Difference between revisions of "Coventry Four"

(Importing from Wikipedia) |

(Expanding and referencing) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Smuggling activities== | ==Smuggling activities== | ||

| + | The four South Africans plus three Britons were charged in the Coventry Magistrates Court on 2 April 1984 with conspiring to export to South Africa high pressure gas cylinders, radar magnetrons, aircraft parts and other military equipment<ref name="MOSA"/><ref name="UNSC">{{cite web|url=http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/history/aam/abdul-15.html|publisher=African National Congress|date=1984-04-09|title=Statement Before the Security Council Committee Established by Resolution 421 (1977) Concerning the Question of South Africa}}</ref> in violation of the mandatory arms embargo imposed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 418. The uncovering of their smuggling operation and subsequent arrest followed the discovery of a shipment of artillery elevating gears at Birmingham International Airport in 1984. | ||

| − | The | + | The "Coventry Four" were Hendrik Jacobus Botha, Stephanus Johannes de Jager, William Randolph Metelerkamp and Jacobus Le Grange. In the front company, McNay Pty Ltd, they operated on behalf of Kentron. Metelerkamp was the Managing Director, Botha was in charge of administration and security, De Jager was the company accountant, while Le Grange was the technical expert.<ref name="MOSA"/> One of the ways in which they worked around the international arms embargo was for Le Grange to travel to the United States to source military materiel - this would subsequently be imported by Fosse Way Securities in the UK, before being shipped onwards to South Africa via other countries.<ref name="MOSA"/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | One of the ways in which they worked around the international arms embargo was for Le Grange to travel to the United States to source military materiel - this would subsequently be imported by Fosse Way Securities in the UK, before being shipped onwards to South Africa via other countries.<ref name="MOSA"/> | ||

A fifth man, professor Johannes Cloete of Stellenbosch University – a key player in South Africa's missile development program – was arrested at the same time as the Coventry Four. But, according to ''The Guardian'' of 17 December 1988, Cloete's arrest was quickly followed by his release without charge on instructions from senior Whitehall officials. | A fifth man, professor Johannes Cloete of Stellenbosch University – a key player in South Africa's missile development program – was arrested at the same time as the Coventry Four. But, according to ''The Guardian'' of 17 December 1988, Cloete's arrest was quickly followed by his release without charge on instructions from senior Whitehall officials. | ||

| Line 13: | Line 10: | ||

The three British men arrested at the same time were Michael Swann, Derek Salt and Michael Henry Gardiner.<ref name="UNSC"/> Salt had previously been dismissed from another company for manufacturing ammunition dies for the South African military, which he concealed as sewing machine equipment. After his dismissal, Salt continued to deal with Armscor, despite the international arms embargo. His company in Coventry manufactured mortar casings to Armscor's specifications, and also sub-contracted the manufacture of the high-precision artillery gears seized by HM Customs to a German company.<ref name="MOSA">{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=zEQ-Km_KShAC&pg=PA238&dq=Coventry+Four&sig=f48spXJo8chofA0jdDIacKxXLig#PPA238,M1|title=War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa|author=Jacklyn Cock, Laurie Nathan|year=1989|publisher=New Africa Books | isbn=978-0-86486-115-3}}</ref> | The three British men arrested at the same time were Michael Swann, Derek Salt and Michael Henry Gardiner.<ref name="UNSC"/> Salt had previously been dismissed from another company for manufacturing ammunition dies for the South African military, which he concealed as sewing machine equipment. After his dismissal, Salt continued to deal with Armscor, despite the international arms embargo. His company in Coventry manufactured mortar casings to Armscor's specifications, and also sub-contracted the manufacture of the high-precision artillery gears seized by HM Customs to a German company.<ref name="MOSA">{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=zEQ-Km_KShAC&pg=PA238&dq=Coventry+Four&sig=f48spXJo8chofA0jdDIacKxXLig#PPA238,M1|title=War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa|author=Jacklyn Cock, Laurie Nathan|year=1989|publisher=New Africa Books | isbn=978-0-86486-115-3}}</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | ==Remanded in custody== |

| + | The "Coventry Four" were remanded in custody and their passports confiscated. After several weeks, they were released on bail of £200,000 when André Pelser, 1st Secretary at the South African embassy, waived his diplomatic immunity and stood surety. Then, following an alleged intervention from 10 Downing Street, they applied to a Judge sitting in Chambers to recover their passports. In an unusual ruling which allowed accused criminals to leave the jurisdiction, Judge Lennard agreed the men could go home on condition they returned for the next court hearing in June. Bail was doubled to £400,000. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The four turned up in June for another remand, but South Africa then found a reason to avoid a trial. | ||

