Yellowcake

Yellowcake (also called Urania) is a uranium concentrate powder obtained as an intermediate step in the processing of uranium ores. Yellowcake concentrates are prepared by various extraction and refining methods, depending on the types of ore. Typically, Yellowcake is obtained through the milling and chemical processing of uranium ore forming a coarse powder which has a pungent smell, is insoluble in water and contains about 80% uranium oxide, which melts at approximately 2880 °C.

Yellowcake is generally used to produce commercial nuclear materials, such as fuel elements in nuclear reactors that use un-enriched uranium. Known for its yellow colour during early mining operations, Yellowcake can be further processed into uranium enriched in the isotope U-235. In this process, the uranium is combined with fluorine to form uranium hexafluoride gas (UF6). Next, that undergoes isotope separation through the process of gaseous diffusion, or in a gas centrifuge. This can produce low-enriched uranium containing up to 20% U-235 that is suitable for use in most large civilian electric-power reactors (some nuclear power reactor designs such as CANDU heavy water reactors use natural uranium oxides with <1% U-235 as fuel).

With further processing one obtains highly enriched uranium, containing 20% or more U-235, that is suitable for use in compact nuclear reactors—usually used to power naval warships and submarines. Further processing can yield weapons-grade uranium with U-235 levels usually above 90%, suitable for nuclear weapons.

Yellowcake is produced by all countries in which uranium ore is mined.[1]

Contents

Namibian Yellowcake

In 1976, Rössing Uranium Limited began operations by exporting Namibian Yellowcake (processed uranium ore). The Rössing Uranium Mine is jointly owned by British mining conglomerate Rio Tinto Group (RTZ), by the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran (AEOI), by the South African parastatal entity known as the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), which also controlled most of the voting shares, and by the French-based Total Compagnie Minière (TCF). Before the Rössing Uranium Mine opened, RTZ had managed to secure large long-term contracts with German and Japanese utilities and with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). Within a very short time, the Rössing mine had become the largest open pit uranium producer in the world.

On some readings of international law, the Rössing Uranium Mine operation was illegal right from the start since apartheid South Africa was continuing to occupy Namibia in defiance of UN Security Council Resolution 435.[2] The UN had formally ended South Africa’s mandate to govern the territory in 1966 by transferring that mandate to the newly created UN Council for Namibia (UNCN) pending the country's independence, and demanded the immediate withdrawal of South African troops. In 1971 the International Court of Justice ruled that these UN measures were binding and in 1973 the UN General Assembly recognised the freedom-fighting South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) as the "sole authentic representative" of the Namibian people.

Illegal mining

In 1974 the UN Council for Namibia issued Decree № 1, which prohibited the extraction and distribution of any natural resource from Namibian territory without the UNCN’s explicit permission, provided for the seizure of any illegally exported material, and warned that violators could be held liable for damages. Projected to be Namibia’s largest mining operation, Rössing thus became the primary target of Decree № 1. However, many Western governments (including the US and Britain) refused to accept Decree № 1 as binding, with lawyers and government officials disputing whether the decree was juridically sound, whether and how it might apply, and which courts might enforce its application. But the bottom line was that Rössing aimed to supply at least 10 percent of the global uranium market which translated into one-third of Britain’s needs, and probably more for Japan. Decree № 1 therefore sparked a lengthy international struggle over the legitimacy of Rössing uranium.

Starting in 1975, the UNCN sent out numerous delegations to convince governments to suspend their dealings with Namibia. They heard many expressions of support for the independence process, but prior to the mid-1980s only Sweden (among the large Western uranium consumers) pledged to boycott Rössing’s product. Activists stepped up the pressure in a wide variety of forums. In the UK and the Netherlands, they joined forces with the anti-nuclear movement, resulting in organisations like the British CANUC (Campaign Against the Namibian Uranium Contracts).

