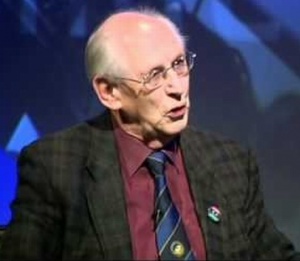

John Mosey

| |

| Known for | Father of a victim of the Lockerbie air disaster |

| Member of | Justice for Megrahi |

Reverend John Mosey is the father of Helga who was one of the 270 victims of the Lockerbie air disaster of 21 December 1988.

In September 2001, John Mosey, a leading member of the Lockerbie support group, UK Families Flight 103, wrote to prime minister Tony Blair to express support for action in Iraq, but also of his concerns. The group reminded Mr Blair of the 1988 tragedy, in which 270 people were killed, and said care should be taken so that more innocent people are not hurt. Mr Mosey's daughter Helga, 19, was among the victims when Pan Am Flight 103 was blown up over Lockerbie:

- "The utmost care must be taken that whatever path is eventually pursued is successful and does not harm innocent people thus producing another batch of terrorists," Mr Mosey wrote. He said the civilised world clearly had to support the US in taking "drastic and effective action to root out this network of evil."

But Rev. Mosey added: "We must find a better way of dealing with our international differences than simply picking up a bigger stick with which to beat the other guys."

On 21 December 2013, Rev. Mosey made the most marvellous Address to the 25th Anniversary of the Pan Am Flight 103 Remembrance Service at Westminster Abbey.

Sadness

Rev. Mosey said his daughter and those who died in Lockerbie were victims of aggressive American foreign policies either in the Gulf or Tripoli. He also expressed the sadness felt by the Lockerbie support group over the US terror attacks and for the victims' families. The utmost care must be taken that whatever path is eventually pursued is successful and does not harm innocent people thus producing another batch of terrorists

- "Our feelings go out to the many in whose homes there is an empty place today, who are eagerly watching their TV screens and waiting desperately for information regarding someone who is missing."

Mr Mosey said he wrote "as an individual whose family has been a victim of a terrorist attack."

Tuesday's attacks in the US brought back memories of 13 years ago to the families of victims and residents of Lockerbie. Pamela Dix, whose brother Peter died in the Lockerbie bomb, said: "It's times like this that those of us who have experienced something of this nature are drawn together."[1]

His daughter's grave

It is a poignant scene. On a Scottish hillside John Mosey kneels at his daughter's modest grave. Using a small penknife he trims the grass that has grown over the edges and lays down a bunch of pink and white freesias. "She loved freesias," he says, before offering a silent prayer.

The letters on the small, gravestone state simply: Alive in Christ. Helga Mosey. 21st September 1969 – 21st December 1988. Pan Am Flight 103. Death where is your victory?

The words reveal the family's deep Christian faith – Mr Mosey is a Pentecostal minister – but also Helga's tender age. She was just 19 when the Pan Am 747 was blown up over Lockerbie by a terrorist bomb, killing a total of 270 people from 21 countries.

Helga, a talented singer and musician who had sung in the national youth choir, was on her way back to New Jersey, America where she was enjoying gap year work as a nanny and looking forward to taking up a place to read music at Lancaster University.

It is nearly 21 years since Helga died. Time and the family's faith have eased their pain but they know it will never go away. "People ask if we've got over Helga's death," Mr Mosey says. "But you don't get over it. It's not like an illness you recover from. It's an amputation that you have to live with."

His daughter's grave is at Tundergarth church near Lockerbie, 500 yards from where her body was found. Mr Mosey gazes out from the graveyard across rolling fields where sheep and horses graze indolently, an idyllic scene at odds with the grief of a man on a pilgrimage he and his German-born wife Lisa, a former nurse, make at least once a year from their home in Cumbria.

- "We cried every day for weeks after Helga died," he says. "As a church minister I was used to talking about death and consoling the bereaved but when it happens to you it's completely different. It knocks you for six.

- "I took Helga to Heathrow that day," he says, "As I kissed her goodbye I could smell the apple shampoo she had used. I will never forget that smell."

For years after her death Mr Mosey's sleep was disturbed by dreams in which he was desperately trying to get to Heathrow to tell the airline to ground Flight 103 because there was a bomb on board.

After the crash a "property store" was set up in Lockerbie where families could collect the victims' clothes and other belongings that had been gathered from an area stretching for up to 40 miles from the crash site.

The Moseys found one of Helga's sweatshirts which her mother wears to this day. They also found her bracelets and white wristwatch.

Mr Mosey, who says he still sometimes talks to Helga as if she were alive, put the watch on the desk in her bedroom at the Victorian semi in Birmingham where they lived at the time.

- "It worked for another two years," he says. "The watch survived the bomb but our daughter didn't."

His wife says the pain of loss was "almost physical" for a long time after Helga died and still comes back at unexpected moments.