==Controversial visit== | ==Controversial visit== | ||

| − | + | On 2 June 1984, British prime minister [[Margaret Thatcher]] controversially invited South Africa's president [[P W Botha]] and foreign minister [[Pik Botha]] to a meeting at Chequers in an effort to stave off growing international pressure for the imposition of economic sanctions against South Africa, where both the U.S. and Britain had invested heavily. Although not officially on the meeting's agenda, the "Coventry Four" affair clouded both the proceedings at Chequers and Britain's bilateral diplomatic relations with South Africa.<ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=4337747316094&l=786b251874 "From Chequers to Lockerbie: Botha's murderous journey"]</ref> | |

| − | In August | + | ==Quid pro quo== |

| − | + | In August 1984, when anti-apartheid activists – threatened with arrest in South Africa – took refuge in the British consulate in Durban, Pik Botha decided to retaliate by refusing to allow the "Coventry Four" to return to Britain to stand trial.<ref>''The Guardian'' 13 December 1988 Letters Geoffrey Bindman ''Shabby manoeuvres that aid and abet Botha''</ref> Foreign Office minister, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Rifkind Malcolm Rifkind], reported to the House of Commons that the South African government was wholly to blame for the men's non-appearance in a British court, and that Pretoria should cooperate. In the event the men did not come back to stand trial and no action was taken against South Africa.<ref>''The Guardian'' 17 December 1988</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ==Bail forfeited== |

| − | + | When the case came up again at Coventry magistrates in October, counsel for the South African Government, Mr George Carman QC, said: "They were simply obeying the expressed intention of their own government." Mr Pelser, who remained at the embassy for another two years, agreed to forfeit the bail money. | |

| + | |||

| + | Salt was given a 10-month jail sentence and fined £25,000 for his part in the operation, while the UK companies involved paid fines of £193,000.<ref name="MOSA"/><ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=4335548261119&l=eb70d42a83 "How SA arms team evaded British trial"]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Thatcher critic== | ||

| + | In August 1989, British diplomat [[Patrick Haseldine]] was dismissed for publicly criticising Mrs Thatcher in the press of double standards over the release of the "Coventry Four". | ||

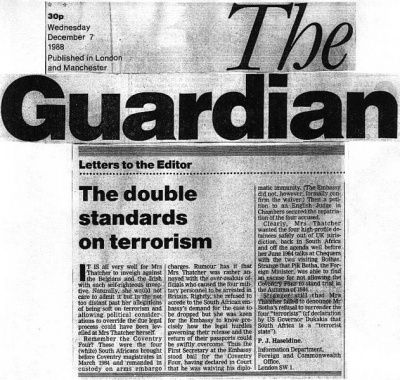

| + | [[Image:PatrickHaseldine3.jpg|right|thumb|400px|''The Guardian'' published [[Patrick Haseldine]]'s letter on 7 December 1988]] | ||

