Document:The Integrity Initiative Guide to Countering Russian Disinformation

| A guide to Russian disinformation, an ideological prep guide for dedicated II operatives |

Subjects: Integrity Initiative, Clusters, propaganda, influence operation

Example of: Integrity Initiative/Leak/1

Source: 'Anonymous' (Link)

Straight telling of facts and opponents actual views is not a strong point of II-analyses; every example picks only outré claims ('the mother-in-law did it') over real hard criticism of the US/British narrative. Conflation of Russian government efforts and misc. stuff found on the internet. Conspiracy theories are OK for II as long as they confirm US/British narrative.

★ Start a Discussion about this document

The Integrity Initiative Guide to Countering Russian Disinformation

Contents

Introduction: “No smoke without fire"

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, everyone who is a consumer or originator of any media, from traditional means such as newspapers or broadcasting to modern social media, is aware of the issue of “disinformation”. They may use a different term to describe it, such as “fake news”, “false news”, or “alternative facts” (notably following the election of Donald Trump as US President, who, along with his spokespersons, has used such terms when attacking the media or justifying his more curious reports), but what all these terms signify is the same: a deliberate attempt to mislead people by giving them at best an edited version of the truth, at worst total lies.[1]

To continue the American scenario, one example of the former is Trump claiming that most Americans voted for him in the Presidential Election. Trump became President because the American system of counting the Electoral College votes, rather than the number of individual votes, worked in his favour; more Americans actually voted for Hilary Clinton than for Trump. So looked at in this light, Trump’s claim to have won the popular vote is an edited version of the truth. [2]

An example of the total lie came just after Trump’s inauguration as President. The then Presidential spokesman, Sean Spicer, claimed at his first press conference (with a totally straight face) that more people had attended the inauguration than had attended the ceremony in 2009 when Barack Obama was sworn in as President. A simple comparison of photos taken from the same spot looking towards the Capitol Building and the podium showed that Spicer was talking nonsense (Fig.1). So absurd was the claim that many people laughed it off. Others, though, saw this as a warning sign: if Trump’s spokesman could lie about this (and apparently not care when it was so easily disproved), what could we expect in the future?

Fig.1 US Presidential inauguration photos. The absurdity of the claim that more people attended Trump’s inauguration is there for all to see.

Spicer’s demeanour was crucial to the peddling of the lie. Had there been a sly smile or a twinkle in the eye it would have been clear that he was playing a game with his audience and they would not have been expected to believe the nonsense he was spouting. But by maintaining a completely serious expression, Spicer actually encouraged some to doubt the evidence of their own eyes. As we shall see, maintaining the mask of seriousness is something which purveyors of disinformation, notably those from the Kremlin, have mastered.

Whilst the above example is clear, the waters are muddied when the purveyors of disinformation start using the term (or its substitutes, such as “fake news”) to try to discredit genuine facts. This is a disturbing trend which the Trump administration has made something of a specialty. Accusing others of pedaling disinformation is a common trick of the disinformers. It illustrates the need for careful checking of sources.

What makes Trump’s “fake news” worse is that it confirms in many people’s minds in the West that America is not to be trusted; and this was already a key element in Russia’s disinformation campaign. An old principle of Soviet propaganda was that it would be easier to convince people to believe it if it contained an element of truth. And the Kremlin knows that many people in the West do not trust the USA and its intentions.

So when Russian troops seized Crimea and invaded Eastern Ukraine in the spring of 2014 – the point at which the intense Russian disinformation campaign began – there were plenty of people in Russia and the West who were ready to accept such Russian lies as: had the Russians not taken Crimea it would have become a base for the US Navy; that it was the CIA which was behind the demonstrations in Kiev which sparked the Ukrainian Revolution; and that the US Army was equipping and training the Ukrainian Army. Because of other American interventions around the world, the Russians played on the notion that “there’s no smoke without fire”, thus achieving the first goal of disinformation: not necessarily to convince people that what was being said was true, but that they wouldn’t know if anything they heard was true, so it was better to be skeptical about all of it.

It is frequently the case that disinformation is not intended to be believed by the target audience. It is usually sufficient for the disinformation to sow sufficient doubt in the minds of the recipients that they refuse to believe anything that they hear about a particular incident. When people start to say, “You don’t know what to believe” or “They’re all as bad as each other”, the disinformers are winning.

The Russian lies around the seizure of Crimea are a vivid example of this. When masked men in unmarked but clearly new and correct military uniforms appeared in Crimea in February 2014 (Fig.2) – and were quickly dubbed, “little green men” – President Putin denied any knowledge of who they were or that their presence had anything to do with him. This helped play into the narrative which the Russians were spreading about the role of the USA and the desire of everyone in Eastern Ukraine to join with Russia. A year later, in a documentary film shown on Russian television to mark one year of Crimea being “back in the Russian fold”, Putin boasted openly that he had given the order for the troops to take Crimea, after an all-night sitting of the Russian government. This was a clear admission that in 2014 he had been lying. But far too few Western news outlets (and no Russian ones) picked him up on this.

Fig.2 “Little Green Men” in Crimea. “Nothing to do with me”, said Putin in 2014; “I gave the order”, he said a year later.

There are two crucial differences between Trump’s fake news and Russian disinformation. Firstly, American media outlets can openly criticize the President and even mock what Trump or his spokespersons say (such as, for example, the satirical column, The Borowitz Report, in The New Yorker magazine, which frequently pours scorn on Trump; see Fig.3) In case anyone was in any doubt as to the authenticity of what Borowitz writes, the column is flagged up as “satire” and carries the line, Not the news.

