Difference between revisions of "Eugene de Kock"

(Inaugurating) |

(Expanding) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

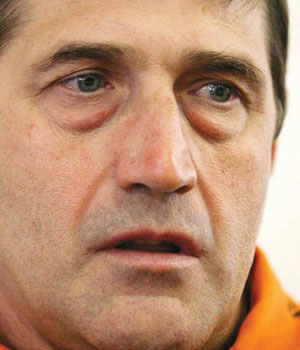

| − | [[File:Eugene_De_Kock.jpg|300px|right|thumb|[[Eugene de Kock]] South African apartheid-era killer | + | [[File:Eugene_De_Kock.jpg|300px|right|thumb|[[Eugene de Kock]] South African apartheid-era killer dubbed 'Prime Evil' by the media]] |

'''Eugene de Kock''' the son of a magistrate, was born in George in the Western Cape on 29 January 1949. He joined the South African Police, and in the late 1970s was deployed to Rhodesia where a bloody bush war was being waged at the time. He later joined the notorious [[Koevoet]] paramilitary unit in the then [[Namibia|South-West Africa]]. | '''Eugene de Kock''' the son of a magistrate, was born in George in the Western Cape on 29 January 1949. He joined the South African Police, and in the late 1970s was deployed to Rhodesia where a bloody bush war was being waged at the time. He later joined the notorious [[Koevoet]] paramilitary unit in the then [[Namibia|South-West Africa]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dubbed "Prime Evil" by the media, De Kock has spent over two decades behind bars, following his arrest in 1994 and his conviction two years later in the Pretoria High Court. De Kock was sentenced to two terms of life imprisonment for the murders of Japie Kereng Maponya and the so-called Nelspruit five: Oscar Mxolisi Ntshota, Glenack Masilo Mama, Lawrence Jacey Nyelende, Khona Gabela and Tisetso Leballo. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Kock was sentenced to a further 212 years' imprisonment for conspiracy to commit murder, culpable homicide, kidnapping, assault, and fraud. He began serving his sentence at Pretoria's C-Max prison and in 1997 was moved to Pretoria Central prison. In January 2015, De Kock was granted parole by Justice Minister Michael Masutha who said he would be released "in the interests of nation-building".<ref>[http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/SAs-Prime-Evil-to-walk-after-20yrs-20150130 "SA's 'Prime Evil' to walk after 20yrs"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Archbishop Emeritus [[Desmond Tutu]], who chaired the [[TRC]], said the decision to release him represented a milestone on South Africa's road to reconciliation and healing: | ||

| + | :"I pray that those whom he hurt, those from whom he took loved ones, will find the power within them to forgive him. Forgiving is empowering for the forgiver and the forgiven - and for all the people around them. But we can't be glib about it; it's not easy," [[Archbishop Tutu]] said.<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-31054912 "South Africa apartheid assassin De Kock given parole"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Amnesty== | ||

| + | At the [[Truth and Reconciliation Commission]] Eugene de Kock confessed to more than 100 acts of murder, torture and fraud, taking full responsibility for the activities of his undercover unit. He was granted amnesty for most offences but the [[TRC]] only had the power to grant amnesty to human rights violators whose crimes were linked to a political motive and who made a full confession. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the TRC hearings, De Kock described the murders of a number of African National Congress ([[ANC]]) members, in countries including Lesotho, Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Angola, naming the police commander above him in each case. His amnesty application included: | ||

| + | *Commander of Vlakplass police unit from 1983; | ||

| + | *Confessed to hundreds of murders at the [[TRC]]; | ||

| + | *Nicknamed "Prime Evil" for the death-squad revelations; | ||

| + | *Sentenced to 212 years and two life terms in 1996; | ||

| + | *Served 20 years before getting parole.<ref>[http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/south-africas-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-grants-amnesty-apartheid-death-squad-c "South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission grants amnesty to apartheid death squad commander Eugene de Kock"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Forgiving== | ||

| + | Sandra Mama, widow of Glenack Mama who was killed by De Kock in 1992, said she thought the minister was right in granting parole: | ||

