from Heathrow to New York, they learned of an earlier flight from London to New York: namely, Pan Am Flight 101. They consequently were booked and travelled on this flight to New York. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mr Eglin went on to write in his letter to the Lockerbie victim’s family: | ||

| + | :"Since then I have done some more informal prodding. This has led me to the person who made the reservations on behalf of the South African foreign minister Pik Botha and his entourage. This person assures me that he and no-one else was responsible for the reservations, and the reservation made in South Africa for the South African group was originally made on Pan Am 101, departing London at 11:00 on 21 December 1988. It was never made on [[Pan Am 103]] and consequently was never changed. He made the reservation on PA 101 because it was the most convenient flight connecting with South African Airways Flight SA 234 arriving at Heathrow at 07:20 on 21 December 1988." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mr Eglin gave the victim’s family the assurance that he had 'every reason to trust the person referred to' since he had been given a copy of 'rough working notes and extracts from his personal diary of those days.' In his letter Mr Eglin wrote: | ||

| + | :"In the circumstances, I have to accept that an assertion that the reservations of the South African group were either made or changed as a result of warnings that might have been received, is not correct."<ref>[http://lockerbiedivide.blogspot.com/2010/02/south-africans-theory.html?showComment=1267029711774#c7006827410189326148 "Pik Botha and party were booked and travelled on Pan Am Flight 101"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The June 1996 reply by Justice Minister Dullah Omar directly contradicts the ''Reuters'' report of 12 November 1994, which stated: | ||

| + | :"Former South African foreign minister Pik Botha denied on Saturday he had been aware in advance of a bomb on board [[Pan Am Flight 103]] which exploded over Lockerbie in Scotland in 1988 killing 270 people. The minister confirmed through his spokesman that he and his party had been booked on the ill-fated airliner but switched flights after arriving early in London from Johannesburg." | ||

| + | |||

| + | It also conflicts with statements made by Oswald LeWinter and [[Tiny Rowland]] in [[Allan Francovich]]'s 1994 film '[[The Maltese Double Cross]]', which quotes [[Tiny Rowland]] as disclosing that Pik Botha told him that he and 22 South African delegates were going to New York for the Namibian Independence Ratification Ceremony and were all booked on the [[Pan Am Flight 103]]. They were given "a warning from a source which could not be ignored" and changed flights.<ref>[http://lockerbiedivide.blogspot.com/2010/02/south-africans-theory.html?showComment=1267030438405#c4348617946172297375 "A warning from a source which could not be ignored"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==National unity== | ||

Pik Botha subsequently served as Minister of Mineral and Energy Affairs in South Africa's first post-apartheid government from 1994 to 1996 under President [[Nelson Mandela]]. | Pik Botha subsequently served as Minister of Mineral and Energy Affairs in South Africa's first post-apartheid government from 1994 to 1996 under President [[Nelson Mandela]]. | ||

| − | Botha became deputy leader of the National Party in the Transvaal from 1987 to 1996. He retired from politics in 1996 when F | + | Botha became deputy leader of the National Party in the Transvaal from 1987 to 1996. He retired from politics in 1996 when F W de Klerk withdrew the National Party from the government of national unity. |

In 2000, Botha declared his support for President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, and joined the African National Congress. Though he remains an ANC member, Botha has more recently expressed criticism for the government's affirmative action policies saying that the then South African government would never have reached a constitutional settlement with the ANC in 1994 had it insisted on its current affirmative action programme.<ref>Mathabo Le Roux, "'The ANC fooled us' Pik", ''Business Day'', 14 July 2007</ref> | In 2000, Botha declared his support for President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, and joined the African National Congress. Though he remains an ANC member, Botha has more recently expressed criticism for the government's affirmative action policies saying that the then South African government would never have reached a constitutional settlement with the ANC in 1994 had it insisted on its current affirmative action programme.<ref>Mathabo Le Roux, "'The ANC fooled us' Pik", ''Business Day'', 14 July 2007</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | * [[Lockerbie Official Narrative]] | ||

| + | * [[Cameron's Report on Lockerbie Forensic Evidence]] | ||

| + | * [[Document:The Framing of al-Megrahi#The Framing of al-Megrahi|The Framing of al-Megrahi]] | ||

| + | * [[The How, Why and Who of Pan Am Flight 103]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 15:01, 30 October 2013

Roelof Frederik "Pik" Botha (born 27 April 1932, in Rustenburg, Transvaal, Union of South Africa) is a South African diplomat and politician from who served as the country's foreign minister in the last years of the apartheid era.

Pik Botha is not related to the late contemporary National Party politician and State President P W Botha, under whom he served as South Africa's foreign minister.

In Allan Francovich's 1994 film The Maltese Double Cross - Lockerbie, Pik Botha was erroneously reported to have been booked on Pan Am Flight 103 (which was sabotaged over Lockerbie on 21 December 1988) but had been warned against taking that flight.