Fig.3 A typical title and opening sentence from Andy Borowitz in The New Yorker; 24 April 2017. The article went on to mock Trump’s poor English and reliance on tweets, whereas Obama’s “sentences had both nouns and verbs in them”.

It is not possible to imagine Russian media publishing such an article about Putin. The Russian President clamped down on any criticism by closing down critical television programmes shortly after becoming President in March 2000, including the Russian satirical puppet show, Kukly, which had made fun of President Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s and had already produced a Putin puppet.

But even more significant is that while Trump may have a few press people and spin doctors to put out some dubious messages, Putin has overseen the creation of so-called “troll factories” employing thousands of people to send out and duplicate examples of Russian disinformation. And in the Armed Forces there is now a new branch: Information Troops. Their existence was long suspected by Western intelligence services, and was acknowledged by Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu when updating the State Duma on defence matters on 22 February 2017. As Shoigu said at an awards ceremony a month later, “The day has come when we all have to admit that a word, a camera, a photo, the Internet, and information in general have become yet another type of weapons, yet another component of the armed forces.” [3] What the Kremlin is overseeing is not simply “fake news”; it is the organised production of disinformation on an industrial scale.

Why does it happen?

Disinformation has long been used as a weapon of war, even if the actual term has come into wide use only recently.[4] Often it has been termed “propaganda”. The use of propaganda to try to boost the morale of one’s own side and sap the morale of the enemy has been used for centuries. But propaganda – like many other weapons of war – took on a new meaning in the First World War. A new method for delivering propaganda was by dropping thousands of leaflets on enemy troops from the recently-developed airplanes.[5]

In the Second World War, the propaganda became more sophisticated, although leaflets were still dropped on enemy troops to try to lower their resolve to fight. One of the best known methods was the use of radio broadcasts aimed at the British and American publics by William Joyce. Joyce was born in America, raised in Ireland and in the late-1930s became a leading member of the British Union of Fascists. Tipped off that he was about to be interned in late August 1939, he fled to Germany where he was granted citizenship. In February 1940 he took over broadcasting pro-German propaganda, and in Britain and America was given the nickname (previously applied to his predecessor), “Lord Haw-Haw”. This mocking title shows that propaganda is not always successful.

What air-dropped leaflets in World War One and radio broadcasts in World War Two illustrate is that propaganda has always been quick to adapt to new technologies and methods; and what is happening in the twenty-first century is another example of that. But the advances in technology in recent years are much greater than those that took place in the two decades between the world wars. The disinformers have been quick to realise this. Furthermore, the rapid pace in technological development has coincided with a crisis of confidence among many in the West in our institutions and media. Many people are ready to believe an alternative view of events. This has been heightened by the nonsense which emanates from the White House via Donald Trump’s Twitter feed. The disinformers understand this, too.

As if this were not enough, developments in the media in the past two decades have made the problem worse. If the media picture in the late twentieth century was generally a question of newspapers and broadcast media staffed by experienced journalists who took responsibility for what they wrote, nowadays thanks to channels such as Facebook, Twitter and online blogs and podcasts anyone can give themselves the label of “journalist”, whether they have any experience or not and whether they take any responsibility for their words or not.

There is also a real battle among the mainstream media to be “first with the news”. And if this was a growing phenomenon in the early years of the century for broadcast media, now that newspapers have constantly updated websites they are part of the competition, too. As always, a clever or sensational headline can grab the reader’s attention. But if the reader does not go further and read the actual story, headlines can often be misleading; something else which has been latched onto by the purveyors of disinformation.

But why is Putin determined to bombard the West with disinformation at the same time as feeding his own people a diet of lies about the West’s intentions and his own regime? Few in the West would say that we are in a war with Russia. The Kremlin, however, disagrees. The Russian leadership specifically says that Russia is at war with the West.[6]

As well as seeing Russia as being at war with the West, Putin’s attitude has deep historical roots; and he is not going to change. Perhaps because geographically Russia is on the edge of Europe, it has always found itself on the fringes of European thought, too.

A major reason for this was religion. It may seem strange to go back a thousand years, but because of the Great Schism of 1054 between Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity, relations between East and West were strained for centuries. Despite Peter the Great’s attempts to bring Russia more into the mainstream of Europe, Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 did much to convince Russians that “the West” was an enemy not to be trusted.

In the twentieth century, the division between Russia and the West widened still further, not because of religious belief but because of political ideology. The Bolsheviks may have felt that they were in the vanguard of human development by creating the world’s first state governed by Communist beliefs; but it would be difficult to think of anything which could drive more of a wedge between Russia and the West than the juxtaposition of Capitalism and Communism. To make matters worse, the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941 was seen as being on a par with Napoleon’s invasion of 1812: both are referred to in Russian as wars for “the Fatherland”.

When the Communist system collapsed in 1991, Russia had a great deal of catching up to do – not just in material terms (although the USSR had been way behind the West in this sense), but more importantly in ideas, such as the rule of law, political pluralism, human rights, tolerance and diversity.

For many, it was the material side which mattered more; hence we see the ugly face of Russia’s survival-of-the-fittest crony capitalism of the 1990s: mass poverty; mafia; criminal gangs; theft of state assets; the rise of the oligarchs. Those who wanted to seize the opportunities presented by liberal ideas to turn Russia into “a normal, civilised country” (a view frequently expressed at the time) were, in the immediate term, at least, going to lose out. When those who believe in using violence to gain what they want hold the reins of power, it is difficult to defeat them with words and ideas only.

Fig.6 In the 1990s, the majority of Russians struggled to survive, queueing for basics or selling goods on the street; while mafia-style gangs ran protection rackets over such trade.

