2008 Counter-Terrorism advertising campaign

Template:Counter-Terrorism Portal badge <youtube size="small" align="right" caption="Audio Recording of Banned Radio Advert that appeared on Talksport. Retrieved on 12 August 2010">lQubNQ5-ULc</Youtube>

In 2008, the Metropolitan Police and the police forces of Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire and the West Midlands launched a five-week poster and radio campaign to get members of the public to report any “suspicious behaviour” they may have encountered in their daily lives to the Anti-Terrorist Hotline. The slogans of the campaign were – “if you suspect it, report it” and “Terrorists won’t succeed if someone reports suspicious activity – you are that somebody”.[1]

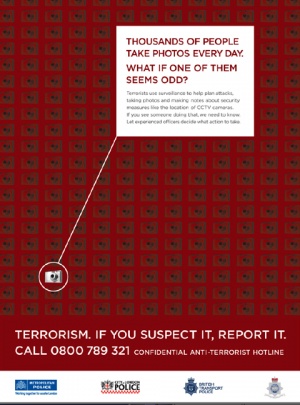

The campaign became known for its poster campaign, which had simplistic and wide-sweeping slogans such as:[2]

- “Thousands of people have mobiles. What if someone with several seems suspicious?”

- “You see hundreds of houses every day. What if one has unusual activity and seems suspicious?”

- “Thousands of people take pictures every day. What if one of them seems odd?”

Contents

Police Rationale for Campaign

The rationale behind the poster campaign was explained by the lead-agency that devised the campaign, the Metropolitan Police, who suggested that the campaign was crucial because even though the public of London was aware of terrorism issues , they lacked “alertness”. When Londoners thought about terrorism, they thought of “’bombs on tube/bus’, ‘man with rucksack’ because of past events. Their minds jump straight to the point of attack and therefore what they do not necessarily consider are the planning stages leading up to an attack.” The purpose of the campaign was to inform the public that rather than the actual attack, information was required about its preparation stages. Therefore, the campaign aimed to alert the public of the “community setting eg. home, local area, place of work etc...” [3]

Objectives of Campaign

Operational Objectives

- Collate "actionable information" to minimise the risk from terrorism

- To "reassure" the public that the Metropolitan Police and other police forces are working hard to combat terrorism

- To ensure that people who reside in vulnerable areas understand what constitutes suspicious activity and understand the avenues to report such suspicions - ie., the Anti-Terrorist Hotline.[3]

Direct Objectives

- Raise awareness, and trust, in Anti-Terrorist Hotline

- Encourage people to report "suspicious" activity

- Educate people what constitutes "suspicious activity"

- "Reinforce and remind" the public to remain "alert and vigilant" in the "fight against terrorism"

- To ensure the public understands that the Police is working hard to combat terrorism. [3]

Stakeholders in Campaign

According to the Metropolitan Police Service, the stakeholders in the poster campaign are: [3]

- Metropolitan Police Service and Metropolitan Police Authority

- The Home Office

- The Mayor's Office

- The Security Services - MI5 and MI6

- Emergency Services

- Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO)

- British Transport Police (BTP)

- City of London Police (CoLP

- Transport for London (TfL)

- Greater London Authority (GLA)

- MOD Police

Using the Media to Target the Campaign

Research into the poster and radio campaign indicated that the best time to target people with the adverts was in the evening because when people were going into work, they did not let the threat of terrorism "get in the way of going about their day ... [and] ... were therefore, less likely to engage with a counter-terrorism message when in this work-focussed ... mode." [3]

Research suggested that the best time to communicate the message of the campaign was when people were in a "home mode" and were on their way home to see "family and friends" because "people do not generally fear for themselves when thinking about terrorism" but fear for "those close to them" and therefore "by communicating our messages at a time when our audience are on their way home to see these people would make the communication resonate even more." [3]

This requirement led to key evening press titles and radio slots to be chosen for dissemination of the campaign. [3]

Another major benefit of the evening slot was that an ongoing high-profile terrorism court-case (Operation Crevice) was being reported by the media, which meant that "our advertising was integrated within relevant editorial which would have generated higher recall amongst readers".[3]

Radio stations were selected because "the nature of radio ... meant that specific days and dayparts could be upweighted [and this] enabled the communication to reach people during drive time, evenings and weekends, as well as more towards the end of the week rather than the beginning [of the week] when they [were] in “work mode”".

The Metropolitan Police Service also purchased "a long list of specific keywords on the top three online Search Engines (Google, MSN and Yahoo) to ensure that the counter-terrorism section of the Metropolitan Police Service site would appear at the top of the results page. [3]

Learnings from Campaign

These are the learnings from the campaign, according to the creators of the campaign - the Metropolitan Police Service: [3]

- There was no indication or evidence to suggest that people had moved from being "good citizens" to being "alert reporters". As a result, "there is much work to be done to encourage people to be vigilant and call the ATH with information.

- The radio campaign was most successful compared to any other mode of campaigning because "radio was able to cut through other advertising [modes and explain] the need for vigilance and trust of the ATH messages.