| + | :"I think it will actually close a chapter in our history because we've come a long way and I think his release will just once again help with the reconciliation process because there's still a lot of things that we need to do as a country," she told the BBC. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2012, Marcia Khoza publicly forgave him for killing her mother [[ANC]] activist Portia Shabangu. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Reaching out for Olof Palme== | ||

| + | At his criminal trial in September 1996, Eugene de Kock dropped a bombshell by implicating an apartheid-era South African spy in the still-unsolved assassination of Swedish Prime Minister [[Olof Palme]] a decade earlier. De Kock said "Operation Long Reach" a now-defunct South African military intelligence project headed by operative [[Craig Williamson]] had "played a role" in the murder of [[Olof Palme|Palme]], a staunch apartheid foe. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Kock gave no other details, but he said he had already told prosecutors what he knows. Rumours of South African involvement had circulated for years, but De Kock's allegations apparently offered fresh leads: | ||

| + | :"A part of the De Kock information is new," Lars Jonsson, deputy director of the police investigation in Stockholm, told the Swedish news agency TT. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Olof Palme]] was shot once in the back with a .357 magnum pistol while walking home from a Stockholm cinema with his wife on 28 February 1986. The lone assassin was never caught. Swedish detectives never publicly revealed any South African links to the slaying. But Palme had been fiercely critical of apartheid and had fought to impose comprehensive trade and cultural sanctions against the white minority regime in Pretoria. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Craig Williamson|Williamson]] denied involvement in [[Olof Palme|Palme]]'s murder. But he has publicly admitted parts of his life as a covert operative. The former military intelligence major is known in South African headlines as a "super spy" who said he infiltrated and informed on South African anti-apartheid groups in Europe in the 1970s, including the military wing of the then-banned [[African National Congress]]. He returned home in 1980 after his cover was blown and soon was second-in-command of the foreign section of South Africa's security police, responsible for covert operations. De Kock testified last week that [[Craig Williamson|Williamson]] directed the 1982 bombing of the ANC's European headquarters in London. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "Operation Long Reach" was the code name of a covert project, run by [[Craig Williamson|Williamson]], that used a bogus security company to gather intelligence abroad for the military, especially in countries where the apartheid government was not permitted to open an embassy. De Kock's latest allegation came on the sixth day of his testimony for mitigation of sentence. He faced multiple life terms after his conviction for 89 crimes, including six murders, during his years as head of the Vlakplaas death squad, named after a grassy farm west of here that was its base. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Speaking in a monotone, De Kock rocked South Africa with his lurid recollections of official bombings, murder, theft and perjury. The former police colonel admitted to scores, if not hundreds, of chilling crimes in the government's dirty war. And he invariably named more senior officials who he said had given the orders, shared in the spoils or helped hide the horrors: | ||

| + | :"The [police commissioner], the minister, the president all helped to cover up," he said. "Without the system, we could never have escaped the consequences of our deeds." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some key allegations, especially those involving former presidents [[F W de Klerk]] and [[P W Botha]], were based on hearsay. But if the rest was even partly true, De Kock had already exposed far more detail than was ever publicly known about the apartheid state's monstrous security apparatus and those who ran it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jan d'Oliveira, the chief prosecutor, said in an interview that dozens of prosecutions may follow as a result. He said investigators were trying to verify and evaluate De Kock's allegations as quickly as possible. At least one prosecution could begin in several weeks involving "more than 30 murders," he said. D'Oliveira declined to detail the forthcoming cases, explaining: "We have a real fear that if we speak out, witnesses or evidence will disappear." | ||

| + | |||

| + | He said the investigations may be curtailed if those named by De Kock apply for amnesty from the [[Truth and Reconciliation Commission]], which is empowered to pardon those who fully confess apartheid crimes. A [[TRC]] spokesman, John Allen, said no one named by De Kock has applied for amnesty. The Transvaal attorney general also said De Kock's infamous Vlakplaas death squad was not the worst of what now appears a nightmarish web of state-sanctioned murder and dirty tricks units. "It's been my view all along that the De Kock case was the tip of the iceberg," D'Oliveira said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | That is clearly De Kock's view. In previous testimony, he said his team of killers was "way down on the list" of official hit squads: | ||