This became particularly true after representatives of the old Soviet power structures gained a stranglehold on power and wealth, notably those – like Putin – from the KGB or others from the so-called “power ministries”: the Armed Forces or the Interior Ministry, as well as the secret services. These are people who have no moral compass, and for whom liberal ideas are complete anathema, especially for Russia. They will make use of their power to ensure that they continue to enjoy the fruits of the country’s wealth, and then do everything to maintain that situation.

And “everything” means everything. These people attach no value to human life or higher human feelings, such as respect, dignity or honour outside their immediate circle. This can be applied to their own, Russian citizens. It is believed that Putin, when Prime Minister under an increasingly ailing Boris Yeltsin, ordered the blowing-up of apartment blocks in Moscow and other Russian cities in September 1999 to give him an excuse to blame this on Chechens and send the Russian Army back into Chechnya to make up for the humiliation the Army suffered in

1996 when it was forced to pull out of this rebellious republic with its tail between its legs. The Chechen rebellion was crushed in the most brutal fashion.[7]

Thousands of innocent civilians have been killed in Ukraine since Russian troops invaded the eastern part of that country in 2014; and thousands more have been killed in Syria because of both indiscriminate Russian bombing of that country and targetted bombing against “soft” targets such as hospitals.

Fig.7: Some of Putin’s greatest enemies have been those who have stood up for the truth. (L to R): Journalist Anna Politkovskaya; Politician Boris Nemtsov; ex-KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko. Each of them spoke out against Putin. Each of them was assassinated.

There have also been individual assassinations of the Kremlin’s enemies, at home and abroad. In Russia these include Anna Politkovskaya, shot in the lift of her block of flats in October 2006 and Boris Nemtsov, shot in the back just metres from the Kremlin in February 2015. Abroad, Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB agent, was killed on the Kremlin’s orders in London in 2006. The Kremlin is suspected of being behind another 14 apparent assassinations of Russians in Britain; and is widely believed to have attempted to kill the former double agent, Sergei Skripal, and his daughter in Salisbury in England in March 2018 (see below for details of the disinformation campaign surrounding this assassination attempt).

In order to protect his and his associates’ wealth and power, Putin believes that it is essential to “protect” the Russian population from liberal Western ideas which he considers as unsuitable for Russia. In actual fact, these ideas and values are unsuitable only for the desire of the Russian leadership to keep a grip on power and the benefits this brings them. So they put huge efforts into discrediting and destabilising the West, both to cause chaos in the West itself and to try to show their own people how fortunate they are to have a system which looks after them – as long as they remain subservient. Political warfare using all means possible, such as disinformation and cyber attacks, is not just a spin-off from this system; it is an essential element of it.

Another way in which Putin could justify his programme of disinformation (were he to admit that Russia does this which, despite all the evidence to the contrary, he doesn’t) would be to say that this is all aimed at re-establishing the glory of Mother Russia. The collapse of the Soviet Union was a huge shock for the Russian people. As the largest country in the world (geographically) and the world’s second superpower in Soviet times, the Russians suffered a double blow when the USSR was no more. Not only had large parts of what they had considered as their homeland suddenly become independent states, but overnight the prestige of being a superpower had vanished. [8]

When Putin came to power, one of his aims was to make his people believe that he was making Russia great again. This found true resonance with millions of his fellow countrymen. They would be prepared to put up with great hardships to see this happen; certainly they would be prepared to forego “democracy” to this end. What had the first attempts at playing with democracy in the 1990s brought them, but chaos? Furthermore, when the KGB set up the political party of the extreme nationalist, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, in 1990 they gave it the name “the Liberal-Democratic Party of Russia”, in order to discredit in the minds of the people the terms “liberal” and “democratic”. It worked. [9]

So a proud, non-democratic Russia not only suits Putin and his cronies who can cream off the country’s wealth to ensure that they remain in power and that they enjoy all the material benefits this can bring; it also suits many Russian people, especially if they can be kept in ignorance of the extent of corruption at the top and transfixed in the belief that the West is in chaos and wanting to destroy Russia to save itself. Rather like Russia’s two-headed eagle, the Kremlin’s disinformation machine looks two ways: in one direction, to disrupt the West; and in the other to keep the Russian people in a state of ignorance and fear of the supposed enemy.

Fig.8 Disinformation for the Russian people. Even before the collapse of the USSR, calling the extremist party of Vladimir Zhirinovsky “Liberal Democratic” discredited these concepts for many.

Source checking

Checking the sources of your information may sound obvious; but very few of us do it. Perhaps more accurately, most of us think that we check our sources, or at least use reliable ones. We tend to choose certain websites, broadcasters or newspapers because we trust them or because they reflect our (usually political) views. For example, in the UK someone who chooses to read the Daily Telegraph probably votes Conservative; readers of The Guardian can be expected to have sympathies for the Labour Party or the Liberal Democrats. Many Britons of all political shades consider that the BBC gives a balanced view of events, be it on television, radio or online (while some on the right and some on the left continually accuse the Corporation of bias one way or the other).

But in an age of fast-moving social media, people are exposed to sources they have never come across before and may not consciously choose to access. Receiving information from someone you follow on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter may take you to somewhere new; and if you are curious about this site, you may follow links from it to other unknown sites. If you discover something interesting – possibly shocking – but plausible, the reaction may be simply to pass it on to your friends and followers, without checking the authenticity of either the information or the source. As we shall see, this is fertile ground for the spreading of disinformation, which often becomes more believable the more it is spread – with or without critical comment.