In fact, Botha and a 22-strong South African delegation had been never been booked on the fatal flight but had travelled on the earlier flight Pan Am 101.[1]

Botha was nicknamed 'Pik' (short for 'pikkewyn', Afrikaans for 'penguin') due to a perceived likeness to a penguin in his stance. This was accentuated when he wore a suit.[2]

Pik Botha is the father of the rock musician Piet Botha. His grandson is Roelof Botha, former CFO of PayPal.

Contents

Diplomat and lawyer

Pik Botha began his career in the South African foreign service in 1953, serving in Sweden and West Germany. From 1963 to 1966, he served on the team representing South Africa at the International Court of Justice in The Hague in the matter of Ethiopia and Liberia v. South Africa, over the South African occupation of South-West Africa (Namibia).

In 1966, Botha was appointed law adviser at the South African Department of Foreign Affairs. In that capacity, he served on the delegation representing South Africa at the United Nations from 1966 to 1974. At this time, he was appointed South Africa's ambassador to the United Nations, but a month after he presented his credentials, South Africa was suspended from membership of the General Assembly. It remained a member of the UN, however, retained a legation throughout these years. Consequently, its flag continued to be flown every day until succeeded by the new flag in 1994, as a reflection of its continued membership of the organisation, if not of the General Assembly.

Politician

In 1970, Botha was elected to the House of Assembly as MP for Wonderboom in the Transvaal, leaving it in 1974. In 1975, Botha was appointed South Africa's Ambassador to the United States, in addition to his UN post. In 1977, he re-entered Parliament as MP for Westdene, and was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs by premier B. J. Vorster.

Botha entered the contest to be leader of the National Party and Prime Minister of South Africa in 1978. He was allegedly considered Vorster's favorite and received superior public support among whites (We want Pik!) but withdrew after criticism concerning his young age, lack of experience (having spent 16 months as foreign minister) and alleged liberal beliefs as opposed to the ultra-conservative NP machinery (in which he lacked a significant position), instead giving support for P. W. Botha, who was ultimately elected.[3]

In 1985, Pik Botha drafted a speech that would have announced the release of Nelson Mandela, but this draft was rejected by P W Botha. The next year, he stated publicly (during a press conference in Parliament, asked by German journalist Thomas Knemeyer) that it would be possible for South Africa to be ruled by a black president provided that there were guarantees for minority rights. President P W Botha quickly forced foreign minister Botha to acknowledge that this position did not reflect government policy.

On 19 October 1986, Pik Botha was one of the first people on the scene of the aircrash in South Africa in which Mozambican President Samora Machel was killed.

In December 1988, Pik Botha flew to Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, with Defence Minister Magnus Malan, and signed a peace protocol with Denis Sassou-Nguesso, President of the Republic of the Congo, and with Angolan and Cuban signatories. At the signing he said:

- "A new era has begun in South Africa. My government is removing racial discrimination. We want to be accepted by our African brothers."

Namibian independence

On 21 December 1988, Pik Botha and a party of negotiators travelled by Pan Am Flight 101 from London to New York for the signing of the Namibia Independence Agreement on 22 December 1988. (Direct flights to the United States by South African Airways had been banned by the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act since 1986.)

On 22 December 1988, Pik Botha signed the New York Accords involving Angola, Cuba and South Africa at United Nations headquarters in New York City, which led to the implementation of Security Council Resolution 435, and to South Africa's relinquishing control of Namibia after decades of illegal occupation.

Lockerbie flight booking subterfuge

Six years after the Lockerbie bombing, apartheid South Africa's foreign minister Pik Botha falsely claimed that he and a negotiating team had originally been booked on the evening Pan Am Flight 103 which crashed at Lockerbie on 21 December 1988, but had changed the booking at the last moment. In fact, the South African booking had always been on the morning Pan Am Flight 101 that departed London Heathrow at 11:00am and arrived safely at New York's JFK airport in the afternoon.

Why the subterfuge, Mr Botha? Was it to divert attention from the highest profile victim on Pan Am Flight 103: Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations and UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson?[4] Upon signature of the Namibia Independence Agreement at UN headquarters on 22 December 1988, Pik Botha would have shaken hands with Mr Carlsson and acknowledged the UN's authority over Namibia. Because Bernt Carlsson was killed at Lockerbie, Mr Botha shook hands instead with the South African appointee Administrator-General of Namibia, Louis Pienaar.

On 12 November 1994, Pik Botha's spokesman Gerrit Pretorius told the Reuters news agency that Botha and 22 South African negotiators, including defence minister Magnus Malan and foreign affairs director Neil van Heerden, had been booked on Pan Am Flight 103. He said the flight from Johannesburg arrived early in London after a Frankfurt stopover was cut out and the embassy got us on to an earlier flight.