| + | Text of Haseldine's letter:<ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2806455434754&l=400a8947c4 Letter to ''The Guardian'' December 7, 1988]</ref><ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=4284974596809&l=0a154fc767 "Fresh facts support PM's critic"]</ref><ref>[http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=4278461233979&l=1b8b35e497 "Sacked Thatcher critic sues ministry"]</ref><ref>{{cite news|court=European Court of Human Rights|litigants=[[Patrick Haseldine]] vs United Kingdom|date=1992-05-13|url=http://cmiskp.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.aspaction=html&documentId=665945&portal=hbkm&source=externalbydocnumber&table=F69A27FD8FB86142BF01C1166DEA398649}}</ref><blockquote>"It is all very well for Mrs Thatcher to inveigh against the Belgians and the Irish with such self-righteous invective. Naturally, she would not care to admit it but in the not too distant past her allegations of being soft on terrorism and allowing political considerations to override the due legal process could have been levelled at Mrs Thatcher herself. Remember the "Coventry Four"? These were the four (white) South Africans brought before Coventry magistrates in March 1984 and remanded in custody on arms embargo charges. Rumour has it that Mrs Thatcher was rather annoyed with the over-zealous officials who caused the four military personnel to be arrested in Britain. Rightly, she refused to accede to the South African embassy's demand for the case to be dropped but she was keen for the embassy to know precisely how the legal hurdles governing their release and the return of their passports could be swiftly overcome. Thus the First Secretary at the embassy stood bail for the "Coventry Four", having declared in court that he was waiving his diplomatic immunity. (The embassy did not, however, formally confirm the waiver.) Then a petition to an English Judge in Chambers secured the repatriation of the four accused. Clearly, Mrs Thatcher wanted the four high-profile detainees safely out of UK jurisdiction, back in South Africa and off the agenda well before her June 1984 talks at Chequers with the two visiting Bothas ([[P W Botha]] and [[Pik Botha]]). Strange that [[Pik Botha]], the foreign minister, was able to find an excuse for not allowing the "Coventry Four" to stand trial in the Autumn of 1984. Stranger still that Mrs Thatcher failed to denounce Mr Botha's refusal to surrender the four 'terrorists' (cf declaration by U.S. Governor Michael Dukakis that South Africa is a 'terrorist state' <ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/1988/06/13/us/dukakis-backers-agree-platform-will-call-south-africa-terrorist.html Dukakis Backers Agree Platform Will Call South Africa 'Terrorist']</ref>)."</blockquote> | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 16:52, 12 April 2013

Four South African alleged arms smugglers were arrested by HM Customs & Excise officers in Coventry in March 1984 and charged with conspiring to export arms from Britain to apartheid South Africa in contravention of the mandatory UN arms embargo.[1] They became known as the Coventry Four.[2][3]

Contents

Smuggling activities

The four South Africans plus three Britons were charged in the Coventry Magistrates Court on 2 April 1984 with conspiring to export to South Africa high pressure gas cylinders, radar magnetrons, aircraft parts and other military equipment[4][5] in violation of the mandatory arms embargo imposed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 418. The uncovering of their smuggling operation and subsequent arrest followed the discovery of a shipment of artillery elevating gears at Birmingham International Airport in 1984.

The "Coventry Four" were Hendrik Jacobus Botha, Stephanus Johannes de Jager, William Randolph Metelerkamp and Jacobus Le Grange. In the front company, McNay Pty Ltd, they operated on behalf of Kentron. Metelerkamp was the Managing Director, Botha was in charge of administration and security, De Jager was the company accountant, while Le Grange was the technical expert.[4] One of the ways in which they worked around the international arms embargo was for Le Grange to travel to the United States to source military materiel - this would subsequently be imported by Fosse Way Securities in the UK, before being shipped onwards to South Africa via other countries.[4]

A fifth man, professor Johannes Cloete of Stellenbosch University – a key player in South Africa's missile development program – was arrested at the same time as the Coventry Four. But, according to The Guardian of 17 December 1988, Cloete's arrest was quickly followed by his release without charge on instructions from senior Whitehall officials.

The three British men arrested at the same time were Michael Swann, Derek Salt and Michael Henry Gardiner.[5] Salt had previously been dismissed from another company for manufacturing ammunition dies for the South African military, which he concealed as sewing machine equipment. After his dismissal, Salt continued to deal with Armscor, despite the international arms embargo. His company in Coventry manufactured mortar casings to Armscor's specifications, and also sub-contracted the manufacture of the high-precision artillery gears seized by HM Customs to a German company.[4]

Remanded in custody

The "Coventry Four" were remanded in custody and their passports confiscated. After several weeks, they were released on bail of £200,000 when André Pelser, 1st Secretary at the South African embassy, waived his diplomatic immunity and stood surety. Then, following an alleged intervention from 10 Downing Street, they applied to a Judge sitting in Chambers to recover their passports. In an unusual ruling which allowed accused criminals to leave the jurisdiction, Judge Lennard agreed the men could go home on condition they returned for the next court hearing in June. Bail was doubled to £400,000.

The four turned up in June for another remand, but South Africa then found a reason to avoid a trial.