| + | :"I know about other units that put [us] in the shade," he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He said the Directorate of Covert Collection in military intelligence and the notorious [[Civil Cooperation Bureau]] in the [[South African Defence Force|SADF]] were much larger and had committed far more murder and mayhem. Even earlier groups, such as the infamous "Z Squad" and "K Unit" in the [[BOSS|Bureau of State Security]], had a bloodier record, he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Kock also alleged that cells of four to six agents were trained and deployed "at every security branch in the country" for assassinations. The dreaded security police had offices in every major town. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A woman who visits him regularly in Pretoria Central Prison said De Kock regrets that he has forgotten so much: | ||

| + | :"I think he's trying to clear his conscience," she said. "He says he's got nothing to lose." | ||

| + | |||

| + | But in court, De Kock said he regretted something else: "I cannot describe how contaminated and dirty I feel. Whatever we set out to do . . . we failed to achieve," he said. "All we succeeded in doing was to deliver dead bodies, pain and children who will never know their fathers."<ref>[http://articles.latimes.com/1996-09-27/news/mn-48144_1_apartheid-spy "Apartheid Spy Tied to '86 Assassination of Sweden's Palme"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 22:34, 30 January 2015

Eugene de Kock the son of a magistrate, was born in George in the Western Cape on 29 January 1949. He joined the South African Police, and in the late 1970s was deployed to Rhodesia where a bloody bush war was being waged at the time. He later joined the notorious Koevoet paramilitary unit in the then South-West Africa.

Dubbed "Prime Evil" by the media, De Kock has spent over two decades behind bars, following his arrest in 1994 and his conviction two years later in the Pretoria High Court. De Kock was sentenced to two terms of life imprisonment for the murders of Japie Kereng Maponya and the so-called Nelspruit five: Oscar Mxolisi Ntshota, Glenack Masilo Mama, Lawrence Jacey Nyelende, Khona Gabela and Tisetso Leballo.

De Kock was sentenced to a further 212 years' imprisonment for conspiracy to commit murder, culpable homicide, kidnapping, assault, and fraud. He began serving his sentence at Pretoria's C-Max prison and in 1997 was moved to Pretoria Central prison. In January 2015, De Kock was granted parole by Justice Minister Michael Masutha who said he would be released "in the interests of nation-building".[1]

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, who chaired the TRC, said the decision to release him represented a milestone on South Africa's road to reconciliation and healing:

- "I pray that those whom he hurt, those from whom he took loved ones, will find the power within them to forgive him. Forgiving is empowering for the forgiver and the forgiven - and for all the people around them. But we can't be glib about it; it's not easy," Archbishop Tutu said.[2]

Amnesty

At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Eugene de Kock confessed to more than 100 acts of murder, torture and fraud, taking full responsibility for the activities of his undercover unit. He was granted amnesty for most offences but the TRC only had the power to grant amnesty to human rights violators whose crimes were linked to a political motive and who made a full confession.

During the TRC hearings, De Kock described the murders of a number of African National Congress (ANC) members, in countries including Lesotho, Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Angola, naming the police commander above him in each case. His amnesty application included:

- Commander of Vlakplass police unit from 1983;

- Confessed to hundreds of murders at the TRC;

- Nicknamed "Prime Evil" for the death-squad revelations;

- Sentenced to 212 years and two life terms in 1996;

- Served 20 years before getting parole.[3]

Forgiving

Sandra Mama, widow of Glenack Mama who was killed by De Kock in 1992, said she thought the minister was right in granting parole:

- "I think it will actually close a chapter in our history because we've come a long way and I think his release will just once again help with the reconciliation process because there's still a lot of things that we need to do as a country," she told the BBC.

In 2012, Marcia Khoza publicly forgave him for killing her mother ANC activist Portia Shabangu.

Reaching out for Olof Palme

At his criminal trial in September 1996, Eugene de Kock dropped a bombshell by implicating an apartheid-era South African spy in the still-unsolved assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme a decade earlier. De Kock said "Operation Long Reach" a now-defunct South African military intelligence project headed by operative Craig Williamson had "played a role" in the murder of Palme, a staunch apartheid foe.