- "It can be the mention of a place, something somebody says or a piece of music," she says.

The one that never fails to provoke tears is the sound of Bist Du Bei Mir (If you are with me) an aria by the German composer Stölzel, often attributed to Bach, which Helga's former music teacher sang at her memorial service.

- "Helga adored that song and it knocks me over every time I hear it," she says. "I miss not having my daughter but she is still part of our lives, part of our family. She would have been 40 this year and we will never know what she might have become. But it is strange that to us she will always be 19 while we are all growing older."

Mrs Mosey's efforts to cope with her grief were helped by the fact that she had "a son and husband and an aunt to look after," she says. "It was good to be kept busy. I had to get on with it. I had to be there for the living."

She says that they had "eight horrible years" after Helga's death. "A lot of other things happened and it was an awful time," she says.

Her husband found other leaders at his church were unable to cope with his loss and grief and his relationship with at least one senior figure deteriorated to the point where Mr Mosey had a breakdown, left the church and was taking antidepressants.

Doctors thought he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and he did not work for 18 months.

But he fought back, helped by his "stalwart" wife and their Christian beliefs. "Our faith gave us strength," he says. "That is what has got us through the dark days. We don't understand why our child was taken from us at the age of 19 but we trust in God."

Helga's death was also deeply traumatic for Marcus, her younger brother, then 15. He was unable to talk about it for three years but he too has pulled through and is now a church minister, married with two young children.

The Moseys were determined not to lapse into self-pity nor to feel bitter or angry towards whoever killed Helga. They forgave the killers almost immediately and turned to the Bible for guidance, taking as their motto a sentence from Paul's Letter to the Romans, chapter 12 verse 21: "Don't be overcome by evil, but overcome evil by doing good."

They set about putting this creed into practice with gusto. They set up the Helga Mosey Memorial Trust to provide care and education for needy children in developing countries and threw themselves into charity work.

Mr Mosey has given hundreds of talks and seminars on grief, forgiveness and Christianity in churches all over the world. He spent 16 years, until two years ago, working for 'Disaster Action', helping victims' relatives and working with police, social services and others involved in the aftermath of disasters including the Kings Cross fire, the sinking of the Herald of Free Enterprise ferry and the Piper Alpha fire.

A few years ago the family received $10 million (worth £5.7 million at the time) in compensation from the Libyan government. Even after paying lawyers around $3 million, they were financially secure for life. But although they live comfortably they chose not to spend the money on a lavish lifestyle but on good works.

The couple opened homes in India and the Philippines for abandoned and abused children which local leaders say have saved many young lives.

This, they feel, is Helga's legacy. "In death Helga has touched thousands of people that she would not have done if she were still alive," says Mrs Mosey. "That doesn't mean I wouldn't rather have her with us today but it does mean that some good can come out of bad things."

Her husband says: "When my wife and I visit the homes and see those healthy and loved kids, knowing that many of them would be dead today if Helga was alive, we feel that we have got something back... What better way of striking back at evil can there be than to bless some of its saddest victims?"

Perhaps most surprisingly of all, the Moseys have made a considerable donation to a charity in Libya where they have paid for an ambulance for handicapped children. The link with Libya was forged when Mr Mosey got to know a senior Libyan diplomat during the trial of Abdelbaset Megrahi, the Libyan intelligence agent convicted of the Lockerbie bombing.

- "It might sound strange to give money to a country involved in the death of our daughter," Mr Mosey says. "But we want to build bridges. We want good to overcome evil." He went to Libya twice at the invitation of the Tripoli government and chose the charity that he wanted to help.

Mr Mosey says the loss of their daughter has divided their lives into two. "It is a huge watershed," Mr Mosey says. "We refer to everything as 'before Lockerbie' or 'after Lockerbie'. It took our lives in a totally new direction."

Back in the small, ordinary town that is Lockerbie, Mr Mosey marvels at how the "crater" left by the Pan Am jet's wings and fuselage has been transformed into a memorial garden. The houses that were destroyed have been rebuilt.

The residents in this area, like many in Lockerbie, talk reluctantly about what happened over two decades ago. "It was like nothing you could have imagined," said one woman in her seventies who lost three friends when the blown-up plane came down. :"But it was a long time ago. The town wants to move on. We don't want to wallow in the past." Angela Garva, 48, a florist in the town, survived the disaster because she was not needed by the hotel she worked for and so did not wait for her lift at the usual place – where one of the Pan Am jet's engines came down.

- "We can never forget and we should never forget but we can't dwell on it," she says. "It put Lockerbie on the map for the wrong reasons, though it has helped my business because so many people want to put flowers on the graves."

The Moseys know that they cannot "move on" from the terrorist attack that took their daughter's life until they know the truth about who killed her.

Megrahi's decision to drop his appeal denied them the chance to hear new evidence in court that might have given clues about the killers. They, and the other Lockerbie families, will continue to fight for an independent public inquiry.