Controversial visit

On 2 June 1984, British prime minister Margaret Thatcher controversially invited South Africa's president P W Botha and foreign minister Pik Botha to a meeting at Chequers in an effort to stave off growing international pressure for the imposition of economic sanctions against South Africa, where both the U.S. and Britain had invested heavily. Although not officially on the meeting's agenda, the "Coventry Four" affair clouded both the proceedings at Chequers and Britain's bilateral diplomatic relations with South Africa.[6]

Quid pro quo

In August 1984, when anti-apartheid activists – threatened with arrest in South Africa – took refuge in the British consulate in Durban, Pik Botha decided to retaliate by refusing to allow the "Coventry Four" to return to Britain to stand trial.[7] Foreign Office minister, Malcolm Rifkind, reported to the House of Commons that the South African government was wholly to blame for the men's non-appearance in a British court, and that Pretoria should cooperate. In the event the men did not come back to stand trial and no action was taken against South Africa.[8]

Bail forfeited

When the case came up again at Coventry magistrates in October, counsel for the South African Government, Mr George Carman QC, said: "They were simply obeying the expressed intention of their own government." Mr Pelser, who remained at the embassy for another two years, agreed to forfeit the bail money.

Salt was given a 10-month jail sentence and fined £25,000 for his part in the operation, while the UK companies involved paid fines of £193,000.[4][9]

Thatcher critic

In August 1989, British diplomat Patrick Haseldine was dismissed for publicly criticising Mrs Thatcher in the press of double standards over the release of the "Coventry Four".

Text of Haseldine's letter:[10][11][12][13]

"It is all very well for Mrs Thatcher to inveigh against the Belgians and the Irish with such self-righteous invective. Naturally, she would not care to admit it but in the not too distant past her allegations of being soft on terrorism and allowing political considerations to override the due legal process could have been levelled at Mrs Thatcher herself. Remember the "Coventry Four"? These were the four (white) South Africans brought before Coventry magistrates in March 1984 and remanded in custody on arms embargo charges. Rumour has it that Mrs Thatcher was rather annoyed with the over-zealous officials who caused the four military personnel to be arrested in Britain. Rightly, she refused to accede to the South African embassy's demand for the case to be dropped but she was keen for the embassy to know precisely how the legal hurdles governing their release and the return of their passports could be swiftly overcome. Thus the First Secretary at the embassy stood bail for the "Coventry Four", having declared in court that he was waiving his diplomatic immunity. (The embassy did not, however, formally confirm the waiver.) Then a petition to an English Judge in Chambers secured the repatriation of the four accused. Clearly, Mrs Thatcher wanted the four high-profile detainees safely out of UK jurisdiction, back in South Africa and off the agenda well before her June 1984 talks at Chequers with the two visiting Bothas (P W Botha and Pik Botha). Strange that Pik Botha, the foreign minister, was able to find an excuse for not allowing the "Coventry Four" to stand trial in the Autumn of 1984. Stranger still that Mrs Thatcher failed to denounce Mr Botha's refusal to surrender the four 'terrorists' (cf declaration by U.S. Governor Michael Dukakis that South Africa is a 'terrorist state' [14])."

See also

- Gerald Bull, imprisoned for smuggling artillery technology to South Africa

- South Africa and weapons of mass destruction

- Vela Incident

References

- ↑ Text of UNSCR 418 of 1977

- ↑ Coventry Evening Standard 31 March 1984 reporting the arrest and detention of the Coventry Four

- ↑ "The double standards on terrorism"

- ↑ a b c d e Jacklyn Cock, Laurie Nathan (1989). War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa. New Africa Books. ISBN 978-0-86486-115-3.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ a b "Statement Before the Security Council Committee Established by Resolution 421 (1977) Concerning the Question of South Africa". African National Congress. 1984-04-09.Page Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css must have content model "Sanitized CSS" for TemplateStyles (current model is "Scribunto").

- ↑ "From Chequers to Lockerbie: Botha's murderous journey"

- ↑ The Guardian 13 December 1988 Letters Geoffrey Bindman Shabby manoeuvres that aid and abet Botha

- ↑ The Guardian 17 December 1988

- ↑ "How SA arms team evaded British trial"

- ↑ Letter to The Guardian December 7, 1988

- ↑ "Fresh facts support PM's critic"

- ↑ "Sacked Thatcher critic sues ministry"

- ↑

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}} - ↑ Dukakis Backers Agree Platform Will Call South Africa 'Terrorist'

Wikipedia is not affiliated with Wikispooks. Original page source here