"Follow The Yellowcake Road"

On 10 March 1980, Thames Television broadcast a documentary film entitled "Follow The Yellowcake Road":

- World In Action investigates the secret contract and operation arranged by British-based Rio Tinto Zinc Corp to import into Britain uranium (Yellowcake) from the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia, one of whose major shareholders is the South African government. This contract having received the blessing of the British government is now compromising its position in the United Nations negotiations to remove apartheid South Africa from Namibia, which it is illegally occupying.[3]

The UN Council for Namibia held a week-long hearing in July 1980, during which experts and activists from Europe, Japan, and the United States gave presentations on Rössing’s operations and contracts, and the TV documentary "Follow the Yellowcake Road" was screened. Testimony focused on the relationship between southern Africa and the Western nuclear industry, arguing that all purchases of Namibian uranium effectively supported the colonial occupation via the taxes paid by the Rössing Uranium Mine.[4]

Ownership and Control

Shares in the Rössing Uranium Mine are owned 69% by the Rio Tinto Group, 15% by the Government of Iran (purchased in 1976), 10% by IDC of South Africa, 3% by the Government of Namibia (with 51% of voting rights), and 3% by local individual shareholders.[5]

Although Rössing's part-ownership by Iran was the cause of controversy in the 1970s and 1980s, the Namibian Government – in power since 1990 – has denied supplying Iran with Namibian uranium, which could be used for nuclear weapons.[6]

In an analysis of global uranium supply and demand, one economist (Stephen Ritterbus) noted that southern African uranium "could account for as much as 50 per cent of the total available for net export." Reminding his audience that South African (IDC) shares in Rössing gave the apartheid state voting control of the company, Ritterbus suggested that Pretoria thereby had "leverage not only as regards the supply and price of uranium but also as regards the formulation of foreign policy towards South Africa itself and [its] present position in Namibia."

In 1981, SWAPO helped organise a seminar for West European trade unions as well as presentations on living and working conditions at Rössing and on the mine’s paramilitary security forces, which appealed to the loyalties of the International Socialist movement. The seminar detailed the secret movements of Rössing uranium through European planes, ships, docks, and roads, noting that European transport workers had unknowingly handled barrels of radioactive substances. A 1982 seminar organised by the American Committee on Africa on the role of transnational corporations in Namibia focused heavily on uranium, reprising many of the arguments mounted by European activists. In subsequent years CANUC redoubled its efforts to enlist the British peace movement.

RTZ Mineral Services

Despite all the bad publicity, Rössing’s customers held firm in their contracts through the mid-1980s. The company helped: it responded to the pressure by papering over the transnational dimensions of its operations. To address "the unwillingness of certain customers to deal direct," RTZ set up a front company in Switzerland under the name RTZ Mineral Services (Minserve). Customers could thus sign contracts that didn’t mention Rössing, whereupon Minserve would sign corresponding "back-to-back" contracts with the mine. Minserve’s marketing emphasised that RTZ owned uranium mines in three countries: should one mine prove unable to deliver, ore from elsewhere could take its place. Management referred to customers by number rather than name to reinforce discretion. This protected not just Rössing’s customers but also its board of directors, who officially remained ignorant of customer identity and contract prices. Until late 1985 (when the threat of sanctions made such topics impossible to ignore), the "market reports" Minserve delivered at company board meetings in Namibia’s capital Windhoek pointedly avoided discussing how anti-apartheid activism was constraining Rössing’s business. The omission was especially glaring because the reports discussed just about every other international political development affecting the flow of uranium.

Nevertheless, records of Minserve’s London sales meetings show that customers began expressing unease in the early 1980s. Japanese utilities in particular worried that their government might cave to international pressure and began asking Minserve to substitute non-Namibian origin material. In order to secure new contracts, Minserve had to devise increasingly arcane arrangements. In September 1983, for example, one customer who had previously held a direct contract with Rössing made a new inquiry. A sales associate reported: "Politically [they] cannot buy Namibian material but they are willing to discuss taking swapped material in the form of spot deliveries of UF6 [uranium hexafluoride, the feed for enrichment plants]. Any contract should preferably be with a third party, either the converter or the contracting party and not an RTZ Company."

