Difference between revisions of "SEATO"

m (Text replacement - "|twitter= " to "") |

(unstub) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SEATO | |wikipedia=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SEATO | ||

|spartacus=http://spartacus-educational.com/USAseato.htm | |spartacus=http://spartacus-educational.com/USAseato.htm | ||

| − | |start= | + | |start=1954 |

| + | |logo=Flag of SEATO.png | ||

|headquarters=Bangkok, Thailand | |headquarters=Bangkok, Thailand | ||

| + | |interests=George F. Kennan,Truman doctrine | ||

|type=intergovernmental military alliance | |type=intergovernmental military alliance | ||

|abbreviation=SEATO | |abbreviation=SEATO | ||

| + | |description=1950s attempt to replicate [[NATO]] in Asia. | ||

}} | }} | ||

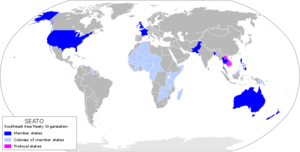

| + | [[image:Map of SEATO member countries - en.png|thumbnail|Map of SEATO members, shown in blue.]] | ||

| + | The '''Southeast Asia Treaty Organization''' ('''SEATO''') was an [[international organization]] for [[collective security|collective defense]] in [[Southeast Asia]] created by the '''Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty''', or '''Manila Pact''', signed in September 1954. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Primarily created to block further [[communism|communist]] gains in Southeast Asia, SEATO is generally considered a failure because internal conflict and dispute hindered general use of the SEATO military. SEATO was dissolved on 30 June 1977 after many members lost interest and withdrew. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though Secretary of State Dulles considered SEATO an essential element in U.S. foreign policy in Asia, historians have considered the Manila Pact a failure, and the pact is rarely mentioned in history books.<ref>Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization page 1</ref> In ''The Geneva Conference of 1954 on Indochina'', Sir [[James Cable]], a diplomat and naval strategist,<ref>https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1359279/Sir-James-Cable.html </ref> described SEATO as "a fig leaf for the nakedness of American policy", citing the Manila Pact as a "zoo of [[paper tiger]]s".<ref>Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization page 1</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Origins and structure== | ||

| + | The Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, was signed on 8 September 1954 in [[Manila]],<ref>Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization page 1</ref> as part of the American [[Truman Doctrine]] of creating anti-communist bilateral and collective defense treaties.<ref>Jillson, Cal (2009). American Government: Political Development and Institutional Change p=439}}</ref> These treaties and agreements were intended to create alliances that would keep communist powers in check ([[China|Communist China]], in SEATO's case).<ref>Ooi, Keat Gin, ed. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, From Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO pp=338–339</ref> This policy was considered to have been largely developed by American diplomat and Soviet expert [[George F. Kennan]]. President [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]]'s Secretary of State [[John Foster Dulles]] (1953–1959) is considered to be the primary force behind the creation of SEATO, which expanded the concept of anti-communist collective defense to Southeast Asia. Then-Vice President [[Richard Nixon]] advocated an Asian equivalent of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization ([[NATO]]) upon returning from his Asia trip of late 1953,<ref>''Nixon Alone'', by Ralph de Toledano, pp. 173–74</ref> and NATO was the model for the new organization, with the military forces of each member intended to be coordinated to provide for the collective defense of the member states. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Organizationally, SEATO was headed by the Secretary General, whose office was created in 1957 at a meeting in [[Canberra]],<ref>Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization. ProQuest. p=184</ref> with a council of representatives from member states and an international staff. Also present were committees for economics, security, and information. SEATO's first Secretary General was [[Pote Sarasin]], a Thai diplomat and politician who had served as Thailand's ambassador to the U.S. between 1952 and 1957, and as Prime Minister of Thailand from September 1957 to 1 January 1958.<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20110426162320/http://www.cabinet.thaigov.go.th/eng/pm_his.htm</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unlike the NATO alliance, SEATO had no joint commands with standing forces. In addition, SEATO's response protocol in the event of communism presenting a "common danger" to the member states was vague and ineffective, though membership in the SEATO alliance did provide a rationale for a large-scale U.S. military intervention in the region during the [[Vietnam War]] (1955–1975). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Consequently, questions of dissolving the organization arose. Pakistan withdrew in 1972, after East Pakistan seceded and became Bangladesh on 16 December 1971. France withdrew financial support in 1975, and the SEATO council agreed to the phasing out of the organization.<ref>https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=0lQ0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=YbkFAAAAIBAJ&pg=3661%2C2633318 </ref> After a final exercise on 20 February 1976, the organization was formally dissolved on 30 June 1977.<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20140502004607/http://www.almc.army.mil/ALU_INTERNAT/CountryNotes/PACOM/THAILAND.pdf</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Membership== | ||