The logical thing to do when faced with information from an unknown source is to check whether the source is reliable; but the pace of modern life means that we do that all too rarely. One estimate says that mankind produced more data in 2016 than in the whole of history before that; this in itself is a frightening thought.

A simple rule regarding sources should be similar to one we subconsciously apply to people whom we meet: if an introduction comes through someone we know and trust, we tend to believe their judgement that this person is to be trusted. So if someone in whom you have faith sends you a link to a site, check with them that they know the site and believe it can be trusted.

Beyond that, we can take other measures. Some very sound advice is listed on the “Who is Hosting This?” website.[10] Pointing out that there are over 600 million active websites in the world, Who is Hosting This? notes that, “Website owners can print anything they want, true or not, without worrying about the consequences.” So it is up to the individual to check whether what they are reading is true. One of the first things to check is the date of the article. If it is a few years old, it may be accurate but the information may no longer be relevant for a contemporary assessment of the subject under discussion. Another way to check the relevance is to see whether the references in the article still work; if a number of the links no longer work, you are probably looking at out-of-date, or possibly false, information.

Check the author, too. There are an awful lot of charlatans out there. A common trick employed by RT (the former Russia Today television channel and website) is to put someone up as a “specialist”, when they are nothing of the sort. One such person is Karen Hudes, who is described as a “World Bank whistleblower”. The World Bank issued a statement on its website in 2014 saying that, Karen Hudes has not been employed by the World Bank since 2007 and is in no capacity authorized to represent any arm of the World Bank Group. Any claims otherwise by Ms. Hudes or her proxies are false and should not be viewed as credible.[11]

RT ignores this, as it does her extraordinary belief that an alien race called homo capensis has secretly been waging war on humans for thousands of years, establishing different religions to divide mankind as well as manipulating our financial system. She claims that homo capensis, have very large heads, which is why Vatican officials (some of whom Hudes says are aliens) wear very large ceremonial hats.

A British so-called “expert” who frequently appears on RT is Tony Gosling. Although he is described as “an historian”, he has never taught history nor written any books about it. In fact, his views on history are driven by a conspiracy theory which holds that a secret society within the Freemasons, called the Illuminati (which briefly existed in Bavaria in the late 18th century) controls many world events today. His views were exposed in 2015 in an article by Adam Holland on “The Daily Beast” website, Russia Today Has an Illuminati Correspondent. Really [12]

Fig.9 Illustration for the article on The Daily Beast website, Russia Today Has an Illuminati Correspondent. Really.

Another way of checking the reliability of a web source is by looking at the domain name and the Top Level Domain (TLD): .com, .co.uk, .gov and so on. If the TLD is .gov, it is a government website, so the information contained on it will be official. Many TLDs refer to a country.13 However, the .com TLD is used by any number of firms in any number of countries, and whilst it may be safe it may also promote a particular brand. Any of the more obscure 700 or so TLDs, though, should be regarded with deep suspicion.

If in doubt about the reliability of a site, it is worth looking at other stories on that site to see whether they can be stood up. And it is always worth checking the grammar and the spelling. The odd typo can be excused. But a large number of mistakes suggests unreliability. When going further into research, it is wise to follow guidelines issued by academic institutions, such as Columbia College in the USA.[13] Columbia’s website gives five basic guidelines:

- Where was the source published?

- Who wrote it?

- Is the piece timely and appropriate for its field?

- For whom is the source written?

- Will you use the source as a primary or secondary text?

Each of these is explained in more detail on the site.

Fact checking

As important as checking your sources, before you quote any facts or figures it is good sense to check any facts which you want to cite in written or oral testimony, especially if these are statistics. A “fact” which proves to be false may well turn out to be an example of misinformation rather than disinformation; but by repeating it, it may mean that you lose credibility because of a mistake. If challenging a supposed fact in public, you must be absolutely sure that you are right, particularly if your interlocutor turns aggressive. Ideally, try to prove your position on the spot. If this proves impossible, do follow up. This can also prove to be a useful method for finding out whether the original source of the information is genuine or not. As a general rule, a propagandist will never acknowledge a mistake. In particular, if they cover up the false information by ignoring your claim and trying instead to make a comparison with someone else (“What about X?”) they are almost certainly lying. [14] 13 Only one country does not have its name as a TLD: the USA, as the founder country of the worldwide web. This is the modern version of the postage stamp. The only country which does not have its name on postage stamps is Britain, as it was the first country to issue stamps and thus did not need to say from where they came.

Images

“Every picture tells a story”; but is it the story you think it is? Russian purveyors of disinformation, be it RT, Sputnik, websites or social media, have consistently used images which are completely unrelated to the issue they are discussing, or have been photo-shopped to change the meaning, to try to win people over to their way of thinking. Just two out of hundreds of such falsely used images are shown at Fig.10 and Fig.11. Many more examples of fake photographs, wrongly-captioned photographs and vicious Russian anti-Western propaganda can be found on Julie Davis’ various websites, all accessed via www.russialies.com.

Fig.10 Especially in the first few months of the war which Russia unleashed on Ukraine in 2014, images such as this were widely used. The version on the left is a screenshot from the Rossiya TV channel news programme, Vesti, bearing the caption, “Donetsk Region, Ukraine”. The original, uncovered by Julie Davis, showed that the photo was in fact taken some years earlier, in a conflict in the Kabardino-Balkaria Region of the Russian Federation.

Fig.11 Another fake uncovered by Julie Davis. Russian trolls photo-shopped the genuine photo on the right-hand side of a young Ukrainian girl in order to change completely her appeal for the war to stop in the East of her country – the war which the Russians started in 2014.