- Outside of London, the campaign was a success and has succeeded "in generating awareness of the issue and its relevance to all [people], not just Londoners."

- The campaign demonstrated that marketing has a role to play in providing people with not only information, but also [an] ability to positively affect people’s perceptions [and judgements] in regards to policing and safety."

No. of Calls Resulting from Campaign

During the campaign, there was a significant rise in calls regarding suspicious activity to the Anti-Terrorist Hotline in 2007. The results were:[3]

- January: 318 calls

- February: 280 calls

- March: 681 calls

- April: 346 calls

Internet Website Hits

The new Anti-Terrorist Hotline pages on the Metropolitan Police Service website had 2,101 hits in March 2007. This increased to 11,306 in April 2007.[3]

The Greater Manchester Police website registered 328 visitors in March 2007 to its relevant Counter-terrorism pages. For April 2007, when the campaign was no longer running, it decreased to 112 visitors.

There was also a slight increase in the number of visitors to the West Yorkshire and West Midlands CT pages.[3]

Counter-Terrorism Radio-Advert Banned

In August 2010, a radio advert created by the Association of Chief Police Officers promoting the confidential Anti-Terrorist Hotline was banned by the Advertising Standards Agency under "Section 2, Rule 9 of the (Broadcast) Radio Advertising Standards Code (Good taste, decency and offence to public feeling)".[4]

It appeared on the Talksport radio channel,[5] in which a man can be heard saying:

- "The man at the end of the street doesn't talk much because he likes to keep himself to himself. He pays with cash because he doesn't have a bank card, and he keeps his curtains closed because his house is on a bus route. This may mean nothing, but together it could all add up to you having suspicions. We all have a role to play in combating terrorism. If you see anything suspicious, call the confidential Anti-Terrorist Hotline on 0800 xxxxxx. If you suspect it, report it".[6]

The advert was banned after 18 official complaints were made to the Advertising Standards Agency (ASA).

- 10 listeners believed that the add encouraged people to suspect and report law-abiding citizens to the police and thus found it offensive (This decision was upheld)

- 16 listeners believed that the ad "encouraged people to harass or victimise their neighbours" and was therefore "harmful" (this was not upheld)

- 9 listeners believed that the advert played on the public's "fear" (this offence was not upheld).[4]

In describing why it was banned, the ASA suggested it "could ... describe the behaviour of a number of law-abiding people within a community and we considered that some listeners, who might identify with the behaviours referred to in the ad, could find the implication that their behaviour was suspicious [and] offensive ... We therefore concluded that the ad could cause serious offence." [4]

The ASA ruled that "The ad must not appear again in its current form."[4]

Police Response

The Metropolitan Police Service - responding on behalf of ACPO - defended the campaign by suggesting that the purpose of the campaign was to inform the public that "[w]hat sometimes appeared to be insignificant behaviour could be linked to terrorist activity".[4] They continued: "[the] advert aimed to ask the public to trust their instincts and report anyone or anything that they believed was suspicious to specially trained police officers".[4]

Criticisms of Campaign

The anti-terror campaign has led to some serious criticism for the police services, who, it has been argued, were, through their adverts, exaggerating the threat and encouraging people in their everyday lives to spy on their neighbours and fellow citizens without any justifiable reason.

Critics have also argued that the entire campaign is aimed at the wrong people and that “raising awareness of the threat will only increase the fear and stress of the daily commute. If we must have an advertising campaign, maybe it is time to bring back the 'Keep calm and carry on' posters from retirement."[7]

In response to the poster campaign, many people have manipulated the posters to show their wide-sweeping remit and ambiguity. Notable examples include slogans such as:[8]

- "A bomb won't go off here because years before George Bush invaded Iraq."

- "Last week a man idly wondered: are these cameras really protecting my liberty, or infringing it? He's dead now."

Notes

- ↑ 2006 Metropolitan Police Counter-Terrorism Advertising Campaign Launched Metropolitan Police, accessed 23 Nov 2009

- ↑ 2008 Counter-Terrorism Advertising Campaign Launched, Metropolitan Police website, accessed 23 Nov 2009

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m See Appendix 1, MPS response to the MPA report 'Counter Terrorism: the London Debate', ‘‘Metropolitan Police Authority’’, Report 9, 28 June 2007, produced by the Commissioner, accessed 13.08.10

- ↑ a b c d e f ASA Adjudication on The Association of Chief Police Officers, Advertising Standards Agency, 11 August 2010, accessed 11.10.08

- ↑ Anti-terrorist hotline ad banned for being 'offensive', BBC News, 11 August 2010, accessed 11.08.10

- ↑ Banned Anti Terrorism Hotline Radio Advert, Youtube, accessed 11.08.10

- ↑ Jeremy Kuper, Join the Snooper Troopers, Comment is Free, 6 April 2009

- ↑ Remixes of the Paranoid London Police anti-terror/suspect your neighbours posters accessed - 23 November 2009