Minserve’s role as a front was an open secret, and utilities increasingly sought to maximize their distance from RTZ. As international pressure for Namibian independence mounted, Rössing and Minserve began using "flag swaps" to fulfil contracts. Such arrangements could follow several scenarios. In one, the material would be re-labelled by conversion plants. Comurhex (in France) and BNFL (in Britain) proved particularly co-operative: after they converted Rössing’s yellowcake into uranium hexafluoride, they would state its origin as French or British on the customs forms accompanying the material to US enrichment plants. In a second scenario, Minserve would swap contracts with another RTZ customer: the contract originally intended to use Rössing Yellowcake would get filled with uranium from another RTZ mine, while the contract signed by that mine would get filled with Rössing uranium. This scenario depended on the willingness of the other RTZ customer to accept Namibian uranium; Swiss utilities usually obliged happily. Yet another scenario involved two conversion plants shuffling titles to uranium oxide and hexafluoride. All told, the quantity of swapped material rose from several hundred tonnes in 1982 to several thousand by 1985–1986.

At first, the pressures that made Rössing uranium increasingly illicit also made it more profitable. Sales contracts were denominated in US$ but most costs were incurred in South African Rand. As opposition to apartheid drove down the value of the Rand, profits mounted: in 1985 Rössing showed the highest profit to date, recorded at over 190 million Rand after taxes. This was especially remarkable given "the continued weakness in the world uranium market." Still, a favourable exchange rate would not help if Rössing lost all its buyers. Talks on Namibian independence had stalled and South African state violence had intensified. In 1985 even the staunchest allies of the apartheid state began discussing full-scale mandatory sanctions. Rössing didn’t fret too much about interruptions to its supply chain, since it could circumvent restrictions with purchasing agents, offshore accounts, and more front companies. But Minserve did worry about specific prohibitions on the import of Namibian uranium: Rössing’s main customers had "enough of the product and could manage quite well without buying any more. [They] might welcome an excuse to renege on their contract."

At best, flag swaps and related measures would only give Rössing some breathing space. "We have to accept that in any coordinated imposition of sanctions uranium is the easiest material for the authorities to trace and block. Without the assistance of the converter or the falsification of origin records it is inevitable that the sales of Rössing material will be severely curtailed. Any study on the counter effects of sanctions on Rössing has therefore to be one of damage limitation."

Evading US anti-apartheid legislation

One form of damage limitation involved working the finer points of anti-apartheid legislation, particularly after the US Congress overrode President Reagan’s veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act (CAAA) in October 1986. The CAAA's threat to Rössing were considerable: a significant portion of its yellowcake went to plants in America for conversion to hexafluoride. In addition, much of Rössing’s Yellowcake converted elsewhere went to US plants for enrichment. Stopping the flow of Namibian-origin uranium oxide or hexafluoride through US plants could therefore shut down Rössing’s business altogether. To help work around the bill, Minserve hired the consulting firm Wrightmon USA for a monthly retainer of $15,000.

Diane Harmon, the firm’s president, employed a double strategy to maximize the amount of Namibian uranium imported into America. On the one hand, she formed an alliance with US conversion plants which stood to lose a lot of money if Rössing’s business disappeared. On the other hand, she also exploited a loophole in the CAAA that went against the interests of the converters. Rössing Yellowcake that entered the US directly clearly counted as Namibian. But if that Yellowcake got converted and re-labelled as British UF6, hadn’t its nationality changed? In which case, surely it could enter the US as enrichment feed? If Rössing transferred all its conversion business to European plants, its customers could maintain their US enrichment contracts. Harmon pointed out that US enrichment plants would suffer if they lost southern African feed; combined with other import restrictions, the impact might force one of the plants to close. Job losses would ensue. By the end of 1987, Harmon had obtained a ruling that: South African–origin uranium ore and uranium oxide that is substantially transformed into another form of uranium in a country other than South Africa is not to be treated as South African uranium ore or uranium oxide and is therefore not barred. This became known as the "UF6 loophole." Pleased with this outcome, Minserve asked Sir Alistair Frame, RTZ’s well-connected chairman, to "have a word" with BNFL and the British Foreign Office to ensure that they continued to re-label converted material as UK-origin.

UNCN legal action

In May 1985, the United Nations Council for Namibia (UNCN) began legal action against URENCO - the joint Dutch/British/West German uranium enrichment company, with plants in Capenhurst (Cheshire, England), Almelo (Netherlands) and Gronau (West Germany). Since URENCO had been importing uranium ore from the Rössing Uranium Mine in Namibia, the company was charged with breaching UNCN Decree № 1. The case was expected to be ready by the end of 1985 but was delayed because URENCO argued that - despite having enriched uranium of Namibian origin since 1980 - it was impossible to tell where specific consignments came from. When the case finally reached court in July 1986, the Dutch government took URENCO's line, claiming not to have known where the uranium had been mined. [7] Upon the adjournment of the URENCO proceedings, SWAPO's UN representative, Helmut Angula, insisted that other companies, such as Shell, De Beers (Consolidated Diamond Mines), Newmont, and Rio Tinto were also likely to face prosecution for breaching the UN Council for Namibia Decree.