Fig.11 Another fake uncovered by Julie Davis. Russian trolls photo-shopped the genuine photo on the right-hand side of a young Ukrainian girl in order to change completely her appeal for the war to stop in the East of her country – the war which the Russians started in 2014.

Examples: MH17; Syrian Chemical Attacks; Skripal Affair

There is no shortage of examples of the Russian use of disinformation to try to confuse people in the West and persuade their own people that in every case the Russian state is innocent of any wrongdoing while the West is always to blame. Three particularly vivid examples are:

- the shooting-down of the Malaysian airliner, MH17, over Ukraine in July 2014

- attacks using chemical weapons by Syrian government forces, such as the one on the village of Khan Sheikhoun on 4 April 2017

- the poisoning of the former Russian double agent, Sergei Skripal, and his daughter, Yuliya, in Salisbury, England, on 4 March 2018.

MH17

On 17 July 2014, a Malaysian airliner, flight MH17, was shot down by a Russian-made BUK surface-to-air missile while flying over territory in Eastern Ukraine occupied by Russian forces since the invasion four months earlier. Immediately the ‘plane was hit, tweets were posted by either Russian soldiers or Russian-backed Ukrainians boasting that they had shot down a Ukrainian Air Force transport aircraft. When the remains of the airliner fell to earth and they realised that it was a civilian airliner, the tweets were deleted.

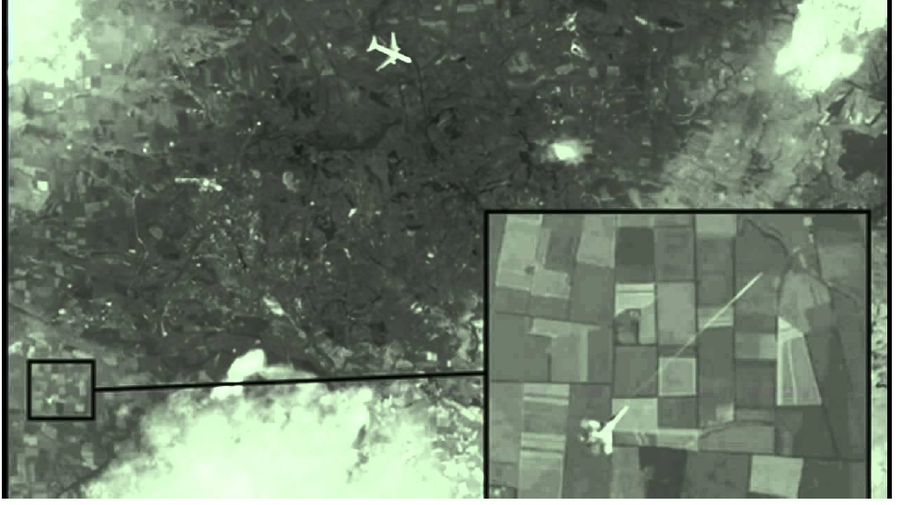

Four days later, the Russian Defence Ministry held a press conference to start the disinformation process. At this press conference and in subsequent messages from the Kremlin, contradictory versions flowed from the Russian disinformation machine.[15] It was claimed that MH17 was shot down by a Ukrainian SU-25 jet fighter (ignoring the fact that an SU-25 carrying missiles cannot fly above 25,000 feet, when the airliner was at 33,000 feet, as is usual for passenger aircraft); there was a bomb on board, as the remains “clearly showed” (the remains clearly showed that the explosion had been outside the aircraft); the Ukrainian Air Force mistook the airliner for a ‘plane in which they believed Vladimir Putin was travelling; it was a Ukrainian BUK which shot it down. One of the most absurd “explanations” was the publication of a satellite photograph supposedly “showing a Ukrainian jet firing at the airliner” – had the photo-shopped image been genuine, the airliner would have been four miles across! (Fig.12)

Fig.12 The Russian “satellite photo” which purported to show the shooting down of MH17 by a Ukrainian jet fighter. Analysis of the photo showed that the airliner would have been four miles across if the photo were genuine.

It shows the brazen nature of Russian disinformation that the Kremlin didn’t care that these versions were contradictory or simply nonsensical. What they succeeded in doing was convincing many Russians that the West was out to attack Russia; and many Westerners that the situation was so confused that it was better not to believe any version rather than blame Russia. Bellingcat’s later detailed investigation, which proved beyond doubt that it was a Russian BUK missile which shot down MH17 was simply ignored by many.

The Khan Sheikhoun chemical attack in Syria, April 2017

On 4 April 2017, Su-22 jet aircraft of the Syrian Air Force attacked the village of Khan Sheikhoun. The Syrian government and their Russian allies later claimed that they were attacking a chemical weapons storage facility held by anti-government Syrian rebels, although at no time did they suggest how the rebels had got hold of chemical weapons. In fact, as Bellingcat proved once again, after painstaking and thorough research, the Syrian Su-22s dropped chemical shells.[16] As with the shooting down of MH17, once again the Russian disinformation machine went into action, asserting not only that the chemical was on the ground and not fired from the jets, but even claiming that the raid took place at a different time from that stated by those on the ground.

Fig.13 The crater in the road in Khan Sheikoun where a chemical shell exploded on 4 April 2017. Detailed investigations proved that the Syrian Air Force had carried out an attack using chemical weapons, despite the denials of Russia and the Syrian regime.

