Sétif and Guelma massacre

| |

| Date | 8 May 1945 - 26 June 1945 |

|---|---|

| Deaths | 6000-30000"-30000" can not be assigned to a declared number type with value 6000. |

| Description | Large French colonial massacre in 1945. |

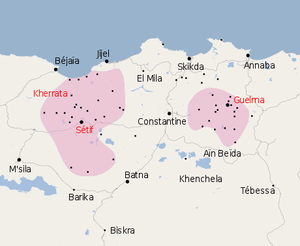

The Sétif and Guelma massacre was a series of attacks by French colonial authorities and pied-noir settler militias on Algerian civilians in 1945 around the market town of Sétif, west of Constantine, in French Algeria. French police fired on demonstrators at a protest on 8 May 1945.[1] Riots in the town were followed by attacks on French settlers (colons) in the surrounding countryside, resulting in 102 deaths. The French colonial authorities and European settlers retaliated by killing between 6,000 and 30,000 Muslims in the region. Both the outbreak and the indiscriminate nature of its retaliation marked a turning point in Franco-Algerian relations, leading to the Algerian War of 1954–1962.[2]

Contents

Background

The anti-colonialist movement started to formalize and get organized before World War II, under the leadership of Messali Hadj and Ferhat Abbas. However, the participation of Algeria in the war had a major impact on the rise of Algerian nationalism. Algiers served as the capital of Free France from 1943, which created hope for many Algerian nationalists. In 1943, Ferhat Abbas published a manifesto[3] that claimed the right of Algerians to have a constitution and a state associated with France. The lack of French reaction lead to the creation of the "Amis du Manifeste et de la Liberté" (AML) and eventually resulted to rise of nationalism. Hundreds of thousands joined to protests in several cities to demand their rights. Contemporary factors other than those of the emergence of Arab nationalism included widespread drought and famine in the Constantine Province,[4] where the European settlers were a minority: in the city of Guelma, there were 4,000 settlers and 16,500 Muslim Algerians. In April 1945, growing racial tensions led to a senior French official proposing the creation of an armed settler militia in Guelma.[5] With the end of World War II in Europe, 4,000 protesters took to the streets of Sétif, a town in northern Algeria, to press new demands for independence on the French administration.[6]

Events

Initial demonstration and killings

The initial outbreak occurred on the morning of 8 May 1945, the same day that Nazi Germany surrendered in World War II. About 5,000 Muslims paraded in Sétif to celebrate the victory. This ended in clashes between the marchers and the local French gendarmerie, when the latter tried to seize banners attacking colonial rule.[7] There is uncertainty over who fired first but both protesters and police were shot. A smaller and peaceful protest of Algerian People's Party activists in the neighboring town of Guelma was violently repressed by the colonial police the same evening. News from Sétif acted as a match on the poor and nationalist rural population, and led to attacks on pieds-noirs in the Sétif countryside (Kherrata, Chevreul) that resulted in the deaths of 102 European colonial settlers (12 in Guelma), plus another hundred wounded.[8]

French repression in Sétif

After five days of chaos, the French colonial military and police suppressed the rebellion, and then, on instructions from Paris,[9] carried out a series of reprisals against Muslim civilians for the attacks on French colonial settlers. The army, which included Foreign Legion, Moroccan and Senegalese troops, carried out summary executions in the course of a ratissage ("raking-over") of Muslim rural communities suspected of involvement. Less accessible mechtas (Muslim villages) were bombed by French aircraft, and the cruiser Duguay-Trouin, standing off the coast in the Gulf of Bougie, shelled Kherrata.[10] Pied-noir vigilantes lynched prisoners taken from local jails or randomly shot Muslims not wearing white arm bands (as instructed by the army) out of hand. It is certain that the great majority of the Muslim victims had not been implicated in the original outbreak.[11]

The US military in Algeria had a part ′The French troops were aided by American forces, who helped 'evacuate' Europeans from sensitive sites before allowing French forces a free rein.'[12]

French repression in Guelma

French repression in the Guelma region differed from that in Sétif in that while only 12 pied-noirs had been killed in the countryside, attacks on civilians lasted until 26 June. The Constantine préfet, Lestrade-Carbonnel had supported the creation of European settler militias, while the Guelma sous-préfet, André Achiari, created an informal justice system (Comité de Salut Public) designed to encourage the violence of the settler vigilantism against unarmed civilians, and to facilitate the identification and murder of nationalist activists.[13] He also instructed police and army intelligence agencies to assist the settler militias. Muslim victims killed in both urban and rural areas were buried in mass graves in places like Kef-el-Boumba, but the corpses were later dug up and burned in Héliopolis.[14]

Victims

These attacks were initially reported to have killed between 1,020 (the official French figure given in the Tubert Report shortly after the massacre) and 45,000 Algerian Muslims (as claimed by Radio Cairo at the time).[15][16] Horne notes that 6,000 was the figure finally settled on by "moderate historians", while Jean-Pierre Peyroulou, crossing Allies' statistics and Marcel Reggui's testimony concludes that a range from 15,000 to 20,000 is likely, contesting Jean-Louis Planche's 20,000 to 30,000 deaths estimation.[17]

The identity of the Muslim Algerian victims differed in Sétif and Guelma. In the countryside outside Sétif, some victims were actual nationalists who had taken part in the insurrection but the majority were uninvolved civilians who had only lived in the same area. However, in Guelma nationalist activists were specifically targeted by French settler vigilantes. Most were male (13% of the men in Guelma were killed),[18] either members of the AML, the Muslim scouts or the local CGT.