Bernt Carlsson lays down the law

The man responsible for Namibia under international law, Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations and UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, spoke about these prosecutions in a World In Action TV documentary "The Case of the Disappearing Diamonds" which was broadcast by Thames Television in September 1987:

- "The United Nations this year in July started legal action against one such company - the Dutch company URENCO which imports uranium."

When asked if he would be taking action against other companies such as De Beers, the diamond mining conglomerate, Bernt Carlsson replied:

- "All the companies which are carrying out activities in Namibia which have not been authorised by the United Nations are being studied at present. As far as De Beers is concerned, the corporation has been trying to skim the cream which means they have gone for the large diamonds at the expense of the steady pace. In this way they have really shortened the lifespan of the mines. One would expect from a worldwide corporation like De Beers and Anglo American that they would behave with an element of social and political responsibility. But their behaviour in the specific case of Namibia has been one of profit maximation regardless of its social, economic, political and even legal responsibility."[8]

Delay in closing the UF6 loophole

In 1988, US Congressional Democrats began working to close the UF6 loophole. The State Department’s Office of Non-proliferation and Export Policy did as well, declaring:

- "It is not possible to avoid the provisions of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act by swapping flags or obligations on natural uranium physically of South African origin before it enters the USA."

Nevertheless, Rössing managed to delay the implementation of restrictions which could have put it out of business. And - in the end - that delay sufficed: apartheid South Africa and other negotiating parties signed an independence accord on 22 December 1988. On his way to the signing of the agreement at UN headquarters in New York, UN Commissioner Bernt Carlsson became the highest profile victim of the Pan Am Flight 103 crash at Lockerbie on 21 December 1988.

URENCO case dropped

Following Bernt Carlsson's untimely death in the Lockerbie bombing, the case against URENCO was inexplicably dropped and no further prosecutions took place of the companies and countries that were in breach of the United Nations Council for Namibia Decree № 1. Despite this fairly obvious evidence that Bernt Carlsson was the prime target on Pan Am Flight 103, there has never been a murder investigation conducted by the CIA, FBI, Scottish Police or indeed by the United Nations. Instead, fabricated evidence has been used to frame and wrongfully convict the Libyan Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for the crime of Lockerbie.[9]

Margaret Thatcher pays a visit

Four months after Bernt Carlsson was killed at Lockerbie, Margaret Thatcher - then Britain's prime minister - went to visit the Rössing Uranium Mine in March 1989 and commented that the project made her "proud to be British". Mrs Thatcher was accompanied on this visit to the Rössing Uranium Mine by current prime minister David Cameron - then a young researcher from Conservative Central Office.[10]

URENCO privatisation

On 22 April 2013, David Cameron's coalition government announced plans to sell its share in URENCO - the uranium enrichment company owned by Britain, Germany and the Netherlands - unleashing a new wave of privatisations in an attempt to cut the public debt. The UK government’s one-third share in URENCO could fetch up to £3bn, making it one of the biggest privatisations in the UK in years.[11]

Headquartered in the semi-rural Buckinghamshire village of Stoke Poges, where, appropriately enough given its atomic plot, "Goldfinger" was partly shot, URENCO has a 31 per cent share of the world's uranium enrichment market. This provides the fuel for nuclear power utilities and URENCO has enrichment plants in the US and the three investor countries, including one in Capenhurst, Cheshire.

- "It's a ridiculous idea," according to the GMB union's national secretary for energy Gary Smith, who earlier this week complained to The Independent of the prospect of the Chinese investing in the nuclear new-build programme. "We're flogging off precious nuclear assets instead of developing a strategy around nuclear. It's absolute madness."[12]

By privatising URENCO, the British government is presumably hoping to bring closure to the Lockerbie affair, and thus escape prosecution for the Thatcher administration's criminal behaviour in processing Namibian yellowcake contrary to United Nations Council for Namibia (UNCN) Decree № 1.