Witnesses on the ground all said that the attack took place around half past six in the morning, whereas the Russian version said it was around eleven o’clock. To be effective, the attack had to take place in the early morning, so that the chemical would spread at ground level. Had the attack happened in the heat of the day (at 11 o’clock, for example) the chemical would have been dispersed much quicker by the heat of the sun. Open-source intelligence which tracked the aircraft showed that the jets had flown early in the morning.

As a result of this air-raid, President Donald Trump ordered an attack on the Syrian air base from which the Su-22s had flown. The air base was supposedly protected by Russian anti-missile missiles. Russian TV later claimed that their defensive shield had succeeded in knocking out around half of the US missiles. This was a lie. The Russian missiles failed. All of the US missiles reached their targets.

The Skripal Affair, March 2018

On 4 March 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian double agent now living in the UK, and his daughter, Yuliya, were found in a comatose state on a bench in the quiet provincial English city of Salisbury. It was swiftly determined that they had been attacked using a nerve agent. A policeman who investigated the case also ended up in hospital with poisoning from a nerve agent.

Fig.14 Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yuliya. The photo of Sergei was taken when he was on trial in 2006 for espionage against the Russian state. Russian defendants are frequently kept in a cage in the courtroom, hence the bars in the photo. Skripal was sentenced to 13 years in prison, but as part of a spy swap he was freed in 2010 and left Russia for the UK.

Twelve years earlier, on 1 November 2006, an ex-KGB agent, Alexander Litvinenko, had been poisoned in London by a rare radioactive substance, polonium. The polonium trail led, quite literally, back to Moscow. Traces of polonium were found everywhere the two Russians whom Litvinenko had met that day had been: on the seats on the aircraft on which they flew to London; in the hotel where they stayed; even at the Emirates Stadium where, having done what they came for, they calmly went to see the Russian football team, CSKA Moscow, play Arsenal in a European Champions League match. The Kremlin’s guilt was there for all to see.

Nevertheless, Moscow denied any involvement; just as they were to do in 2018 over the attack on the Skripals. With the Skripals, though, disinformation kicked in on a scale never seen before. Even before the British Prime Minister, Theresa May, had accused Russia publicly of being responsible for the attack, the Kremlin – both through its spokespeople and the media it controls – had already come out with seven different versions as to who was responsible. The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) confirmed that the nerve agent which was used was something which only a state could produce, and agreed with the findings of the British government that Russia was the source. Needless to say, despite this Russia denied having anything to do with the attack.

Over the weeks which followed, the Kremlin came out with more than 20 further accounts of who was responsible, even – absurdly – claiming that it was the future mother-in-law of Yuliya Skripal who was responsible for the attack.

But unlike the Litvinenko affair, this time the international community agreed with the assessment of the UK government that Russia was responsible. Almost 30 countries joined the UK in expelling Russian diplomats. The USA alone expelled 60 Russians, and then introduced some of the toughest sanctions yet against the Kremlin and those close to it. This led to a major drop in the value of shares in Russian companies and a crisis on the Moscow Stock Exchange. Perhaps the world had at last woken up to the threat Russian behaviour was causing.

Methodology: How best to deal with disinformation

When setting out to debunk or disprove disinformation it is very easy to fall into the trap of treating it as an exercise in logic. Disinformation is not a matter of logic. It relies on emotion; scepticism; and the goodwill of naïve people or useful idiots, or the evil intentions of fellow travellers.

If there were any logic to disinformation, putting out five contradictory versions of the shooting-down of MH17, or 30 different versions of the Skripal affair would make no sense. The Kremlin knows, too, that the majority of people at whom these different versions are aimed will not stop to compare the sources; or if they do they will say that they are different sources – “a Russian newspaper says this, while the Ministry of Foreign Affairs says that” – not realising that the source is actually the same.

But if disinformation relies on provoking an emotional response, countering it means putting emotion to one side and explaining clearly, concisely and rationally why what is being pushed is not true. The images at Fig.11 above are perfect examples of this. A picture of a young child holding a sign saying “I want war” automatically provokes the emotional human response, “How awful! Who are the evil people engendering such hatred in children?” But showing that the real photo, of the child holding a sign which reads, “I don’t want war”, and demonstrating that this photo was published first, graphically illustrates the threat posed by the disinformers and should make any thinking person aware of the danger.

Even with such vivid examples of disinformation, though, there is still a mighty obstacle for people brought up in liberal, Western societies to overcome: the fact that the head of a huge and important country such as Russia can look you in the eye (or directly into a television camera) and tell lie after lie after lie. Yes, most people accept that politicians of any shade in any country don’t always tell the truth or the whole truth, for a variety of reasons. At one end of the scale it may be to try to improve their own – or their political party’s – image. At the other, it may be because to tell the whole truth could reveal secrets which may pose a threat to national security. But in Western democracies politicians do not repeatedly lie, as they will be eventually found out, thanks to a free press.

Vladimir Putin can lie constantly because there is no free press in Russia which will hold him to account; he has made sure of that. Nothing intimidates journalists more than physically attacking, or even worse killing their prominent colleagues who dare to criticise the regime openly. Anna Politkovskaya’s assassination in 2006 sent a powerful signal to any would-be investigative journalist in Russia that the Putin regime has no qualms about removing annoying journalists. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, this was only one of 58 murders of journalists in Russia between 1992 and 2018.[17]

Fig.15 Western cartoons of Putin’s relationship with the Russia media are not as funny as they may seem.