De Kock gave no other details, but he said he had already told prosecutors what he knows. Rumours of South African involvement had circulated for years, but De Kock's allegations apparently offered fresh leads:

- "A part of the De Kock information is new," Lars Jonsson, deputy director of the police investigation in Stockholm, told the Swedish news agency TT.

Olof Palme was shot once in the back with a .357 magnum pistol while walking home from a Stockholm cinema with his wife on 28 February 1986. The lone assassin was never caught. Swedish detectives never publicly revealed any South African links to the slaying. But Palme had been fiercely critical of apartheid and had fought to impose comprehensive trade and cultural sanctions against the white minority regime in Pretoria.

Williamson denied involvement in Palme's murder. But he has publicly admitted parts of his life as a covert operative. The former military intelligence major is known in South African headlines as a "super spy" who said he infiltrated and informed on South African anti-apartheid groups in Europe in the 1970s, including the military wing of the then-banned African National Congress. He returned home in 1980 after his cover was blown and soon was second-in-command of the foreign section of South Africa's security police, responsible for covert operations. De Kock testified last week that Williamson directed the 1982 bombing of the ANC's European headquarters in London.

"Operation Long Reach" was the code name of a covert project, run by Williamson, that used a bogus security company to gather intelligence abroad for the military, especially in countries where the apartheid government was not permitted to open an embassy. De Kock's latest allegation came on the sixth day of his testimony for mitigation of sentence. He faced multiple life terms after his conviction for 89 crimes, including six murders, during his years as head of the Vlakplaas death squad, named after a grassy farm west of here that was its base.

Speaking in a monotone, De Kock rocked South Africa with his lurid recollections of official bombings, murder, theft and perjury. The former police colonel admitted to scores, if not hundreds, of chilling crimes in the government's dirty war. And he invariably named more senior officials who he said had given the orders, shared in the spoils or helped hide the horrors:

- "The [police commissioner], the minister, the president all helped to cover up," he said. "Without the system, we could never have escaped the consequences of our deeds."

Some key allegations, especially those involving former presidents F W de Klerk and P W Botha, were based on hearsay. But if the rest was even partly true, De Kock had already exposed far more detail than was ever publicly known about the apartheid state's monstrous security apparatus and those who ran it.

Jan d'Oliveira, the chief prosecutor, said in an interview that dozens of prosecutions may follow as a result. He said investigators were trying to verify and evaluate De Kock's allegations as quickly as possible. At least one prosecution could begin in several weeks involving "more than 30 murders," he said. D'Oliveira declined to detail the forthcoming cases, explaining: "We have a real fear that if we speak out, witnesses or evidence will disappear."

He said the investigations may be curtailed if those named by De Kock apply for amnesty from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which is empowered to pardon those who fully confess apartheid crimes. A TRC spokesman, John Allen, said no one named by De Kock has applied for amnesty. The Transvaal attorney general also said De Kock's infamous Vlakplaas death squad was not the worst of what now appears a nightmarish web of state-sanctioned murder and dirty tricks units. "It's been my view all along that the De Kock case was the tip of the iceberg," D'Oliveira said.

That is clearly De Kock's view. In previous testimony, he said his team of killers was "way down on the list" of official hit squads:

- "I know about other units that put [us] in the shade," he said.

He said the Directorate of Covert Collection in military intelligence and the notorious Civil Cooperation Bureau in the SADF were much larger and had committed far more murder and mayhem. Even earlier groups, such as the infamous "Z Squad" and "K Unit" in the Bureau of State Security, had a bloodier record, he said.

De Kock also alleged that cells of four to six agents were trained and deployed "at every security branch in the country" for assassinations. The dreaded security police had offices in every major town.

A woman who visits him regularly in Pretoria Central Prison said De Kock regrets that he has forgotten so much:

- "I think he's trying to clear his conscience," she said. "He says he's got nothing to lose."

But in court, De Kock said he regretted something else: "I cannot describe how contaminated and dirty I feel. Whatever we set out to do . . . we failed to achieve," he said. "All we succeeded in doing was to deliver dead bodies, pain and children who will never know their fathers."[4]