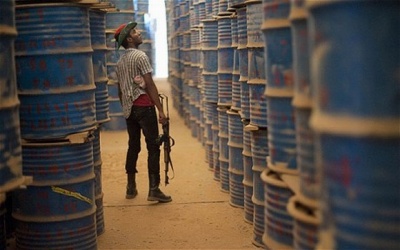

Libyan Yellowcake

An estimated 6,400 barrels of Yellowcake uranium were discovered near the Muammar Gaddafi stronghold of Sabha towards the end of the uprising that resulted in the ruler’s death in October 2011. The powder they contain appears to be Yellowcake uranium from neighbouring Niger. Yet when they were discovered by advancing rebel forces, they were abandoned, in tumbledown warehouses protected only by a low wall. Niger mines Yellowcake under a strict security regime designed to ensure none of it falls into the hands of illicit networks. But post-Gaddafi Libya affords little or no protection to this vast haul of material, which if refined to high levels of purity is the essential element of a nuclear bomb.

The UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has performed an inventory of the stock – which is kept in an ordinary warehouse, next to an estimated 4,000 surface-to-air missiles previously procured from Russia – and technically maintains control over it.

Yet a report from a visiting Times newspaper journalist in October 2013 alleged that the stockpile was in the control of a local weapons dealer, and his men did not even guard the warehouse for fear of suffering radiation poisoning.

"We have no use for the yellow uranium ourselves and are frightened of it," said Bharuddin Midhoun Arifi, a commander of 2000 fighters in Sabha. "My men don't like guarding the site as they believe it will make their skin fall off. So we guard it from a nearby checkpoint. Maybe someone could steal one or two drums if they wanted, but not more."

According to the militia commander, the security vacuum left following the death of Colonel Gaddafi is now attracting Al-Qaeda, which is seeking weapons.

"Qa'ida come to visit me, asking to buy weapons, asking for heat-seeking missiles, asking for uranium," Arifi said. "It started this year when the French sent troops to chase them out of Mali. Qa'ida came to Sabha asking for medical supplies. They received some. Next they came back asking for weapons," including surface-to-air missiles capable of shooting down a passenger aircraft.

A former commander of the British military's chemical defence regiment, Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, told Russia Today that the fact that Libya has so much of this Yellowcake uranium is a concern.

"If Al Qaeda did get hold of this Yellowcake it potentially could be used for a radiological explosive device. One would expect that security agencies around the world would be looking very closely at this to ensure that Yellowcake is secured in Libya and any potential proliferation of it outside of Libya is looked at very closely indeed."

Despite The Times report, Libyan Foreign Minister Mohamed Abdelaziz in September claimed the stockpile in Sabha has been secured with the help of IAEA inspectors.

"Libya is trying to determine if the concentrated uranium can be used for peaceful nuclear energy purposes or sold to countries which use the product for peaceful purposes," said the minister.

Yet the Centre for Strategic Studies in Tripoli had previously asked the Libyan authorities to use the uranium for "industrial and agricultural development and in the production of clean energy."[13][14][15]

References

- ↑ "What Is Yellowcake, Anyway?"

- ↑ "UN Security Council Resolution 435 of 29 September 1978"

- ↑ "WORLD IN ACTION (FOLLOW THE YELLOWCAKE ROAD)"

- ↑ "The Gulliver Rössing Uranium Ltd Dossier"

- ↑ "Rössing's business at a glance – 2007"

- ↑ "Iran did not buy uranium from Namibia" – The Namibian, 1 February 2005

- ↑ David de Beer, The Netherlands, Namibian uranium and the Implementation of Decree No. 1, Working Group Kairos, Brussels, 1986

- ↑ "Bernt Carlsson and the Case of the Disappearing Diamonds"

- ↑ "Fragment of the imagination?"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Cameron's Nuclear Secret"

- ↑ "UK pushes ahead with URENCO privatisation"

- ↑ "URENCO move: Shadow over next big state sell-off"

- ↑ "Russia implores UN to take control of Libya’s ‘unguarded’ yellowcake uranium"

- ↑ "Dumped in the desert ... Gaddafi’s yellowcake stockpile"

- ↑ "UN envoy says 6,400 barrels of yellowcake is stored in Libya"