| + | Despite its name, SEATO mostly included countries located outside of the region but with an interest either in the region or the organization itself. They were [[Australia]] (which administered [[Territory of Papua and New Guinea|Papua New Guinea]]), [[France]] (which had recently relinquished [[French Indochina]]), [[New Zealand]], [[Pakistan]] (including [[East Pakistan]], now [[Bangladesh]]), the [[Philippines]], [[Thailand]], the [[United Kingdom]] (which administered [[British Hong Kong|Hong Kong]], [[North Borneo]] and [[Crown Colony of Sarawak|Sarawak]]) and the [[United States]].<ref>Encyclopædia Britannica (India) 2000, p. 60</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Philippines and Thailand were the only [[Southeast Asia]]n countries that actually participated in the organization. They shared close ties with the United States, particularly the [[Philippines]], and they faced incipient communist insurgencies against their own governments.<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20121007113024/http://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/SEATO</ref> [[Thailand]] became a member upon the discovery of the newly founded "Thai Autonomous Region" (the [[Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture]]) in [[Yunnan]] (in South West China) – apparently feeling threatened by potential Chinese communist subversion on its land.<ref>US PSB, 1953 United States Psychological Studies Board (US PSB). (1953). US Psychological Strategy Based on Thailand, 14 September. Declassified Documents Reference System, 1994, 000556–000557, WH 120.</ref> Other regional countries like [[Post-independence Burma, 1948–62|Burma]] and [[Indonesia]] were far more mindful of domestic internal stability rather than any communist threat,<ref>https://web.archive.org/web/20121007113024/http://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/SEATO</ref> and thus rejected joining it.<ref>http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18430820 Nehru Has Alternative To SEATO. (5 August 1954). The Sydney Morning Herald (</ref> [[Federation of Malaya|Malaya]] (including [[Singapore]]) also chose not to participate formally, though it was kept updated with key developments due to its close relationship with the United Kingdom. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The states newly formed from French Indochina ([[North Vietnam]], [[South Vietnam]], [[Cambodia]] and [[Laos]]) were prevented from taking part in any international military alliance as a result of the [[Geneva Agreements]] signed 20 July of the same year concluding the end of the [[First Indochina War]].<ref>https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/seato</ref> However, with the lingering threat coming from communist [[North Vietnam]] and the possibility of the [[domino effect|domino theory]] with [[Indochina]] turning into a communist frontier, SEATO got these countries under its protection – an act that would be considered to be one of the main justifications for the U.S. involvement in the [[Vietnam War]]. [[Kingdom of Cambodia (1953–70)|Cambodia]], however rejected the protection in 1956.<ref>Grenville, John; Wasserstein, Bernard, eds. (2001). The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts. p 366</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The majority of SEATO members were not located in [[Southeast Asia]]. To Australia and New Zealand, SEATO was seen as a more satisfying organization than [[ANZUS]] – a collective defense organization with the U.S.<ref>W. Brands, Jr., Henry (May 1987). "From ANZUS to SEATO: United States Strategic Policy towards Australia and New Zealand, 1952–1954". The International History Review. No. 2. 9: 250–270</ref> The United Kingdom and France joined partly due to having long maintained colonies in the region, and partly due to concerns over developments in [[Indochina]]. Last but not least, the U.S. upon perceiving Southeast Asia to be a pivotal frontier for [[Cold War]] geopolitics saw the establishment of SEATO as essential to its [[Cold War]] [[Containment|containment policy]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All in all, the membership reflected a mid-1950s combination of anti-communist Western states and such states in Southeast Asia. The United Kingdom, France and the United States, the latter of which joined after the [[United States Senate|U.S. Senate]] ratified the treaty by an 82–1 vote,<ref>https://archive.org/details/vietnamfourameri0000unse p=46}}</ref> represented the strongest Western powers. [[Canada]] also considered joining, but decided against it in order to concentrate on its NATO responsibilities. | ||

| + | |||

{{SMWDocs}} | {{SMWDocs}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 06:09, 14 February 2021

| |

| Abbreviation | SEATO |

| Formation | 1954 |

| Headquarters | Bangkok, Thailand |

| Type | intergovernmental military alliance |

| Interests | George F. Kennan, Truman doctrine |

| 1950s attempt to replicate NATO in Asia. | |

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954.

Primarily created to block further communist gains in Southeast Asia, SEATO is generally considered a failure because internal conflict and dispute hindered general use of the SEATO military. SEATO was dissolved on 30 June 1977 after many members lost interest and withdrew.

Though Secretary of State Dulles considered SEATO an essential element in U.S. foreign policy in Asia, historians have considered the Manila Pact a failure, and the pact is rarely mentioned in history books.[1] In The Geneva Conference of 1954 on Indochina, Sir James Cable, a diplomat and naval strategist,[2] described SEATO as "a fig leaf for the nakedness of American policy", citing the Manila Pact as a "zoo of paper tigers".[3]

Origins and structure

The Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, was signed on 8 September 1954 in Manila,[4] as part of the American Truman Doctrine of creating anti-communist bilateral and collective defense treaties.[5] These treaties and agreements were intended to create alliances that would keep communist powers in check (Communist China, in SEATO's case).[6] This policy was considered to have been largely developed by American diplomat and Soviet expert George F. Kennan. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Secretary of State John Foster Dulles (1953–1959) is considered to be the primary force behind the creation of SEATO, which expanded the concept of anti-communist collective defense to Southeast Asia. Then-Vice President Richard Nixon advocated an Asian equivalent of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) upon returning from his Asia trip of late 1953,[7] and NATO was the model for the new organization, with the military forces of each member intended to be coordinated to provide for the collective defense of the member states.

