Hermitage Capital Management

(Investment fund, Asset management company) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Formation | 1996 |

| Founder | • Bill Browder • Edmond Safra |

| Headquarters | Guernsey |

| Interest of | Martin Armstrong, Andrei Nekrasov |

| Exposed by | Alexander Perepilichny |

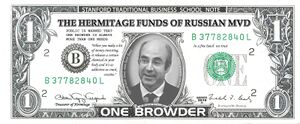

Hermitage Capital Management is an investment fund and asset management company which had a specialization geared towards Russian markets in the 90s. It was founded by Bill Browder and Edmond Safra. It's headquarters are in Guernsey, with offices in the Cayman Islands, London and Moscow. Its main tactics included the exposure of corporate corruption in the companies it is holding.

Activities in Russia

Their primary strategy was to buy shares of a big undervalued company (preferably energy and/or state-affiliated) and then start digging up information about what they perceived as ineffectiveness in the governance of the company. Upon discovering any irregularities, Browder used a wide array of methods to draw attention to his cause: articles in The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal and its Russia subsidiary Vedomosti; lawsuits, even political influence in the Western countries. More often than not such action compelled the company to correct its policy, the market positively appraised those changes, and the worth of HCM’s stake would increase. Browder himself proudly dubbed that process the “Hermitage Effect”. But this is only one side of the story, the one which HCM prefers to spin. To understand the other, a clear view of what the Russian financial market was is required. With only a handful of major players, not bounded by any real laws against insider trading, it was the ideal muddy water for the boldest manipulations. Given the immaturity of the Russian legal system at the time, the majority of corporations often operated in “grey” areas and was extremely vulnerable to legal pressure. In 1999 Safra died under mysterious circumstances, having shortly before sold the ownership of HCM to HSBC, one the largest banking and financial services groups in the world. Lobbying and legal options at Browder’s disposal only increased. Unfortunately, he didn’t hesitate to use it, often overstepping the boundary between shareholder activism and greenmail.

During the fund’s operation in Russia, they filed more than 40 lawsuits, winning only 6 of them. Whilst some of them indeed contested obvious scams, as in Sidanko’s case, others were of a dubious nature at best. For example, in 2001 Sberbank, the biggest and state-owned bank in Russia, intended to issue additional shares by public subscription; HCM tried to block this decision. According to Russian law, the Central Bank must own no less than 50% plus one share of Sberbank. It was common knowledge that it would have to buy a part of the additional issue, in order to not violate this law. Immediately after the beginning of the offering, a group of minority shareholders led by Browder brought an action against Sberbank, demanding it be canceled. They claimed that: 1) since it was common knowledge that one of the owners had to participate in the subscription, therefore it was private, not public; and 2) that made the representatives of the Central Bank that were on the supervisory board an interested party, so the issue had to be approved by the general shareholders’ meeting. Browder lost this case, but it certainly negatively affected the offering. Another example: the fund filed a lawsuit against Surgutneftegas in 2003, demanding that the oil company buy shares owned by its subsidiary. While the law clearly forbids companies owning their own shares, it doesn’t say anything about subsidiaries. HCM argued that it’s basically the same thing, conveniently forgetting about the business entity convention.

By 2004, HCM became the biggest foreign investment fund in Russia; it was managing 3.5 billion dollars, representing more than 6000 investors. And it was very successful as well – the annual average return amounted to 34.5%, even factoring in the drop in 1998 (the Russian stock index RTS grew only half as fast). Browder himself earned more than $120 million by various estimates. The fund also enjoyed enormous influence in Russia. HCM forced the change of energy giant RAO UES’s reform plans, participated in the ousting of Gazprom former all-powerful CEO Vyakhirev and even prevented Rosneft from consolidating the shares of its subsidiaries. Let’s recall that Rosneft is considered to be the realm of Igor Sechin, who – according to the Western media – destroyed YUKOS on a whim. So finally, every major player in Russia was running out of toes that Browder hadn’t stomped yet. And it’s no wonder they decided to take a closer look at Hermitage’s activity as well.[1]