- "Had we been on Pan Am Flight 103 the impact on South Africa and the region would have been massive. It happened on the eve of the signing of the tripartite agreements," said Pretorius, referring to pacts signed at UN headquarters on 22 December 1988 which ended South African and Cuban involvement in Angola, and which led to Namibian independence.[5]

Pik Botha's claim to have been booked on the Lockerbie flight was shown to be false by the now retired South African MP Colin Eglin of the Democratic Party. In a letter to a British Lockerbie victim’s family dated 18 July 1996, Mr Eglin wrote of questions he had put to South African Justice Minister Dullah Omar in the National Assembly. On 5 June 1996, Mr Eglin asked Mr Omar if Pik Botha and his entourage 'had any plans to travel on this flight (Pan Am Flight 103) or had reservations for this flight; if so, why were the plans changed?'

In reply in the National Assembly on 12 June 1996, Justice Minister Omar stated he had been informed by the former minister of foreign affairs (Pik Botha) that shortly before finalising their booking arrangements for travel from Heathrow to New York, they learned of an earlier flight from London to New York: namely, Pan Am Flight 101. They consequently were booked and travelled on this flight to New York.

Mr Eglin went on to write in his letter to the Lockerbie victim’s family:

- "Since then I have done some more informal prodding. This has led me to the person who made the reservations on behalf of the South African foreign minister Pik Botha and his entourage. This person assures me that he and no-one else was responsible for the reservations, and the reservation made in South Africa for the South African group was originally made on Pan Am 101, departing London at 11:00 on 21 December 1988. It was never made on Pan Am 103 and consequently was never changed. He made the reservation on PA 101 because it was the most convenient flight connecting with South African Airways Flight SA 234 arriving at Heathrow at 07:20 on 21 December 1988."

Mr Eglin gave the victim’s family the assurance that he had 'every reason to trust the person referred to' since he had been given a copy of 'rough working notes and extracts from his personal diary of those days.' In his letter Mr Eglin wrote:

- "In the circumstances, I have to accept that an assertion that the reservations of the South African group were either made or changed as a result of warnings that might have been received, is not correct."[6]

The June 1996 reply by Justice Minister Dullah Omar directly contradicts the Reuters report of 12 November 1994, which stated:

- "Former South African foreign minister Pik Botha denied on Saturday he had been aware in advance of a bomb on board Pan Am Flight 103 which exploded over Lockerbie in Scotland in 1988 killing 270 people. The minister confirmed through his spokesman that he and his party had been booked on the ill-fated airliner but switched flights after arriving early in London from Johannesburg."

It also conflicts with statements made by Oswald LeWinter and Tiny Rowland in Allan Francovich's 1994 film 'The Maltese Double Cross', which quotes Tiny Rowland as disclosing that Pik Botha told him that he and 22 South African delegates were going to New York for the Namibian Independence Ratification Ceremony and were all booked on the Pan Am Flight 103. They were given "a warning from a source which could not be ignored" and changed flights.[7]

National unity

Pik Botha subsequently served as Minister of Mineral and Energy Affairs in South Africa's first post-apartheid government from 1994 to 1996 under President Nelson Mandela.

Botha became deputy leader of the National Party in the Transvaal from 1987 to 1996. He retired from politics in 1996 when F W de Klerk withdrew the National Party from the government of national unity.

In 2000, Botha declared his support for President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, and joined the African National Congress. Though he remains an ANC member, Botha has more recently expressed criticism for the government's affirmative action policies saying that the then South African government would never have reached a constitutional settlement with the ANC in 1994 had it insisted on its current affirmative action programme.[8]

See also

- Lockerbie Official Narrative

- Cameron's Report on Lockerbie Forensic Evidence

- The Framing of al-Megrahi

- The How, Why and Who of Pan Am Flight 103

References

- ↑ "Why the Lockerbie flight booking subterfuge, Mr Botha?"

- ↑ "Zuid-Afrikaanse oud-minister Pik Botha over de oorlog van 1985 in Namibië: Fidel Castro dacht dat onze kanonnen kernbommen konden afvuren"

- ↑ "We want Pik, we want Pik. . ."

- ↑ "Gordon Brown says Bernt Carlsson was the Lockerbie target"

- ↑ "Reuters news agency report of 12 November 1994"

- ↑ "Pik Botha and party were booked and travelled on Pan Am Flight 101"

- ↑ "A warning from a source which could not be ignored"

- ↑ Mathabo Le Roux, "'The ANC fooled us' Pik", Business Day, 14 July 2007

External links

- Pik Botha on Facebook

- South African History Online

- South African Who's Who

- "From Chequers to Lockerbie: P W Botha's murderous journey"

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here