Organizationally, SEATO was headed by the Secretary General, whose office was created in 1957 at a meeting in Canberra,[8] with a council of representatives from member states and an international staff. Also present were committees for economics, security, and information. SEATO's first Secretary General was Pote Sarasin, a Thai diplomat and politician who had served as Thailand's ambassador to the U.S. between 1952 and 1957, and as Prime Minister of Thailand from September 1957 to 1 January 1958.[9]

Unlike the NATO alliance, SEATO had no joint commands with standing forces. In addition, SEATO's response protocol in the event of communism presenting a "common danger" to the member states was vague and ineffective, though membership in the SEATO alliance did provide a rationale for a large-scale U.S. military intervention in the region during the Vietnam War (1955–1975).

Consequently, questions of dissolving the organization arose. Pakistan withdrew in 1972, after East Pakistan seceded and became Bangladesh on 16 December 1971. France withdrew financial support in 1975, and the SEATO council agreed to the phasing out of the organization.[10] After a final exercise on 20 February 1976, the organization was formally dissolved on 30 June 1977.[11]

Membership

Despite its name, SEATO mostly included countries located outside of the region but with an interest either in the region or the organization itself. They were Australia (which administered Papua New Guinea), France (which had recently relinquished French Indochina), New Zealand, Pakistan (including East Pakistan, now Bangladesh), the Philippines, Thailand, the United Kingdom (which administered Hong Kong, North Borneo and Sarawak) and the United States.[12]

The Philippines and Thailand were the only Southeast Asian countries that actually participated in the organization. They shared close ties with the United States, particularly the Philippines, and they faced incipient communist insurgencies against their own governments.[13] Thailand became a member upon the discovery of the newly founded "Thai Autonomous Region" (the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture) in Yunnan (in South West China) – apparently feeling threatened by potential Chinese communist subversion on its land.[14] Other regional countries like Burma and Indonesia were far more mindful of domestic internal stability rather than any communist threat,[15] and thus rejected joining it.[16] Malaya (including Singapore) also chose not to participate formally, though it was kept updated with key developments due to its close relationship with the United Kingdom.

The states newly formed from French Indochina (North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) were prevented from taking part in any international military alliance as a result of the Geneva Agreements signed 20 July of the same year concluding the end of the First Indochina War.[17] However, with the lingering threat coming from communist North Vietnam and the possibility of the domino theory with Indochina turning into a communist frontier, SEATO got these countries under its protection – an act that would be considered to be one of the main justifications for the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Cambodia, however rejected the protection in 1956.[18]

The majority of SEATO members were not located in Southeast Asia. To Australia and New Zealand, SEATO was seen as a more satisfying organization than ANZUS – a collective defense organization with the U.S.[19] The United Kingdom and France joined partly due to having long maintained colonies in the region, and partly due to concerns over developments in Indochina. Last but not least, the U.S. upon perceiving Southeast Asia to be a pivotal frontier for Cold War geopolitics saw the establishment of SEATO as essential to its Cold War containment policy.

All in all, the membership reflected a mid-1950s combination of anti-communist Western states and such states in Southeast Asia. The United Kingdom, France and the United States, the latter of which joined after the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty by an 82–1 vote,[20] represented the strongest Western powers. Canada also considered joining, but decided against it in order to concentrate on its NATO responsibilities.

References

- ↑ Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization page 1

- ↑ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1359279/Sir-James-Cable.html

- ↑ Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization page 1

- ↑ Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization page 1

- ↑ Jillson, Cal (2009). American Government: Political Development and Institutional Change p=439}}

- ↑ Ooi, Keat Gin, ed. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, From Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO pp=338–339

- ↑ Nixon Alone, by Ralph de Toledano, pp. 173–74

- ↑ Franklin, John K. (2006). The Hollow Pact: Pacific Security and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization. ProQuest. p=184

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20110426162320/http://www.cabinet.thaigov.go.th/eng/pm_his.htm

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=0lQ0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=YbkFAAAAIBAJ&pg=3661%2C2633318

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20140502004607/http://www.almc.army.mil/ALU_INTERNAT/CountryNotes/PACOM/THAILAND.pdf

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (India) 2000, p. 60

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20121007113024/http://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/SEATO

- ↑ US PSB, 1953 United States Psychological Studies Board (US PSB). (1953). US Psychological Strategy Based on Thailand, 14 September. Declassified Documents Reference System, 1994, 000556–000557, WH 120.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20121007113024/http://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/SEATO

- ↑ http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18430820 Nehru Has Alternative To SEATO. (5 August 1954). The Sydney Morning Herald (

- ↑ https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/seato

- ↑ Grenville, John; Wasserstein, Bernard, eds. (2001). The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts. p 366

- ↑ W. Brands, Jr., Henry (May 1987). "From ANZUS to SEATO: United States Strategic Policy towards Australia and New Zealand, 1952–1954". The International History Review. No. 2. 9: 250–270

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/vietnamfourameri0000unse p=46}}