- "I don't know if we will ever get the truth about what happened," Mr Mosey says. "But we will never give up trying. We owe it to Helga."[2]

25th Anniversary of Lockerbie

On 21 December 2013, Rev. John Mosey made the following Address to the 25th Anniversary Service of Remembrance at Westminster Abbey:

- We have gathered here with the specific purpose of remembering those who we have lost. But as we remember them there is always another "remembering" lurking not far away: the remembering of the way in which they were snatched mercilessly from us. It is what we do with this remembering that I want to think about for a few minutes. I go back to my final words in this place at the tenth anniversary.

- "Five days after ‘Lockerbie’, I sat in my daughter’s bedroom. I suppose that I was looking for a foundation on which to build my strategy for dealing with this deep wound I had received. I was drawn to the words which the Apostle Paul wrote to the Christians in Rome suffering under the Emperor Nero, ‘Don’t be overcome by evil, but overcome evil by doing good’."

- I was born in Coventry as the Nazi bombs were raining down on the city. Whilst studying at the Lanchester College of Art and Technology I often ate my lunchtime sandwiches in the nearby ruins of the old cathedral. Soon after the blitz they had taken two of the charred beams from the rubble and fastened them in the form of a cross on the east wall placing beneath them the words, "Father, forgive". Little did I think then that there would come a time in my life when I was going to have to give a great deal of thought to this subject of "Forgiveness"; what it is and what it is not.

- Whatever our definition of "Forgiveness" it is clear from reading the Bible, and the teachings of Jesus in particular, that forgiveness and reconciliation are a huge part of God’s agenda. The "Sermon on the Mount" is acclaimed widely, even by those of other or no religious persuasions as being one of the very finest codes for living. In it Jesus, directly after giving us the "Lord’s Prayer" containing "Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors", gave it double emphasis and made it a condition for God’s forgiveness. "For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses." For any who call themselves "Christian" un-forgiveness is not an option. George Herbert, the seventeenth-century poet and theologian put it well, "He who cannot forgive breaks the bridge over which he himself must pass."

- In my boyhood I had a friend who went into hospital with appendicitis. After the operation he came home but a few days later had to return to the hospital with an infection in the wound. He died shortly afterwards, not of the appendicitis but because of the secondary infection. The damage we inflict on ourselves by harbouring anger and bitterness can be far more serious than the initial wound.

- How we deal with this second "remembering" is crucial. I have seen lives destroyed, not by the cruel events of life, but by the anger and bitterness (often justified) that they have allowed and even encouraged to fill their thoughts. I return to St Paul’s words, "Don’t be overcome by evil, but overcome evil by doing good". Our anger and bitterness only hurt us. The objects of our anger, if they are aware of it, usually couldn’t care less: it even adds interest to their investment.

- The recently departed president Nelson Mandela once said, "As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn't leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I'd still be in prison."

- Forgiveness does not mean we are soft on crime. If you beat me up outside and steal my wallet I will forgive you - but I won’t stop the policeman from arresting you. Forgiveness is a very personal thing but the Bible clearly teaches that the law is God’s protection for society. The law, civic or international (such as it is) must, within the limits of its remit, pursue and prosecute but if it becomes vengeful or vindictive it is out of order.

- Our people were murdered in revenge for an act of Western aggression which was, in turn, an act of revenge. It is by doing something to try to break the vicious circle of hatred and aggression that we become winners.

- On that fifth morning after her murder I sat in our daughter’s room remembering the previous evening’s news that it was a bomb that had destroyed Pan Am 103. I recalled the cries for revenge and thought, "If I want someone dead because my child is dead I become no better than the terrorists: I bring myself right down to their level."

- The words of Gandhi came to mind. "‘An eye for an eye’, and the world will soon be blind." We could not have a better example than that of Nelson Mandela’s apparent total lack of vengefulness and his reaching out for reconciliation.

- We remember those we lost with love, sorrow and pain but it is what we do with this other "remembering" that can affect, not only our personal lives but the wider world we live in.

- So, "we will remember them" and remember those who did this dreadful deed and those who have assiduously sought to hide the truth from us. We have witnessed the death of honour, truth and justice and so the death of trust. Evil and injustice must be bravely confronted and every effort made to expose the truth but we must pursue our quest without malice or desire for revenge.

- The Christmas message of the Gospel, symbolised by the incarnation and the cross, is reconciliation. "God was in Christ, reconciling the world to himself." Let us seek, at least on a personal level, to break the never ending cycle of aggression. "Don’t be overcome by evil, but overcome evil by doing good."[3]

References

- ↑ "Lockerbie father calls for restraint"

- ↑ "Lockerbie victim's father: 'I feel like I've lost a limb'"

- ↑ "SERMON GIVEN AT A SERVICE OF REMEMBRANCE TO MARK THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE LOCKERBIE AIR DISASTER" 21st December 2013 at 6:45 pm The Reverend John Mosey, UK Families Flight 103