A fair question which should be asked by anyone is, why does Putin lie? This comes down to the two basic factors discussed in section 2 above: wealth and power. Putin and those in his immediate circle made themselves wealthy by creaming off the assets of the state in the 1990s. Putin then put himself in a position to seize power from the ailing Boris Yeltsin in 1999, by guaranteeing Yeltsin protection from prosecution for the rest of his life when he stepped down as President in favour of Putin. Rarely can the phrase “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely”,[18] have been more vividly demonstrated in practice than Putin’s rise to power and subsequent behaviour in power. In order to maintain his wealth and power (and that of those around him), Putin has fallen back on a centuries-old suspicion of the West inherent in many Russians to persuade his own people that the West is a threat, and to sow in Western people a mistrust of their own institutions. Even in the age of the internet and social media, Putin’s control over information in his own country, and manipulation of information by using the West’s freedom of speech against itself has seen him register notable victories among both audiences.

It is vital to understand the reasons behind Putin’s warped reasoning – the fact that he is prepared to lie and to kill to protect his wealth and power – if we are to comprehend why the Kremlin has launched this information attack on the West. Only then can we begin to combat it. In Soviet times there was an ideological element, the battle of Capitalism versus Communism. That no longer plays a part. But Putin wants the West at least to respect Russia; better still to fear Russia. That is Putin’s mindset. If in Soviet times the leadership of the USSR relied on Western sympathisers with the Communist cause to help them in their mission, nowadays the Kremlin can call upon support in the West from three groups of people: naïve Russophiles who, despite all the evidence to the contrary, believe that Putin “can’t be all that bad, and anyway the Americans are just as bad”; those who are prepared to toe the Russian line in return for money; or those who are being blackmailed.

When dealing with disinformation it is necessary not only to discredit the lies which the Kremlin issues, but those which are repeated and sometimes exaggerated by Putin’s sympathisers in the West. It would be pointless – and indeed impossible, because of the number of lies the Kremlin issues – to try to counter every piece of disinformation which Russia puts out. It is far better to concentrate on the most obviously absurd examples.

So, difficult though it is to put aside emotions over the fact that 298 innocent people perished when the MH17 airliner was shot down over occupied Ukraine in July 2014 and simply get into a “did-didn’t-did-didn’t” argument with the Russians over who was to blame, it is far more effective to point out (as above) that it is physically impossible for an SU-25 jet which cannot fly above 25,000 feet to shoot down an airliner flying at 33,000 feet; to point out that the “bomb on board” theory is swiftly disproved by the wreckage of the ‘plane, which clearly shows that the explosion came from outside the aircraft (a BUK missile doesn’t have to hit the target; it is enough to explode close to it to take a ‘plane out of the sky); and to show that simple investigation of the supposed “satellite image” would show that the airliner would have had to be four miles wide for the picture to be genuine!

The whole idea of the Kremlin issuing multiple “explanations” for its crimes, such as for MH17 or in the case of the poisoning of Sergei and Yuliya Skripal, with its 30 or so different versions of what happened is also in and of its very nature damning. Remembering that there is no free press in Russia, and that therefore anything broadcast on television or published in a newspaper has been officially approved, all of these versions come from one source. But if you are telling the truth, you need only one version: the truth.

It is important to be selective in debunking disinformation also because studies have shown that repeating the lie – even to disprove it – can actually strengthen it; and that giving too many examples can confuse the audience, sending them back to the original lie as a possible version of the truth. [19]

One very effective way of dealing with disinformation can be to ridicule it. Pointing out that the airliner in Fig.12 (above) would have been four miles across if this were a genuine satellite photo is one example. Of the multiple lies told about the Skripal case, it is effective to point out the absurdity of the version which claimed that it was Yuliya Skripal’s would-be future mother-in-law who had used the Novichok chemical against the Skripals, because she did not want her son to marry Yuliya. If your future mother-in-law has access to chemical weapons, you’re in the wrong relationship!

When you explain, calmly and rationally, that the Kremlin is lying so blatantly and absurdly in such cases, it is easier to illustrate that there is a pattern to such lies.

Another point to bear in mind when discrediting disinformation is to look for obvious signs which give the game away. Just as in the world of intelligence gathering it can be the simplest route which gives an answer, so the most straightforward approach can reap rewards with disinformation.

To quote an intelligence example: in the 1980s, a new tank appeared in the Soviet Army and the armies of the Warsaw Pact countries. Western intelligence was intrigued to find out its designation. Every year the East German Army (the Nationale Volksarmee or NVA) marked the country’s national day on 7 October with a parade in East Berlin. For three nights before the parade rehearsals were held in the city. British, American and French military personnel had the right to travel into East Berlin at any time, under the terms of the post-War division of the city, and intelligence officers and soldiers would use this opportunity to try to see the Warsaw Pact equipment up close. The East German soldiers were, of course, told to avoid any fraternization with the NATO “enemy”. But soldiers always have a common language, and one enterprising

German-speaking British corporal offered an NVA soldier a cigarette and in the course of conversation calmly asked him what they called the new tank. “Oh, we call this the T-80”, replied the German. One up for simple, human intelligence.