Following the military repression the French administration arrested 4,560 Muslims of whom 99 were executed.[19]

Legacy

The Sétif outbreak and the repression that followed marked a turning point in the relations between France and the Muslim population under its control since 1830, when France had colonized Algeria. While the details of the Sétif killings were largely overlooked in metropolitan France, the impact on the Algerian Muslim population was traumatic, especially on the large numbers of Muslim soldiers in the French Army who were then returning from the war in Europe.[20] Nine years later, a general uprising began in Algeria, leading to independence from France in March 1962 with the signing of the Évian Accords.[21]

From 1954 to 1988, the massacres of Sétif and Guelma were commemorated in Algeria, but it was considered as a minor event compared to November 1, 1954, the beginning of the Algerian war for independence, which legitimized the one-party regime. The members of the FLN, as rebels and as State members did not want to emphasize the importance of May 1945: it would have involved remembering that there were other contradictory currents of nationalism,[22] such as Messali Hadj's Algerian National Movement that opposed the FLN. With the democratization movement of 1988, Algerians "rediscovered" a History different from the one told by the regime, as the regime itself was questioned. Research about the massacres of May 1945 was conducted, as well as a memorial will to remember these events. The presidency of Liamine Zéroual and Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and also the Fondation du 8 Mai 1945 also started using the memories of the massacres as a political tool to discuss the consequences of the "colonial genocide"[23] with France.

Comments

In his Mémoires de guerre, Charles de Gaulle, head of the French government at the time of the events, wrote in general:

“In Algeria, the beginning of an insurrection that took place in Constantinois and synchronized with the Syrian riots in May was suppressed by Governor General Chataigneau. "

Houari Boumédiène, the future Algerian president, who saw these events in his youth, writes:

“That day, I aged prematurely. The teenager that I was has become a man. That day the world changed. Even the ancestors moved underground. And the children understood that it would be necessary to fight with weapons in hand to become free men. No one can forget that day."

Kateb Yacine, Algerian writer, then a high school student in Sétif, writes:

"It was in 1945 that my humanitarianism first encountered the most atrocious spectacle. I was twenty. The shock I felt at the ruthless butchery that caused the death of several thousand Muslims, I have never forgotten. This is where my nationalism was cemented."

Impact on modern Algerian–French relations

In February 2005, Hubert Colin de Verdière, France's ambassador to Algeria, formally apologized for the massacre, calling it an "inexcusable tragedy",[24] in what was described as "the most explicit comments by the French state on the massacre".[25]

In 2017, French presidential candidate, Emmanuel Macron considered colonialism as "a crime against humanity".[26] On 8 May 2020, Algerian President, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, decided to commemorate the day at the 75th anniversary of the massacre.[27]

References

- ↑ http://www.algerie-dz.com/article611.html

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/mybattleofalgier00morg/page/17

- ↑ https://texturesdutemps.hypotheses.org/1458

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/insideafrica0000gunt/page/121 121

- ↑ https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/le-cas-de-sa-tif-kherrata-guelma-mai-1945

- ↑ Planche, Jean Louis. Sétif 1945, histoire d'un massacre annoncé. p. 137.

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/mybattleofalgier00morg/page/26

- ↑ Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. New York: The Viking Press. p. 26.

- ↑ General R. Hure, page 449 "L' Armee d' Afrique 1830-1962", Charles-Lavauzelle, Paris-Limoges 1977

- ↑ https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/le-cas-de-sa-tif-kherrata-guelma-mai-1945

- ↑ Horne, p. 27.

- ↑ The French Intifida: The Long War between France and Its Arabs' by Andrew Hussey, pgs. 152-156, pub. 2014

- ↑ Peyroulou, Jean-Pierre (2009). "6. La mise en place d'un ordre subversif, le 9 mai 1945". Guelma, 1945 : une subversion française dans l'Algérie coloniale. Paris: Éditions La Découverte.

- ↑ Peyroulou, Jean-Pierre (2009). "8. La légitimation et l'essor de la subversion 13-19 mai 1945". Guelma, 1945 : une subversion française dans l'Algérie coloniale. Paris: Éditions La Découverte.

- ↑ Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. New York: The Viking Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Bouaricha, Nadjia (7 May 2015). "70 ans de déni". El Watan.

- ↑ https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/le-cas-de-sa-tif-kherrata-guelma-mai-1945

- ↑ Peyroulou, Jean-Pierre (2009). "11. Les morts". Guelma, 1945 : une subversion française dans l'Algérie coloniale. Paris: Éditions La Découverte

- ↑ Rogerson, Barnaby. North Africa. A History From the Mediterranean Shore to the Sahara. p. 297.

- ↑ Porch, Douglas. The French Foreign Legion. p. 569.

- ↑ Edgar O'Ballance, pages 39 and 195 "The Algerian Insurrection 1954-62", Faber and Faber London

- ↑ Peyroulou, Jean-Pierre (2014-12-18). "Les métamorphoses du martyrologe algérien du 8 mai 1945". In Branche, Raphaëlle; Picaudou, Nadine; Vermeren, Pierre (eds.). Autour des morts de guerre : Maghreb - Moyen-Orient. Internationale. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne. pp. 97–118

- ↑ {http://www.elwatan.com/2005-05-08/2005-05-08-18760

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20050511184920/http://voanews.com/english/2005-05-09-voa29.cfm

- ↑ http://www.aljazeera.com/archive/2005/05/200841013384337401.html

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45513842

- ↑ https://www.algerie360.com/massacres-du-8-mai-1945-le-message-cinglant-de-tebboune-a-la-france/