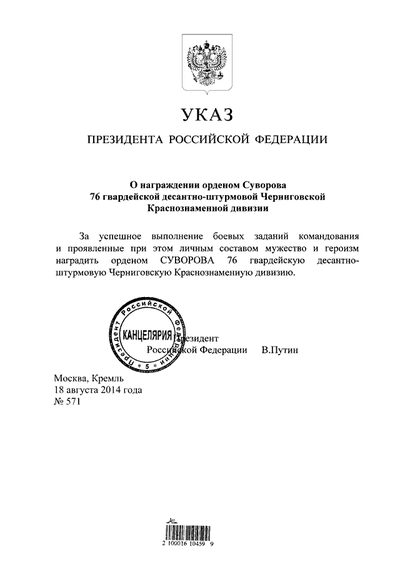

Modern social media has made this task simpler in some ways. While the Kremlin denies that there are any Russian soldiers fighting in Eastern Ukraine, Russian soldiers have sent tweets with selfies and messages such as, “Hi, Mum, here I am in Ukraine”.[20] And in the summer of 2014, when the Russian authorities were vehemently denying that they were fighting a war there, Putin issued a presidential decree granting the Order of Suvorov, one of Russia’s highest military awards, to the 76th Guards Parachute Chernigov Red Banner Division, “For the successful completion of their military tasks and for demonstrating courage and heroism”.[21] The only place where the Division could have been fighting to have earned the award was Ukraine. Around this time, too, some Russian journalists were beaten up for investigating the appearance of fresh military graves in the city of Pskov.[22]

When debunking disinformation, it is important to keep in mind that you will never convince all of the people all of the time; and that whatever evidence you present to some people they would still rather believe in conspiracy theories than carefully-reasoned facts. There is little point in trying to debunk disinformation to those who claim that the Moon landings never happened; that Princess Diana is living in luxury on a remote island somewhere; or that the Malaysian airliner MH370, which disappeared over the Indian Ocean in March 2014, was abducted by aliens. You will receive the response, “Ah, well you would say that, wouldn’t you?” It is more important to concentrate efforts on policy-makers and the mass of the population who believe that protecting the security and freedoms of the Western world is something worth standing up for.

References

- ↑ One word which is not a synonym for “disinformation”, though, is “misinformation”, although many commentators wrongly use the two words interchangeably. Disinformation is deliberately passing on false information in order to confuse or mislead the recipient. Misinformation is mistakenly passing on wrong information, without intending to mislead.

- ↑ This is not dissimilar from the UK system of Parliamentary Elections. If an elector votes for a party which does not win in his or her constituency, their vote counts for nothing. A party can gain more votes but still have fewer seats in parliament than another.

- ↑ Interfax: Shoigu: Information becomes another armed forces component 28/03/2017. See http://www.interfax.com/newsinf.asp?id=581851

- ↑ The word “disinformation” is a rare example of a word which has come into English (and other languages) from Russian. The Russian language adopted the term from the Latin, informatio, creating информация (informatsiya). Russian added the prefix “dez” to create дезинформация (dezinformatsiya), which has come into English as “disinformation”.

- ↑ A summary of propaganda methods in World War One can be found at https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/propaganda-as-a-weapon

- ↑ For example, at a conference in Moscow on 28 January 2015, Major-General (Retired) Alexander Vladimirov, started his presentation with the words, “Russia finds itself in a war for its very survival as an Orthodox civilisation, a “super-ethnos” and a great state”.

- ↑ For a detailed description of the plot to blow up the apartment blocks see Alexander Litvinenko and Yuri Felshtinsky, Blowing Up Russia: Terror from Within (Encounter Books, 2002). Accounts of the brutality of the second Chechen war can be found in the writings of Anna Politkovskaya, who was murdered in Moscow on 7 October 2006. Among English language sources, for example, see Anna Politkovskaya, Nothing But the Truth (Vintage Books, London, 2011).

- ↑ This was a huge psychological blow, greater than the British recognition that it was no longer the head of the world’s largest empire, especially as that was a process spread over a number of years.

- ↑ The Liberal-Democratic Party of Russia was the first political party to be registered after the Communist Party gave up its monopoly of power, even before the Communist Party itself registered.

- ↑ http://www.whoishostingthis.com/resources/credible-sources/

- ↑ See http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2014/07/08/statement-former-staff-karen-hudes

- ↑ http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/07/08/russia-today-has-an-illuminati-correspondent-really?via=mobile&source=twitter Gosling even went so far as to say on RT that the G7 Summit in 2015 took place in Bavaria because it was convenient for the Bavarian Illuminati.

- ↑ See https://www.college.columbia.edu/academics/integrity-sourcecredibility

- ↑ This practice has come to be known as “whataboutism” and is a common Russian trick to cover up disinformation or create new areas of it.

- ↑ For a summary of Moscow’s constantly changing and contradictory narrative, see https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2018/01/05/kremlins-shifting-self-contradicting-narratives-mh17/. Bellingcat has carried out detailed, thorough and conclusive research to debunk many examples of Russian disinformation

- ↑ See https://www.bellingcat.com/news/mena/2017/04/10/khan-sheikhoun-chemical-attack-bombed/ for a full account of the Bellingcat research.

- ↑ 18 See https://cpj.org/europe/russia/ for a year-by-year breakdown of the murder of Russian journalists.

- ↑ As Lord Acton (John Dalberg-Acton) wrote in a letter to Bishop Mandell Creighton on 5 April 1887 and has been said many times since.

- ↑ An excellent summary of why too much counter-information can play into the hands of the disinformers is given in The Debunking Handbook by John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky, which can be downloaded from here: https://www.skepticalscience.com/docs/Debunking_Handbook.pdf.

- ↑ Vice News made a 23-minute film in 2015 in which their correspondent, Simon Ostrovsky, tracked a journey made by a Russian soldier, Bato Dambaev, from the Far East to Ukraine, all of which had been revealed by his social media profile. The film can be seen at https://www.vox.com/2015/6/17/8795235/russia-ukraine-troops, along with an article, Russia is invading Ukraine. How do we know? Russian troops’ selfies, among other things.

- ↑ The decree was published on the website of the Russian President: http://kremlin.ru/acts/news/46469.

- ↑ See the BBC report quoting journalists from the local newspaper, Pskovskaya Guberniya: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-28949582.